Maitreyi Devi & La nuit bengali

Publié le 27 Mars 2018

My discovery of Maitreyi Devi happened, probably like so many outside of India, through Mircea Eliade’s novel which I read in French, La nuit Bengali, written in 1933 three years after this Romanian scholar, who later rose to become an influential ethnologist and specialist of the history of religions, had left Calcutta where he stayed at the home of an Indian professor (Surendranath Dasgupta). There, he had fallen in love with his elder daughter Maitreyi and, when their love was discovered, he was chased away from the house, never to come back. He remained for some time in India though, and genuinely interested in Sanskrit and Indian philosophy, spent some time at an ashram in the Himalayans before returning to Europe. It was there that he wrote the novel. It tells his story, his stay at the Sen (Dasgupta) household, from his arrival in India as an engineer in Bengal in the days of the Raj; it describes the originality of the young man who wishes to understand some of the “real India” which evades the anglo-Indians he meets in the expat circles. These are ferociously satirized as bigots and racists, and cannot for the world of them understand how one might contemplate any intercourse with the dirty “natives” (dirty on account of their skin colour).

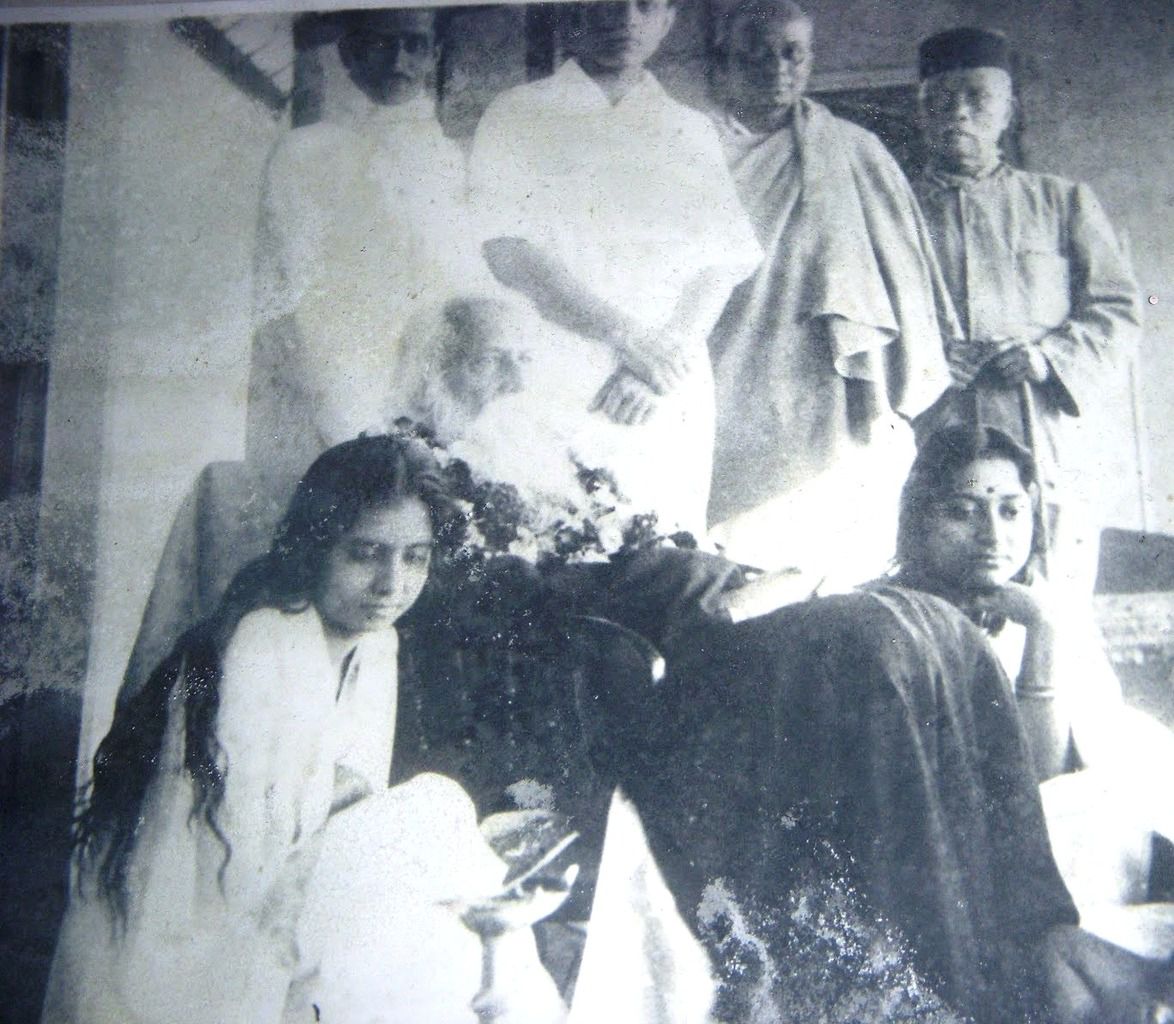

The young hero, who calls himself Allan in the book (he modifies his real name, but not the young girl’s) misconstrues the cultural intention of his stay in the Bengali household: he’s under the impression that if he’s invited to stay with the family, it could well be because the idea of his being a prospective son in law isn’t absurd. So when he falls in love with Maitreyi, the 16 year old beauty (though initially considered ugly) and prodigy of the family - she’s a poetess who’s attracted the attention of Rabindranath Tagore, Nobel prize for Literature, 1913 – he believes this bond might well materialize, in spite of denial stating the opposite coming from the girl. They could only be “brother and sister”…Nevertheless, she falls for him too, and, says Eliade’s version of the story, they go all the way, with Maitreyi visiting Allan at night in his room. Unfortunately they’re more and more suspected and spied on, and one day Chabu, Maitreyi’s little sister, sees them kiss and fondle, and tells their mother. The backlash is immediate as we have said.

