Jana Aranya: an education to the moral world

Publié le 5 Mai 2015

Jana Aranya (1976 - The middleman) is about a young man called Somnath (Pradip Mukherjee), who discovers that in order to succeed in the world of business you have to accept to compromise your principles, and find yourself losing an innocence which you didn’t know you had before you have lost it. We follow Somnath right from the credits, in a classroom where young men are cheating during an exam session at University; someone who seems to be a teacher is sitting powerlessly at a desk in front of the gleefully pleased students, who seem to relish as much the pleasure of cheating as the fact that they’re (half)watched doing it. An invigilator walks to and fro in the aisles, but he too is blatantly oblivious to what’s going on. The hero doesn’t actively participate in the collective cheat, but he doesn’t denounce it or resist it either (we see him asked to pass a piece of paper, and accepting to pass it on): his half-honesty is therefore seen to place him apart from the frauds, yet it also places him below what straightforward integrity would normally suggest: to refuse any half-dealing or even denounce wrong practices. The trouble is that, like the teacher at the desk, he accepts the wrong-doing which is happening in front of his very eyes, and doesn’t intervene to stop it. Such a toleration of bad habits is called compromise.

So the film starts as an analysis of this field of morals where you aren’t in a starkly good and bad context, that is, one excluding the other easily because the agents representing one side and the other are mechanically placed at each extreme, and the cost of these places is overlooked. We are plunged in the field of compromised morals where honesty and dishonesty are still present and still exert a strong influence, but where the evils are calculated as lesser or greater evils. This calculation is made depending on whether the person can cope with what it costs to relinquish innocence (and self-respect) to the point he or she won’t stand it anymore. The interest of the film isn’t in itself the exploration of this shady zone – it is commonly pictured in movies and books – but in the experimental dimension of the exploration, as it follows the impacts on the moral conscience of the hero.

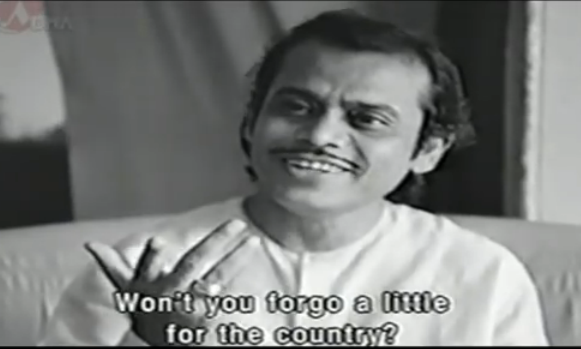

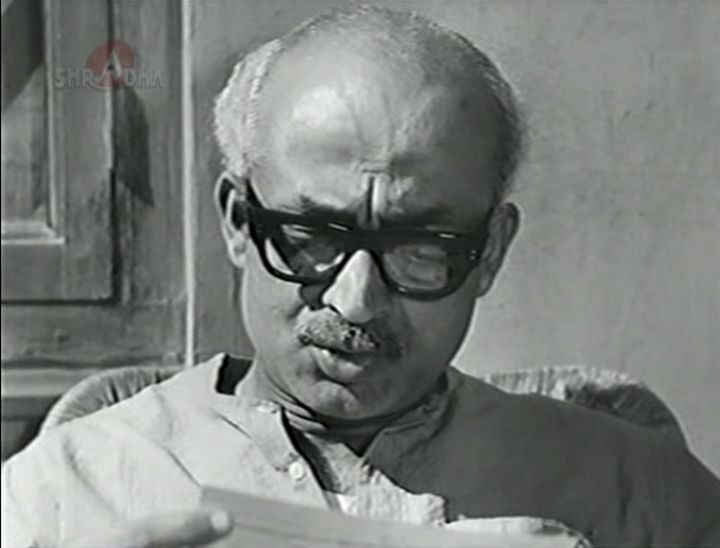

Here, I can’t refrain from paying homage to Beth’s review of the film, because she focuses sharply on Somnath’s character, and she does it very well. She underlines that he’s at an age, between adolescence and manhood, when maturity is still a goal, and one doesn’t know that it can be directed on the wrong track by imprudent decisions (I think Ray would have agreed that something like a misdirected maturity is a possibility). Somnath is guided by a strong superego, that of his Brahmin father (Satya Bannerjee) who confronts him with the necessity of honesty and morality, and even if this is shown as naive and traditional, enables him to feel when something wrong is beginning or at least has begun. But unfortunately, other less clear agents are present around him too. In one of the early scenes of Jana Aranya, a petty Neta – we aren’t told where he’s emerged from – tells Somnath and his friend Sukumar (more about him in a while) that if they want to succeed in life, they have to forgo something for their country. In his politically-correct way, it probably means: waiting a while in some menial job before hoping to move on, or perhaps allowing politicians to straighten up the country and not demanding everything here and now. Sacrifice – that’s what the complacent politician requires him to go through, applying for a job when he knows there’s 100 000 other candidates, letting go of his dreams of marrying his loved-one, trudging through the exhausting and absurd interviews. The politician claims he understands the “angry young men” of the present generation, but he can do nothing to help: “We haven’t been in power long enough”.

