The white tiger

Publié le 2 Janvier 2010

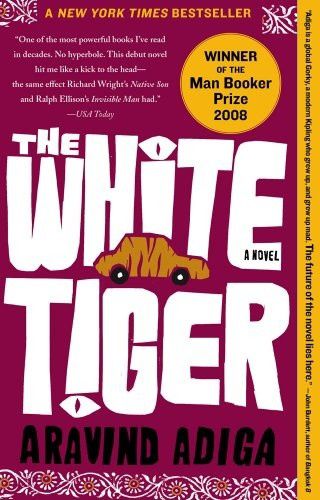

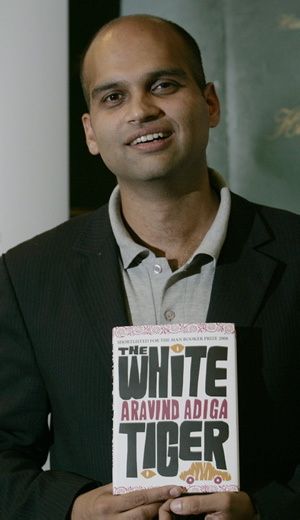

The white tiger is a rare genetic variation of the normally ochre-skinned feline that is both feared and respected as the king of animals in Asia. But it’s also a 2008 novel by Aravind Adiga which the press has acclaimed and which I’ve just finished reading. Somebody (The publishers weekly) said about it that it was “the perfect antidote to lyrical India”. Other books and films could claim that title, but it’s true that there is, especially in the West, a tendency to lyricize India, matlab, to romanticize it by raving about the colourful and exotic surface, and ignoring the harsher reality below. I’m sure I myself have been a blind victim to this illusion.

Well thanks to guys like Adiga (I would also like to mention writers like Rohinton Misty or Khaled Hosseini, who even if he’s an Afghani, depicts a society shown from the ground roots, which has much in common with Adiga’s. And let’s not forget earlier film-makers like Shyam Benegal), my eyes have opened, and it isn’t that I’ve forgotten about the more colourful iced top, but the cake has definitely acquired a richer and sourer taste. Quite normal, obviously. What Arvind Adiga has done is create a style, a voice and an urgency which all together compel to read and please the reader. And he has something to say. But first the style, the voice.

Balram Halwai, the main protagonist, is writing to Mr. Jiabao, China’s Prime Minister, but in reality, I am Mr. Jiabao, you are, we all are. Balram is telling us how India is now ready for companies from China to come and invest there, because newly set up entrepreneurs have cleared the way for them. People like himself, in fact! And we’re going to to see what it takes for India to become a land of opportunity and success stories to unfold. For those who know what violence is simmering under the silk chunnis and colourful saris, his portrayal of contemporary India will not come as a surprise, but others will shudder.

For Balram the underdog barks very well, and that’s his first asset. It’s very hard not to listen to him. Only masters can do that, by the way. Only masters can make sure that people listen to what they say without being interrupted. Balram is a sly guy too: he is really a master, and at the same time he makes you pity him, he takes the pitiful mien of the pauper, the village peasant boy. Well, in fact it’s sometimes that voice we hear, sometimes the other one, the entrepreneur’s voice. But he does that because he has a secret to share.

He’s clever, because he tells us that secret from the start: he’s killed his master, and he’s become a master himself, says he. But we don’t believe him, because he’s shut up in a room somewhere, and he’s busy dissecting a “wanted” poster where his name and particulars appear. It sounds like bravado, and somehow we fear that all this is going to end up badly, that he’s in a mess and they’ll catch him. Well, they don’t. Not only that, but he’s caught them for once. Incredible, but he’s made it. He’s actually gotten away with it, and the whole book tells Mr. Jiabao how he did it, starting from his childhood in the village and ending in that office full of chandeliers in Bengalore. Whew.

The first trick was that his father, a consumptive rickshaw-puller, wanted him to go to school and learn how to read and write. Detail? No, it’s the heart of the matter. He didn’t lack pluck and good fortune after that, but that was the essential move. The book makes it clear that education sets you apart in a way we have no idea in the West, where every youngster is crammed full of knowledge he doesn’t even know he’s knowledgeable about. Over there, if you can read, you can become a driver, you can be sent to the big city, and be noticed by the right people, be hired, and then move on little by little by edging those who can’t read or write.

And so Balram ends up replacing the older driver he’s ousted and driving the master and mistress in Delhi. He doesn’t quite understand what shady business they’re up to at first, but it certainly isn’t fair dealing, given the amounts of money in transaction that he sees while driving their carriers between banks and posh hotels. He gets to know the drivers’ gang, who slowly initiate him to ways by which he might be able to trick his master, and we of course start seeing the connection. What’s he going to do? Where does the murder fit in?