Eliade’s novel isn’t without its qualities but also its ambiguities. Even when I was reading it, ignorant of the existence of Maitreyi Devi’s version of the story, I felt somewhat plunged into a romanticized and westernized fiction where many ingredients were present to titillate the reader: the strict parental background (I thought of Romeo & Juliet…), the rather unusual presence of this young Western boy in the intimacy of a Bengali home (this turned out to be historical), the blindness of the parents, and the naturalness with which sex appears in the proceedings (Ginu Kamani [here] writes: “the plot presented within, of seducing a sixteen-year-old Brahmin girl in her parents' house in Calcutta is ridiculously unlikely”). It’s self-indulgent and naïve, yet it also tells rather beautifully of a relationship which is never violent nor degrading (at least, to our 21st century eyes). With the Shakespearean romance still in mind, I ascribed its intensity to the strength of passion and thought that even if this was contextualized in 1930 Calcutta, it probably wasn’t the first time in reality or fiction that a well-educated young woman went to bed of her own accord with a “forbidden” foreigner who knew nothing of caste or family reputation based on marriage requisites he could not fathom. The novel ends in drama, which gave it a dose of realism and poetic justice, all of which reinforces the interest. Only later, when searching the net for other people’s opinions of the book did I realize it was at least partly autobiographical. One could even say it’s distanced from the real Mircea. Indeed, as Torsa Ghosal says here: “Alain [his frenchified name in the English 1993 version of Maitreyi’s book] is a device used by the author to distinguish his knowledge of India from the clichés of the Anglo-Indians: from the beginning, Eliade makes it clear that Alain has a limited understanding of the culture and the events he is recording.”

