Paromitar ek din: can women stay the forces of lunacy?

Publié le 3 Juin 2012

I have only recently been made aware of the interest of movies by and with Aparna Sen, having seen Baksha Badal recently (check Sharmi’s take on it), and so here’s a look at a pleasantly intimate story, shot by the Bengali director in 2000. The film’s a flashback, we start in the courtyard of Shanaka’s house, a rather wealthy Calcutta lady, who’s just passed away and where friends and relatives assemble to pay their last respects. Among them is a startlingly elegant, bespectacled young woman called Paromitar (Rituparna Sengupta) in a white sari and holding her attaché on her knees. Her look is vacant, when she’s offered drinks or food, she jumps as if disturbed from a reverie and we soon learn she’s pregnant because at one stage she goes to the bathroom and vomits.

She knows the house very well, because she once was its housewife. But she’s now divorced from her husband Biru, and the deceased lady was the mother in law (that’s Aparna Sen herself) she’d lived with for a few years. And so the movie goes back and forth between this courtyard scene and the life he spent in this house. It all starts with her wedding; her mother in law marvels at her new daughter in law, and we discover the family where Paromitar now belongs to – a dimwitted sister, Khuku, whose mind hasn’t evolved beyond girl-age (her brother says she’s schizophrenic– but he clearly doesn’t know what the word means), two older brothers, the father whose presence is rather in the background, critical and intolerant, and an old gentleman, Mina (Soumitra Chatterjee), apparently Shanaka’s slightly senile (or at least strangely fragile and self-pitying) former suitor, who is allowed to come around and sit in the deserted drawing-room.

Then there’s Shanaka herself. Aparna Sen cuts a fine figure there: her Shanaka, formidable and fragile, her speech made funny by the paan she’s constantly chewing, now an old hag and now a cheeky seducer: she’s a free woman who doesn’t mind flying kites on the roof with her little nephew and giving Mina some pocket money saying he’ll repay her in a future life. The way she looks at him, you don’t know what game she’s playing exactly. Anyway, Shanaka, free as she is, is also trapped, and when Paromitar enters her life, it’s a breath of fresh air. She quickly befriends her as her daughter, and they become a spirited pair, leading almost a lovers’ life, discovering the pleasure of pleasing the other and not caring about what the rest of the household thinks or doesn’t think.

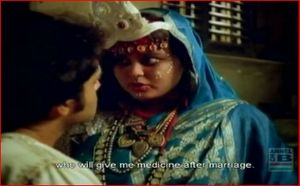

Paromitar has given birth to a cute little boy, but he’s spastic, and this brings her close to Shanaka and her infantile and infortunate Khuku. Shanaka suffers from this constant reduction of her world, between dumb men and her tiringly mental daughter. Her solitary needs meet Paromitar’s, also hurt by her husband’s rejection of her child and herself as his mother. Biru can’t see that he’s perhaps the biological source for his son’s handicap. Khuku and Bablu, figures of innocence, serve as reminders that the human community finds meaning only when it defines itself by integrating its fringe members as well as the “normal” ones. The film which is shown in the handicapped centre (and which certain people find too long) serves this purpose. One scene where Khuku is dressed up as a crazy bride and asks her brother why she cannot be a bride too, I found heartbreaking:

Khuku is a powerful symbol in the movie, because her outlook on other members of the household is without any of the normal precautions which all such micro-societies set up in order to make life liveable. The director makes her into a repository of innocence and artistic beauty (she’s a gifted musician) which becomes a reference against which the other members of the household are compared to. When Bablu is born, his added presence to the level of abnormality of the house is too much, and Shanaka’s son’s family (they had been occupying a wing of the house) leaves, frightened by the possible concentration. Biru is rarely there, and Shanaka’s husband dies. So the two mothers remain with the two retarded children.

It is therefore quite normal that when Paromitar tells Shanaka she’s found another partner, Rajiv, and divorcing Biru, that a shocked Shanaka tells her she’s being shameless and pleads her to stay. Her newfound balance is shattered: she is now left in this ancient dilapidated house with no one but Khuku and the old suitor, Mina, both too unsettling and alienating for her to bear very long. The film soon focuses on her last moments, and she logically dies a victim to the destructive forces of solitude and lunacy.

House of memories (the English title) therefore explores the rarely dealt with subject of women and idiocy or infantilism: contrary to men, women seem to adopt a more caring and understanding attitude, but which can suffer from a certain sacrifice (or sinking) of their identity. Paromitar’s arrival in Shanaka’s life testifies to the older woman’s need for normalcy: her emotional balance is affected by the low level of psychological exchanges; yet she has adapted to it, and when Paromitar leaves, she’s unable to return to that low level, and (it seems) lets herself die. Paromitar’s stare (sitting in the courtyard) can be interpreted as her realization that what Shanaka has gone through might well be threatening her too, for all the forces of life and joy that seem to sustain her at the stage she’s reached; she might also be meditating on women’s plight in general: do they have a role (a role different from men’s?) in the sharing of responsibility as to whether society should accept a certain level of unsuited individuals like Khuku and Bablu? Can art, poetry (Paromitar writes beautiful poems which Mina praises her for) or the cinema help them to fulfil what they might see as their mission?

There is an interesting take on the film here: filmimpressions

And you can watch it on YouTube

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)