It is in this context of shifting influences that Somnath receives the results of his examination. Disappointingly, it’s only a pass. His father wants to file a complaint, or see somebody about it at University. ?)… Somnath hasn’t had the grades he expected at his university exams, so he can’t get the easy job they would have guaranteed him. Neither will his girl-friend have permission to marry him. What happened is that the teacher who was supposed to correct his paper had bad glasses! He gave him an average grade as a result of not being able to see the handwriting. Is this absurd bad luck? Or is there some hidden justice behind it? Ray doesn’t tell us. Perhaps in his exploration of the impact of moral choices he wants to tilt the scales slightly, and add a dose of misfortune? Is he suggesting that morality is easier to come by when you are given all the advantages? Anyway, Somnath won’t be spared the difficulties of moving out and fend for his own. The University result stands.

In his home, on top of the retired old-fashioned father, lives Somnath’s brother Bhombol (Dipankar Dey), and his wife Kamala (Lily Chakravarty), who tries to smooth the ups and downs of her brother in law’s life. She’s present when Somnath learns of his sweetheart’s announcement of marriage to somebody else than him, and she tries to offer him support. “Let me do my own worrying”, he retorts. And then comes a moment of insight into Ray’s cinematographic talent. Kamala suggests that perhaps Somnath’s sweetheart was forced to marry this other person: this would make their separation less painful. Somnath pauses, looks at his sister in law, and says she too had cried at her wedding: could it be that she hadn’t chosen his brother out of love, and that she had to relinquish somebody else? Kamala frowns and says all girls cry on their wedding-day. Why this little exchange? It does tie in with the movie’s main theme of compromising one’s desires and hopes to the complex realities of life, but this type of compromise isn’t morally wrong. It serves as an element of judgment as to what moral compromise really means. I think we should also see the episode as Ray exploring the depth of human relationships, their singular and multi-tiered reality. When people meet and interact, a quick observation hides the many levels of implications where the persons are present to the interaction, but such little scenes lift the veil a bit more and make us wonder about the adventure that human life is, with its mysteries and secrets.

The film gets on its main track with an important meeting. Somnath has just left yet another hopeless job-seeking interview (with questions like “what is the weight of moon?”) when he slips on a banana peel thrown on the pavement by a portly, bespectacled gentleman. It turns out he’s someone he knows, Bishu (Utpal Dutt), and he doesn’t know yet this banana-skin man is a “middleman”, a businessman whose job it is to find goods at a low price and resell them with a profit (again see what Beth has noticed about this scene). He doesn’t know yet that he’s already fallen in more than one sense:

This Bishu is a wonderful invention of characterization. Moustache, glasses, round eyes, he’s like a genial clown; you want to see which prank he’s going to do next. He looks like what Somnath might look like twenty years hence. No wonder they click immediately. But he’s the respectable entrance to the moral downward slope which we are going to witness. Somebody somewhere calls him Mephistopheles, and indeed he’s like the Devil, so sophisticated and well-mannered; although he deals in business and doesn’t hide its dangers, he seems to have retained a certain moral standard and will go out of his way to help a young aspiring middleman disinterestedly. Somnath, mesmerized, steps right into the trap:

BTW, the idea of a middleman is in itself quite telling: being in the middle is being where the compromise is easiest, where the indecision between good and bad is maximum. The middle is also the center, the most powerful place, but also it’s in between, and leaves little freedom, it’s like a prison. Later in the film, the Hindi/Bengali word is used, dalaal, meaning a broker, and by extension a pimp. The tragic thing is that Somnath will be trapped into becoming such a procurer, and Ray’s message is clear: dishonesty is like selling your soul away, as if it was an object to be consumed, and losing your soul, and with it, the name you were called, choosing another name than the one your parents gave you and becoming another, darker person. Having said this, mind you, I have to add that Satyajit Ray’s film isn’t a moral condemnation. Like all good moralists, Ray explores and explains the human situations in which moral choices are made, and introduces us to the complexity of intentions and decisions: nobody is irredeemably good or evil, and in his cinema there are no standard stereotypes.