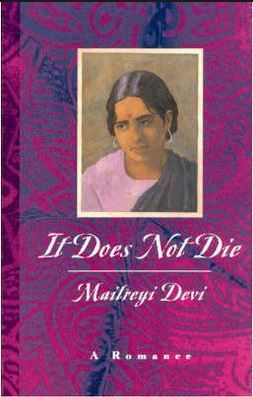

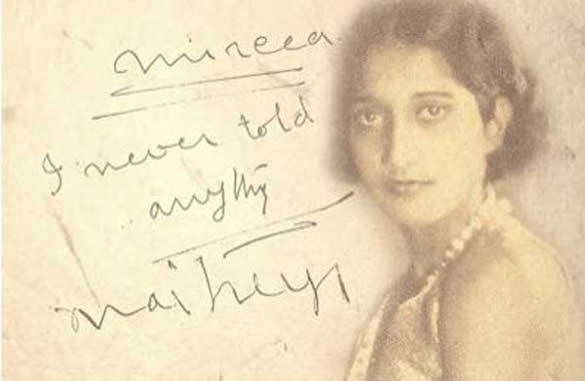

I then proceeded to read Devi’s story (Na Hanyate, translated It does not die, 1974), and here I stepped into a completely different world. First things first, the book was penned by her as a sort of pre-response to Eliade’s, because she had apparently only heard parts of his book read to her. She explains that she was shocked to hear that her former lover’s account contained elements of their story which she knew to be false, notably the night visits to him. She was also shaken that he’d used her real name, thus making it clear for any potential Bengali reader who the heroine was. But why did she wait for so long to write her account? Because in those pre-Internet days, things took time; time for Eliade’s book to spread outside Europe, then for readers to come to India, for the first person to mention the book to her (she says it was her father in 1938, p.175), for her to realize it contained material she accepted to rectify (she first shut herself up hearing the book contained “pornography”), and finally time to actually decide she was going to have to plunge back into a past she would have preferred to forget. As mentioned above, one learns a lot about the history of Maitreyi Devi’s reaction in this 1996 article “A terrible hurt - The Untold Story behind the Publishing of Maitreyi Devi” by Ginu Kamani, even though I believe she insists too much on Eliade’s guilt – an understandable position given Devi’s letters to Eliade’s translator. It is necessary to turn to Devi’s own version of the facts in order to really assess the “hurt” done..

The book is a dazzling maze of intertwined memories of her version of the love-story, her own life as a young girl then, with her poetic aspirations; her adult’s (and married woman’s) thoughts about the whole act of writing about the event after 42 years; the necessary inroads about her literary career, especially the links with Tagore, then the steps which led her to write; her first scandal-filled comments about Mircea Eliade’s book and the lies which (she says) have tainted her reputation, but then her softening as she realizes (or makes herself realize) how much she still loves him; her married life and her relationship with her husband, a generous, meek humanist she was obliged to marry but who proved to be a staunch support: all this goes forward, sort of, but also backwards, and the novel’s charm is that we are following a righteous woman who fights for her name and at the same time cannot accuse fully the person who she realizes wasn’t aware of everything Bengali people know about Bengal. Having Eliade’s version in mind, of course, adds enormously to the interest, since one is constantly comparing the two stories, and checking Devi’s choices and their realistic necessity. One knows she’s closer to the reality, because the very reason she’s writing is that she needs to state her “honesty”. And naturally she conveys a sense of the reality of 1930 Bengal in a much more forcible way.

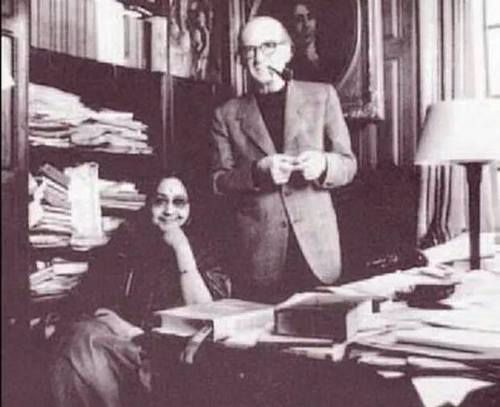

We come to know her very well, both as the young girl she hasn’t stopped being, who has magnified a boundless love for this brilliant young European, and as the lady who’s writing and feeling her way through the difficulties of understanding what has happened to her. I believe the passages where little by little, and then more and more, she suffers from a sense of timelessness, of reversal of time, of the domineering presence of past feelings she can still feel now and which overwhelm her with such heaving intensity, those passages are the greatest in the whole book. We see her losing her sense of self, of time, of right and wrong, as she spends days and nights crying, flooded by the surge of emotions which the renewed love brings inexplicably about; she goes through shame and guilt, through solitude and regrets, through loss and fear, and most of all she cannot hush the question: why? Why has all this happened to her? How will she ever be free once again? Who is this 23 year old boy, or ghost, who’s come back to visit her, a happily married mother and wife? She finally manages to open up to her husband, who amazingly enough, encourages her to meet Eliade and get some closure from it. She had several times tried to write to him, as she was passing through Paris (or other places), on literary calls and touristic visits, but this time she must go to Chicago where Eliade has secured a lecturer’s position. He had never answered, and she wonders why. Also, she has always been told he had sent her no letters after their separation in 1930: was this true? Only he could tell. She needs to confront him concerning the reasons why he wrote the lies in his book, she needs to see him as the tides need to come back to the shore, as day needs to follow night, and the branches that sway in the wind need to straighten themselves after its passage.

