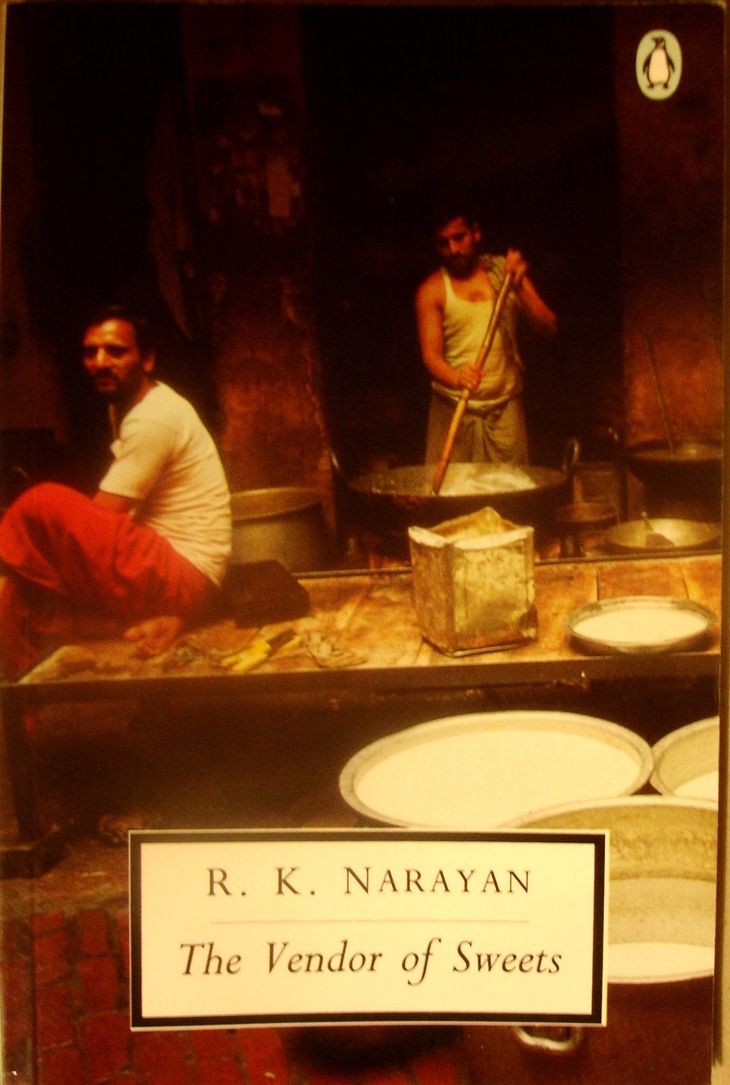

The vendor of sweets

Publié le 18 Octobre 2009

R.K. Narayan’s short novel The vendor of sweets (1967) is the story of a wise man, called Jagan, who lives in the narayanian town of Malgudi and prospers by selling quality sweetmeats appreciated because they aren’t overpriced or watered down with cheap ingredients. He’s a believer in honest practises, and a living proof that free enterprise when practised within the rules not only brings money and satisfaction to its initiator, but also satisfaction and development in a community. At a certain level of entrepreneurship and provided the adequate circuits of supply and demand are long-lasting enough to enable investment to pay off, people can flourish and their individual interests coincide with those of the group. This economic introduction might seem a little out of place, but in fact R.K.Narayan’s novel touches the themes of individual and collective satisfaction, and Jagan’s shop, which employs five or so people and caters to people’s pleasurable needs if not nourishment, is typically a small viable firm with a social and human mission: that which demonstrates that work values bring about peace and a sense of togetherness, which larger companies, where financial realities are sometimes of more important than people, always risk dehumanisation instead of civilisation.

This social dimension is perhaps best represented through the character of the “cousin”, who acts as Jagan’s confident and counsellor throughout the story. He isn’t family really, but he comes to the shop every afternoon and after having taken his bite of the sweets in the kitchen at the back (something which Jagan doesn’t mind at all, and even if he notices it, lets him do it, out of pure generosity), comes out front and sits next to Jagan to chat and listen to him. From a certain perspective, he is the quintessential parasite, but precisely, because Jagan’s shop is based on honesty and sound practises, where there is no selfishness, there are surpluses, and the cousin, along with the cooks and a few other people, benefit from them. Besides, the cousin has an invaluable service to give, which is well worth his daily pilfering. He listens to Jagan, he understands him and really puts himself at his disposal for anything he might need. This is a disinterested service which certainly comes from his good nature, but also from Jagan’s benevolence: you are open-handed, I’ll be open-eared.

