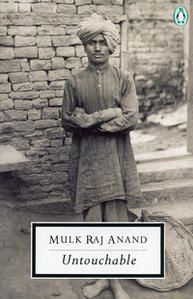

Untouchable

Publié le 30 Janvier 2008

Mulk Raj Anand’s small fiction volume « Untouchable », which dates back to 1935, evokes the life of a young sweeper called Bakha, through the description of a day’s happenings, from the morning when, only half awake, and after a cold night (due to his love of British clothes, he despises ordinary sleeping rags), he has to rush to clean the latrines before anybody can use them, down to the evening throng that he joins in the nearby city, where a rally in support of Gandhi has been organised. In between, we follow him and his thoughts, and we are made to understand the joys and frustrations of his dalit condition. Joys, because he is a young and strong lad, whose lively and gentle nature has predisposed to the pleasures of contemplation, dreaminess, and wholesome physical exertion. But also frustration and violence, because as an untouchable, this generous human being is denied a normal social condition.

Mulk Raj Anand’s small fiction volume « Untouchable », which dates back to 1935, evokes the life of a young sweeper called Bakha, through the description of a day’s happenings, from the morning when, only half awake, and after a cold night (due to his love of British clothes, he despises ordinary sleeping rags), he has to rush to clean the latrines before anybody can use them, down to the evening throng that he joins in the nearby city, where a rally in support of Gandhi has been organised. In between, we follow him and his thoughts, and we are made to understand the joys and frustrations of his dalit condition. Joys, because he is a young and strong lad, whose lively and gentle nature has predisposed to the pleasures of contemplation, dreaminess, and wholesome physical exertion. But also frustration and violence, because as an untouchable, this generous human being is denied a normal social condition.

The book is not without its defects. For example it starts dealing with characters that we don’t meet later, and seem forgotten; it contains narrative styles which don’t really coalesce; and what happens to the hero is perhaps not as dramatic, given the intensity of the subject, its political and anthropological importance. But one feels interested in him; one imagines his life very easily. Bakha has a clear, individualised identity, a voice too, a soul: good characterisation. His peaceful nature is charmingly present, his angers and sorrows are painfully graphic, and Anand’s voluble and graceful style grabs you from the opening, all the way to the last section, the Gandhi rally, where somehow he loses you because of his desire to make us hear ideologists debating Indian democracy. Still, the bulk of the story centres around Bakha, and that is what I’ve been interested in.

Anand was obviously confronted to the difficulty of a task that had not been tried a lot before him. How can one make people understand that an untouchable in Indian society is not only a human being like all others, but that the whole structure of Indian society, and the whole notion of segregating human beings, is standing on end? Such a small book (156 pages) indicates that either the challenge was too great for Anand, or that he hasn’t comprehended the full possibility of the literary task. So, as one starts reading the thin volume, one expects an explosion of denunciation and exposure that simply isn’t there. For all its good intentions, Untouchable is in fact a stepping-stone for greater works that will need it to jump deeper into the issue. Perhaps it wasn’t possible to go much further in 1935.

Anand was obviously confronted to the difficulty of a task that had not been tried a lot before him. How can one make people understand that an untouchable in Indian society is not only a human being like all others, but that the whole structure of Indian society, and the whole notion of segregating human beings, is standing on end? Such a small book (156 pages) indicates that either the challenge was too great for Anand, or that he hasn’t comprehended the full possibility of the literary task. So, as one starts reading the thin volume, one expects an explosion of denunciation and exposure that simply isn’t there. For all its good intentions, Untouchable is in fact a stepping-stone for greater works that will need it to jump deeper into the issue. Perhaps it wasn’t possible to go much further in 1935.