We also get to know the family, the beautiful mother who’s ever fearful of imposing herself in front of her formidably powerful husband, the renowned scholar respected by everyone. Devi describes her reverence for him, but also criticizes his overweening authority, and how he imposes his whims on the family, never wondering whether it’s humanly acceptable. Devi’s name is modified and so are other names, and I felt she was doing this just to prove to Eliade he could have done the same. So she’s Amrita (Ru in short), her sick sister’s Sabi and Mircea’s family name gets changed to Euclid…We get an insider’s understanding of the unconventionality of this Bengali family, unconventional because of the intellectual and artistic atmosphere in which everything is done: visits of important guests, references to well-known thinkers, the parental encouragement for the girl to meet and understand a lot of what’s going on in the city’s bustling artistic life…And so the unusual presence of the young student, brought in as a permanent guest loses some of its rarity, because he’s part of the overall initiation which the liberal but ideological father wants his daughter to benefit from. The two of them, in fact, “were two good exhibits in his museum” Devi writes.

Na hanyate carries with it the precious lyrical load of Maitreyi’s poetic vision: the book is filled with her transformed world, under the auspices of Tagore’s own reverberating universe. Everything she does, sees, feels, all the objects in her surroundings, the voices she hears, the creatures she comes in contact with, all this participates to the recreation of a world of beauty and is plunged into an infinite unity. Numerous allusions to her own works are present, but only by allusion, here and there a verse or the wafting strand of a song. Even though she is a city-dweller, she perceives plants, birds, night and day, stars and music with a poet’s acuteness and wonder. Everyday objects acquire an intensity which is given by her choice of words and her understanding of their importance. And of course her love takes its place in this whirling dance of symbols and references. When she has to stay in the mountains to be with her husband, who’s responsible for a quinine plantation (in Mungpo, where Tagore will come and visit her several times at the end of the thirties and where the “Rabibndra Bhavan” is set up, cf. in her book from p.168), she opens up to the new world of the forest, with its mysteries and silent voice, the incessant natural events which make it up: insects, flower, grass, wind, rains, etc. and it becomes a teaching of joy and peace.

Na Hanyate encapsulates a sort of mystic experience, that of a woman who’s painfully trying to express the meaning of what she’s gone through, not only when as a 16 year old adolescent she opened her flower to the rays of the sun-god of love, but even more in her mature age she’s trying to make sense of her life and what she has lived. I think the best I can do is quote from her writing:

“On sleepless nights, the fire of anger burns within me but with it burn my pride, prejudice, and all that I thought valuable so long. A taper of fear is coming up from within and is burning everything in its course. I am melting like a candle, and its light is spreading all over. Drop by drop the hard straight candle is slipping like liquid, melting my vanity, my sense of prestige. Everything is falling in that fire. My ego built through the prejudice of ages was unbending like that candle. But today the fire of fear has made it tender. Is out of fear? Am I afraid of scandal or disgrace? Am I suffering only for that? When at midnight, I stand watching the stars I realize it is not so. One who was growing larger behind the fear has destroyed it also. It is love, indestructible, deathless love. It is the fire of love that destroyed everything else and began to emanate light. The light entered into the depth of my being, in every corner of my heart, and all the blind alleys began to brighten up. All my pretensions, all my self-deceptions are evaporating, eroding; I am starting to see the full image of truth. My life is becoming meaningful in a new sense. I remember him, his half-forgotten face, his voice, his inscrutable ways, his anger, jealousy, and above all, his love. Gradually I am being lifted up into another dimension. It is another existence from where the good and bad, the truth and untruth, the fact and fantasy of this world appear meaningless. The shell of this outer world begins to peel off from me – mind says, praise or blame, all are the same – there are things truer than these.