Now the salesman is a widower, who has been left with an only son, Mali. And the problem is that Jagan isn’t an educator; he’s hesitant and weak-willed; he’s an admirer of his son’s intelligence and originality, or what seems so first. So when his son decides he’s had enough of his schooling, he takes it for a form of self-sufficiency; when Mali decides he wants to become a writer (he will say later he cannot imagine himself as a vendor of sweets!), Jagan bows at so much talent, and when Mali steals his money to pay for his trip to the US, where he will learn the writer’s trade (having spent a year doing nothing), the father convinces himself that this is a sign of commendable enterprising spirit. Finally, Mali decides to start a business, based not on the sale of his stories, but of a story-writing machine (of all ideas!) It is only then that Jagan finds it hard to swallow. Mali is Jagan’s opposite, almost. He could easily be read as new India going modern and technological (which cannot be done without a certain amount of moral cynicism), whereas Jagan, a staunch Gandhian, stands for traditional India and its insistence on autonomy and self-reliance. But there is more: Mali openly criticises the culture of his native land; for him, India is wrong, and because it has been wrong so long, it cannot adapt other than by force. Mali doesn’t believe in talking people into change, he doesn’t believe in listening to people’s needs. This story-machine of his is thrust upon the public without even making a survey as to whether or not it can be in demand.

There is a symbolical image here, that of writing a story. Mali first wanted to be a writer; this is what made him want to quit the old educational system. He told his uncomprehending father, at that stage, that what he would be writing was nothing like what his father could imagine. But he wrote nothing. Then, after having gone to learn about writing in America, he comes back with a business idea: to sell story-writing machines in which would-be writers would only have to enter the number of pages, the number of characters, the place and time, the type of atmosphere, etc. and the machines would churn the story for them! For Jagan, who spends his vendor’s time reading the Bhagavad-Gita (1), and who had first applauded his son’s literary pursuits, this is impossible to understand. In fact, Mali is trying to market the most unmarketable thing: inspiration, man’s spirit. He doesn’t choose to sell art, which would be parasitic enough, perhaps, but the source of art. His business would, if it succeeded (but the book doesn’t say he fails), drown people’s imagination with preformatted productions which could be reproduced mechanically given the right ingredients. As opposed to the cousin’s idleness, which is in reality deeply needed, because it provides meaning and communal companionship, his business talents would develop only individual barrenness. Instead of the sensible creativity of true listening and down to earth story-telling, his mechanized stories would replace doorstep chatting and neighbourly exchange by hypnotised and repetitive reading habits. I don’t know if Narayan was aiming at any precise targets, but today his message rings like a warning that was well ahead of its time, especially concerning some Bollywood productions.

Miles away from the parasitic consumer society that is plaguing not only India but the whole developed world, Jagan’s character is a reminder of the possibility of detachment and simplicity, which even he has had to learn: the book shows him first fighting against his son’s encroaching possessiveness. When Mali had first decided that his father (along with his father’s money) would agree, as always, to pay for his selfish plans, he had not counted on a limit: that of Jagan’s self-respect. Putting his father’s name on that advertising leaflet in order to force him into business and make him pay was one step too many, and Jagan’s reaction, perhaps childish in a way, is quite normal. He shuts himself up like a hermit crab, and avoids confrontation. Not very mature, definitely, but what Mali is doing is not mature at all. In fact what Jagan will need, like Rama in the Gita (who, says Narayan, prods the hero on when he is in doubt), in order to understand what to do next, is a divine intervention. Let's see which one!

Having childishly reduced the price of his sweets in the hope this would discourage his son from asking him for money, he incurs the wrath of sweet-selling competitors, who soon flock in to bring him back to economic reason. And with them comes a stranger, a sort of sage who lives in a nearby garden. He’s a sculptor of statues, Godheads, and he asks Jagan to come and visit his garden. The climax of this visit occurs when he asks Jagan for help to lift out of the water a stone out of which a god will later have to be carved. Jagan is afraid that this sculptor might be a stooge acting on behalf of the dispossessed rival merchants, and that he might be drowned by him, suppressed as a disturbing competitor. But nothing happens, and this ordeal creates the shock which Jagan needed. At the end of the book, he leaves his house, and holding on to nothing but Gandhi’s example and his back-door key, which he asks the cousin to give to Mali, because the shop and everything he has will belong to him one day. He has won the final victory not over Mali but over himself and his comfortable and virtuous life that still held him prisoner. His new janma (life-stage) can begin. He joins the sage in his sculpture garden.

One could look upon Narayan’s story as a vindication for the need of India to open up and attain political and economical adulthood. Today in 2009, this is a plea which has been heard, after all. When Mali comes back to the motherland and confronts his cranky old father who is looking back towards the past, whereas the boy, with his young Korean girlfriend (not even his wife) impatiently waits for him to pull India out of its dustiness… One might sympathize. The young lady, called Grace, is charming, she does charm Jagan (who isn’t very hard to charm anyway), and she represents perhaps the essence of a civilisation freed of nationalistic shackles. For Jagan of course, all this modernity is just flouting the principles and the order that he not only believes in, but for which he has fought and gone to prison for (because of his connections with the Satyagraha movement). How can the two understand one another? And in fact Narayan’s answer will be: there will be no understanding, but thanks to old India’s principles of resilient spirit of tolerance and open-mindedness, the old will let the young have their way, and try their walk of life. After all, even the old don’t always understand the young, they are still their sons and fellow human-beings.

I suggest an interesting review by Frederick Glaysher here.

(1) Gandhi wrote of the Bhagavad Gita, in a tone that would certainly apply to Jagan: “The Bhagavad-Gita calls on humanity to dedicate body, mind and soul to pure duty and not to become mental voluptuaries at the mercy of random desires and undisciplined impulses.” (link)

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)