What I particularly appreciated is the description of the colonial situation in which we are plunged: Bakha is ironically trying to escape the alienation of his Indian condition through mimicry of the British model. He yearns after the British soldiers’ clothes, one of their hats, their style, their language which he wants so much to learn, that hockey stick which an “amazingly kind gentreman” has presented to him… In fact, Britishness is for him the way out of untouchability: not quite Gandhi’s message. That colonialism is thus (half) vindicated through a denunciation of untouchability is one of the novel’s peculiar (but no doubt historically sound) paradoxes. Perhaps for Anand, who lived in England for a long part of his life, the English version of civilisation was preferable to the Indian caste system?

Nevertheless, the story’s main interest remains the insider’s sympathy for Bakha. It isn’t enough to say that through him, the author has evoked humanity, beauty, and grace. He does that, because his young hero is so delicately portrayed, and the funny or touching anecdotes which fill his day are so humoristically connected with the more dramatic episodes. There is a very successful emotional combination of frightening and pleasing events. But through Bakha, we also see India, its splendour, its evocative mystery, and, I am tempted to say, its femininity. The rolling landscapes, the soft evening breezes, the childhood memories, even the people, in spite of their prejudices, are forgivable because they are poor and uneducated. All this simplicity, even if it can hurt, because it is unrefined, strikes as far less scathing than other portrayals, in later, more mature books.

One is sometimes reminded of Shylock, in Shakespeare’s The merchant of Venice. Like him, Bakha is wounded in his flesh by a pollution that he cannot accept, and that he painfully has to learn to live with. Like Shylock, he could say: “Am I not human?” to all those who shout at him and treat him worse than a dog. There is a very moving scene, when Bakha brings a child to her mother, a child that has been wounded in the head by a stick during a hockey game. Before the game, he had in fact noticed that the little one wanted to join in, but the other players wouldn’t let him. And so after the (rather serious) incident, when Bakha alone takes him to his mother, fearing for him, and worried about the others’ carelessness and insensitivity, the mother grabs the child from him, and she abuses him for having “touched” it, and probably she thinks, hurt him. His love of defenceless innocence becomes a cause for shame and insult.

Anand’s call for a society where castes would no longer inflict pain on one another gains strength when we realize that Bakha’s ideas are brainstormed into submitting and justifying his own lowliness. It will not be more toilet flushes in India which will solve the problem, as E.M. Forster seems to believe, in his Introduction to the novel. Even Gandhi has been powerless to eradicate the problem. The scourge goes much deeper, to levels of animality which reside within humanity, and which some men can unfortunately convince other men to accept as their primary nature. Man is both angel and beast, and some beastly men, who need slaves to exert their greed and thirst for cruelty, and who can’t bring other beasts to cringe before them, use the angels. That is the drama of untouchability. The grace of the human body, the wonder of God’s creative powers is transformed into a poisonous spell or leprosy that disfigures it. Untouchability might seem animal-like in its deformation of human dignity, but it is fact very human. It is the animal or beastly side of humanity that expresses itself there. Anand evokes this drama, this plague of our condition, but it will take many more powerful writers, thinkers and politicians to fully denounce its essential scandal. It will take many more civilisations to change not beast into angel, but man into man.

PS: an interesting take on the book, and a description of today's dalit situation here (thanks Banno). Here's an extract:

The book was written in 1935, but is life for the untouchables any different now? It’s obvious not, check out for yourself here.

Yes, a lot of the Dalit women can fill water from a tap now, and don’t have to wait around a well, hoping for a sympathetic upper caste person to turn up to fill their pots, like Bakha’s sister had to. But like Bakha’s sister Sohini who is mauled by the priest, the Dalit girls today too regularly have to face the threat of rape if they show the smallest signs of raising their heads.

A lot of people can get an education, unlike Bakha who even though he is willing to pay one anna per lesson to the little upper caste boy who plays hockey with them, has to beg to be taught with humility. A lot of people can get other jobs, and don’t have to continue sweeping and scavenging like Bakha, whose life revolves around the latrines. So, yes, perhaps things have changed a little. But how much?

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)