I lay wondering why he destroyed this love, a gift of God. What did it matter if he had to go? If in ten years we would have exchanged even a single letter, that would have been enough. With that one letter, we would have bridged the oceans and continents of separation and could have become “ardhanariswar”. Our two selves could have acquired a completeness. But do Westerners understand all this? For them the fulfilment of love must be in bed. Yet he knew, certainly he did. I can see myself again in his arms, framed within a door. He is whispering, “Not your body, Amrita. I want to touch your soul.”

This is the truth, truly the truth. The body perishes, the soul is immortal. It cannot be killed by killing the body. Where is that body of mine? The bower of my youth? In this old decrepit body, my hair is greying and my face is lined, but the soul is the same, uncorroded by time.

None has succeeded in destroying it, neither my father nor Mircea; neither time, my own pride, nor the rich experiences of life. A feeling of immortality is entering in me – I am touching the infinite. “One who thinks, I am killing, or one who thinks, I am being killed – both do not know that no one kills or gets killed.” The truth that no scriptures could teach is becoming self-evident. Love is deathless. My soul, held by him in that Bhowanipur house, still remains so fixed. The infinite is flowing through the finite – the limitless is held in the limits of my body – I am far and I am also near, I am here and also not here.

I am an agnostic, maybe an atheist. But the change in me is shaking my disbelief. Let someone tell me, who I am, what I am. Where did the sixteen-year old bodiless self of mine exist so long?”(p.216-218)

One could easily decide that such a flow of thoughts is but the fictional rendering of frustrated love, that Devi is trying to give eternal, literary value to her incomplete youthful experience. To be able to refuse such an interpretation, you have to open the book, and immerse yourself in it. Its urgent plea is for a deepening of life to its invisible boundaries and unknown richness. The woman who is writing has gone through such an upheaval of all she used count dear and stable, social norms and traditions, psychological definitions, honest domestic wisdom, that the light she was granted has made everything but itself unnecessary. It is a religious experience, a revelation, of Love as Surpreme Power who, having once entered her soul, has thrust it upwards and away with it. And the fascinating fact is that this has happened not with the youthful experience of her 16 year old love, but with the mature transformation generated much later, as a tsunami crashing on her after its origin was foretold far, far away in the ocean.

Of course, the last part of the book, which tells of Maitreyi Devi’s arrival in Chicago and her final meeting with Mircea Eliade, is its climactic moment, its “revelation”. Like her, we both expect much of it and fear it: how much of the past can, and should, remain in the present? Isn’t youth but a preparation for life, and any forceful back-pedaling the sign of a narcissistic egoism? For those of you that haven’t yet read Na Hanyate, I’ll let you discover what it contains!