The hitch is that his master, M. Ashok, is a kind guy. Yes, incredible, he’s even his defender. For all the other rich, mobile touting passengers, Balram is barely a human being, he’s a slave at best, and sometimes hardly more than an animal. But M. Ashok is always there to vindicate him, and underline his basic loyalty, his honesty, his serviceability. When Balram is tempted to tell him his grievances, he suspects he wants a raise, and hands him money without hesitation. How on earth do you get rid of such a considerate master? And most of all, why would you want to get rid of him? Having been brought out of your village, into the capital, being paid handsomely (true, he normally has to send the money to his family, but well…), and being looked after by a humane master, what more on earth would you need? Wouldn’t any underdog believe he’s won his life’s worth of satisfaction?

Now you would only believe that (suggests Adiga) if you don’t know you’re a slave, if your father hasn’t sent you to school, where poetry has opened your mind to beauty, because, as the great Iqbal said “the moment you recognize what is beautiful in this world, you stop being a slave” (p. 236). You might have been brought out of the “Darkness” of your innocent village, out of the darkness of poverty (1) that of ageless ignorance and repetitiveness, into the “Light” of the city, where modernity rages with all its splendour and violence, you are still a slave, a nobody. As long as your master has a right of life and death on you, what are you? Because that is the case for Balram, no matter how kind Mr. Ashok is. He belongs to a caste of thugs and profiteers who will forever be crushing people like drivers and servants. These are sub-humans who down deep, are expendable. Just like that cyclist whom Balram’s mistress hits and kills while driving the car, completely drunk, one night. Because of his considerate ways, Mr. Ashok is a sort of exception, but only a sort. He would never think of Balram as a potential equal in terms of humanity. Balram for him is not much more than a good dog.

At this point we have to introduce a particular theme which is half-bakedness. That’s what Balram calls himself, half-baked. The schooling he’s got is unfinished. He’s only half-baked, but also already half-baked, mind you. Some are completely raw. He has something missing, but something the others lack. He’s an intermediate product, and that accounts for his need to constantly feed on sources of information in order to become more complete and understand life better. This half-bakedness has probably protected him as much it has “buggered” him. It is as much a matter of luck as of progress; and if he’s regretting it in part, he’s made the most of it. He’s not formatted as some Indians have been, through history, to the point that they have adapted too much to the role-models they were aspiring to, and as a result, have changed nothing in the society. They fitted, so why should they? Balram, still half-raw from his village and from the pain of his ancestors, and having been given some means of escaping, escapes. But he’s not been shaped into climbing the ladder the civilised way!

Another fantastic image Balram comes up with is that of the Rooster coop:

“The great Indian Rooster coop. Do you have something like it in China too? I doubt it, Mr Jiabao. Or you wouldn’t need the communist party to shoot people and a secret police to raid their houses at night and put them in jail like I’ve heard you have over there. Here in India we have no dictatorship. No secret police.

That’s because we have the coop.

Never before in history have so few owed so much to so many, Mr. Jiabao. A handful of men in this country have trained the remaining 99.9 percent – as strong, as talented, as intelligent in every way – to exist in perpetual servitude; a servitude so strong that you can put the key of his emancipation in a man’s hands and he will throw it back at you with a curse.” (p. 149)

He then gives the answers to the two questions: “Why does the rooster coop work? How does it trap so many millions of men and women so effectively?” and “can a man break out from the coop?” Here are the answers:

“the Indian family is the reason why we are trapped and tied to the coop, and if a man wants to break free, it means he is prepared to have every single member of his (always very large) family “destroyed, hunted down, and burned alive by the masters. That would take no normal human being, but a freak, a pervert of nature.

It would, in fact, take a white tiger. You are listening to the story of a social entrepreneur, sir.” (p.150)

Ooo… This is big stuff. If any political party, any intellectual, any social reformer starts touching to the sanctity of the Indian family, he’s in for big and lasting trouble. Balram doesn’t want any harm to his family, of course. He’s as trapped as all the others. He’s just a chicken in the coop, and he knows very well that his neck can be wrung any day, for any reason. But, he also knows that everybody has a neck, masters included. He’s away from the immediate contact and pressure of his family, and afraid to fall into its trap (they want him to marry, to become even more tied up in the coop). Balram cannot forget the freedom he’s already tasted, that’s the rub. He’s been allowed to savour that taste, and it cannot be shaken off. He watches everyone playing a role in and around the coop, but he knows that there must be a way out of it for him.