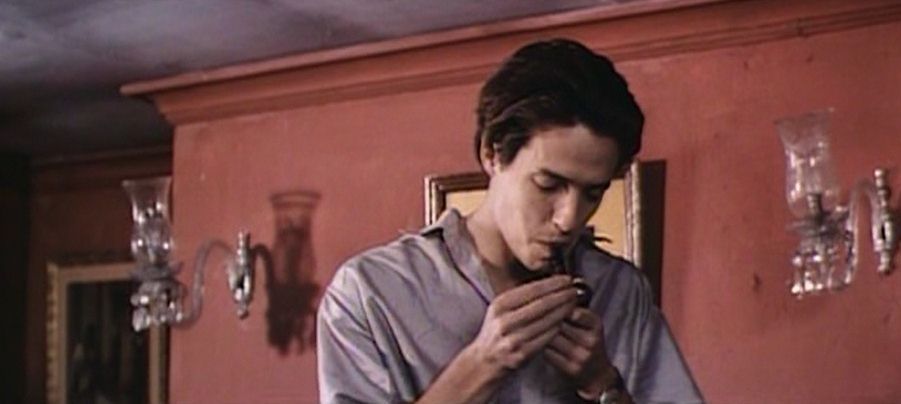

Eliade’s book has been shot in 1987 by a French film-maker who secured Eliade’s wife’s consent to do so, and in so doing incurred Devi’s wrath, because she had asked Eliade in Chicago not to authorize any translation in English while she was alive. So she saw the film as a breach of his promise (see G. Kamani’s article). The Bengali night (1988) is in English, and even though it simplifies Eliade’s novel at some extent, which is natural for any film screening a novel, I believe it possesses a true worth, first for its very pleasant allusiveness (though I really think it mustn’t be so easy to follow if you haven’t read the book), and its decision to transpose the story in modern-day (well, 1987!) Calcutta. It isn’t a “historical” film, which one can regret, but it certainly gives it a welcome freshness. Any raunchy titbits are expunged, too. On the other hand, I can’t say I liked very much Hugh Grant’s personification of Mircea, and Supriya Pathak’s world of emotions seemed very limited, owing perhaps to the cinematographic constraints. Shabana Azmi has the role of the mother, but she’s rather underused, and doctor Sen (Dasgupta) is played rather aptly, though conventionally by Soumitra Chatterjee, and if one knows how much any film-maker can draw from him, he’s also very much wasted. I also read that SJ Bhansali’s Hum dil de chuke sanam’s story is modelled on Na Hatanye’s story… No comment there.

For those interested, here’s a video of Mircea Eliade’s life and works: Video of Mircea Eliade’s life, and his Wikipedia page, containing a lot of information. And the philosophical-oriented among us will appreciate Dr Sriparna Basu in-depth analysis here. Her contention, which is brilliant but partly debatable as regards the 1930 period, is that Eliade’s coming to India has come to represent for him an encounter not with the historical, but meta-historical, “eternal India”. It’s the typical orientalist attraction which is once again at work. This is what she writes: “It is not Maitreyi's father who disrupts the relationship between Maitreyi and Alain/Eliade, but rather Maitreyi who disrupts the relationship between the two men. Even though in terms of historical event Dasgupta expelled Eliade from the household and ended his affiliation with the University of Calcutta following the discovery of his affair with Maitreyi, Eliade holds Maitreyi rather than Dasgupta responsible for his departure from India: "Because of M. I lost the right to become an integral part of 'historical' India”.

I think Sriparna Basu does a good job on Eliade’s narrative, even if she probably judges it too hastily in the context of its writer’s later elaborations. It was, after all, written when Eliade was only 25. The reintegration of his Indian “gesture” as part of a greater frame belongs, I feel, to his later period. But I don’t really think she has gotten to the roots of Na Hanyate. She tries to apply to it the nationalistic grid of interpretation, and sees Devi contradicting herself even when she invokes Tagore and Gandhi as her inspirers. Basu uses the unvisualizable figure of Caliban (the monster from Shakespeare’s The tempest) and applies it to inscrutable narrative figures to account for Devi’s inexplicable rendering of her own fictional character. I think this is a very far-fetched explanatory model:

“Through a displacement of the patriarchal authorities which constitute her self and define the discourses and idioms in which she speaks, Amrita's text seeks to articulate a sense of women's agency, albeit complex, problematic and shot through with contradictions. If we are to regard Na Hanyate as analogous to Caliban's text, it is clear then no uniform subjectivities or teleologies of resistance may be read into it. As it stands, Caliban's entry into language cannot promise us a complete transparency of communication nor a complete displacement of available ideologies that have made Caliban's enunciation possible. What emerges, instead, is a multiplicity of voices, not necessarily consistent with each other, but effecting an estrangement of the signs of dominant discourse. Amrita's rewriting of the dominant tropes of "truth" and "fidelity" suggest it is possible to reinflect and appropriate the signs of dominant discourses to assert a complex sense of agency and empowerment. Very importantly, Caliban is available here as a witness to her construction, and shows up the contingency of signs through which it is effected.” (n°41 of her article)

Basu partly misses the point of Devi’s book, which is to explore the psychological, spiritual and religious realities which her erotic/amorous encounter has triggered. She’s right to insist on the political aspects because certainly Devi looks upon Eliade’s arrival in her life in the light of orientalist/colonialist lines. She brands Amrita and Devi for sounding a “manic voice” (n°40), but she doesn’t hear that such a voice is that of a lover whose eyes have been opened to a world so many times greater and wider than our own that it cannot but occasionally lash out at its limitations.

Other reviews and opinions can be read here and here. And there’s a video with an interview of her sister.

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)

/image%2F1489169%2F20180327%2Fob_1f3083_la-nuit-bengali-1.jpg)

/image%2F1489169%2F20180327%2Fob_01c82f_la-nuit-bengali.jpg)

/image%2F1489169%2F20180327%2Fob_ed845d_9780226204192.jpg)

/image%2F1489169%2F20180327%2Fob_125c2d_1667153.jpg)