Balram’s story is that of a man who has become immune to the strange mimetic dream that locks up his fellow sufferers inside the coop. He’s in it too, but to him, it feels like a prison, whereas for them it is the normal state of affairs, and if they become chief rooster in the coop, they have succeeded in life. They are under a spell. That spell makes them believe it is their master alone who could free them from slavery: if they recognize their slavish condition, they have no other hope than look to him for their well-being. So they treat their masters well, and this way they will be well treated. The same sense of total loyalty inhabited those who believed in the meaning of the king before the French Revolution. The idea that the king was bad was normal: that was part of the frame. The king was the top peg that held society together. But some blasphemers spoke about getting rid of him, worse, beheading him! For those conservatives, the very fabric of reality was based on a hierarchy, not on equality. Thus the revolutionaries were seen as nihilists, because their opponents couldn’t imagine what reality would be like in a situation for which there was no reference any more, and which would force people to live on their own private resources (the sacred font of power having disappeared), and their conscience full of a heinous crime.

That is exactly what Balram will face up to. OK, you know he does kill his master, and I won’t tell you how it happens to preserve some suspense, but the sense of freedom that he feels after that is also a sense of transgression, that almost nobody before him has expressed so clearly, because of the age-long submission of the slave to the master, of the poor to the rich. On his own, he has guillotined the king! He knows he has unleashed the Terror of reprisals too, and he doesn’t want to realize that too much (he avoids any source of information), but he probably tells himself that all revolutions have a bloody path, it can’t be helped. And he does run the risk of saving little Dharam, the boy his family had sent to him in Delhi to learn the ways of getting money, like Uncle Balram.

We are now in Bangalore. Having escaped the police, Balram uses the money he’s stolen to start a rental company. What sort of man has he become? How does he live with his crime? What sort of retribution will be his? One day, something happens. An accident. One of his drivers runs over a boy on a bicycle. What will he do? He’s now in the master position. This time he clears his driver, and shoulders the responsibility. We are still in India, mind you, and corruption being what it is, he doesn’t risk much. He has bought the town police, and is acting in certain respects exactly like his former masters. But a half-baked moral perspective is now present. He goes to see the dead boy’s family, and pays them a hefty sum as compensation. He therefore recognizes the humanity of the dead cyclist, and the ties which linked him to his family. Even if Balram is still the former villager he used to be, and his consideration might be put down to underdog solidarity, or even payback, this is something that the preying headless masters would never have done, on principle, for fear of beginning to lose their status of “protectors” of the poor and the weak.

The exciting perspective that we have at the end ofThe white tiger is therefore one where good comes out of a necessary evil, and where this evil can and perhaps must be seen as necessary. Freedom from an existing evil sometimes (often?) needs to take the path of evil, so that freedom can win. Sacrifice isn’t always the best way, says Adiga. Sometimes (often?) sacrifice is just slavery. The coherent response to violence is sometimes another violence, because the greater institutionalised violence cannot be changed by non-violent means any more. Now of course this will shock and pain many ahimsa proponents. Yet, now that the codes of non-violence have entered the brains of violent dealers, now that Gandhi belongs to the institution, it is possible in India to pretend to be a Gandhian and benefit from the institutionalised violence (see Parshuramer Kuthar).

The trouble with Adiga’s initiative is that it advocates an individual, anarchic response in a society where the normal way towards reform is democracy. But he makes the clear point that India isn’t a working democracy. Nevertheless, it is hard to legitimate violent crime, and against a defenceless person, who is certainly guilty of certain crimes, but who hasn’t been tried legally. The book does it, and we must forget some of our western principles if we want to do justice to its purpose. Or rather, maybe Balram’s story forces us to alter our standard understanding of justice? On the other hand, it would be tempting, perhaps, to condemn him for abusive individualism: he decides to take the money and run, knowing full well what will happen to all his family. He chooses a freedom which means also comfort and affluence; and he sacrifices his family, whereas he already knew a better fate than them. One could only endorse this if one has cut away from a certain humanity, no? Well, perhaps like all revolutionaries, that is Adiga’s message, you sometimes have to cut yourself off from a certain type of humanity in order to reach out to a better one.

Only problem, the rarity of white tigers.

“You young man, are an intelligent, honest, vivacious fellow in this crowd of thugs and idiots (said the inspector coming to Balram’s school for a surprise inspection. In any jungle, what is the rarest of animals, one that comes along only once in a generation?

I thought about it a little and said:

“The white tiger”

“That’s what you are, in this jungle.” (p. 30)

A very thoughtful parallel is made by Jabberwock between Adiga's novel and Mohsin Hamid's The Reluctant Fundamentalist: go check it out!

March 2021: Addition for those who might be reading this review: maybe you've seen the excellent movie which has been made from the novel (here); it's very faithful to the book, and well worth watching! Lead actor Adarsh Gourav does a great job as Balram.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

(1) “I won’t be saying anything new if I say that the history of the world is the history of a ten-thousand year war between the rich and the poor. (…) the poor win a few battles (the peeing in the potted plants, the kicking of pet dogs) but of course the rich have won the war for ten thousand years” (p. 217)

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)