So anyway with the help of his “launching-pad” (as Bishu calls himself), we now see the young hero move around a busy Calcutta buying goods, being driven nonchalantly with his stuff on the backseat, then selling it to crafty managers he’s trying to out-fox, and it works… He brags about his success to his friend Sukumar, when he comes to see him one day. Here Ray dons his socialist cap and shows us the difficulties of a lower-middle class family, their cramped premises, the father struggling with an underpaid job, the five children, some of which are sick, and Sukumar’s sister, Kauna, who’s supposedly working in show business (we hear Sukumar speak of rehearsals and money for makeup). She seems tired and spent, and he even has to ask Kauna to shut her window while changing – it attracts all the boys of the neighborhood:

An important scene, as you know if you’ve seen the film: Somnath witnesses the virtuous brother, but doesn’t comment. As yet he’s just surfing on the blank innocence which his education has guaranteed him and the attention which his flashy job secures him. For him, in spite of what he half-understands of the materialistic world he’s entering, it’s like a fun game. He’s got all the time in the world, he's getting some help from “friends” who make him earn the money which indicates he’s moving on in life: what more would you need? What’s interesting is how Ray makes us witness how Innocence works. Innocence is like an armor: it’s made of solid material which can resist many attacks from evil forces. But, at this stage, it’s blind: it doesn’t see the signs of hypocrisy, corruption and vice. One such sign is when Somnath is driven to town with one of his clients, and owing to the bumpy road (a clear metaphor) the glove compartment regularly falls open to reveal a racy book-cover. “I’m sorry if this bothers you” he’s told. “Not at all”, he answers candidly, and symbolically presses his fingers against the compartment to stop it from opening. Another sign is the name of the chemical he’s dealing with as per a contract with a textile mill: optical whitener! Doubly significant, because you can understand the name as applying to industrialists involved in shady transactions who need to artificially clean up their mess, but also because it might refer to Somnath’s murky eyesight (shown by his thick glasses) when entering into this dubious world: he would need some whitener to make things stand out as they really are! In this world of backdoor dealings and artificial respectability, everybody needs the stuff:

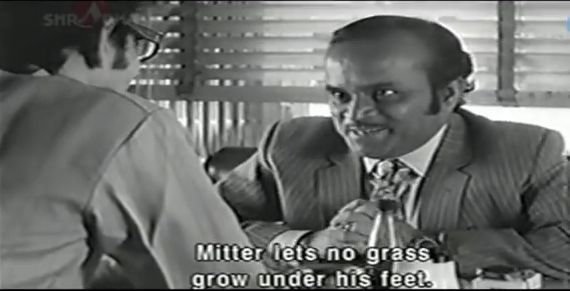

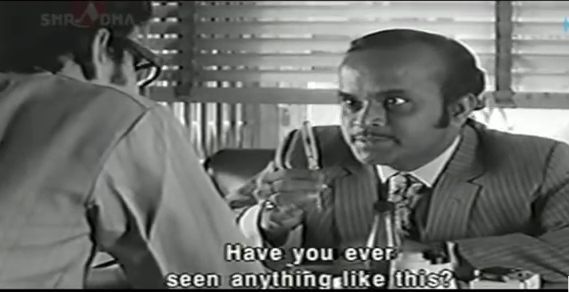

In the last section of the film, which introduces a new “middleman”, one goes down one circle (of the Inferno-like moral voyage): M. Mitter (a German-sounding name reminiscent of “Mittel”, meaning middle), aka “the PRO” (he’s played by an excellent Robi Ghosh, seen before in Abhijan). He’s introduced by yet another middleman, a M. Adak, who works in Bishu’s offices and showers Somnath with “advice”, to which the latter can still respond in his laughing, half-understanding way, as if it all was really entertainment:

If Bishu was the Devil’s civilized face, Mitter is his practical one’s. Do you know Attila, the legendary cruel leader of the Barbaric Huns? According to the saying, where he passed, grass never grew again:

And, like all good money-seekers,

Which, in our moral reading of the movie, means: a soul. Mitter has seen with his hawk’s eye that he has a prey to catch, a weak-willed, blind-innocent fly who’s let itself be caught in the net. Somnath is all the more a prey as he thinks himself superior: he believes he can cross through the world of business and come out unscathed, that its only a game where you just need to show you’re pliable and show honest intentions. Somnath’s permanent smile reveals his weak spot: he’s an innocent fool who doesn’t know that the world of money is a cruel, selfish and uncompromising. Like his glasses, which represent his blindness, his smile betrays him all the time. It says to people dealing with him: I’m a straight-dealer, trust me. But nobody trusts anyone in this worn broker’s world. Everyone counts before trusting. Figures come before faces. Somnath is soft; he should be blunt (not to say razor-sharp – but how can he? Sharpness comes from Experience, this wordly-wise satisfaction of having trampled other fellow human beings to stand higher than them, and become insensitive to suffering and pity):

Adak told him to look for people’s weak spots: he didn’t tell him Mitter was going to exploit his! It’s Ray’s cleverness to underline that Somnath’s is closely watched, for just after the meeting with Mitter and the advice from Adak about Mitter’s unfailing memory, we see him in a shop dealing for a batch of boxes where little eyes are looking sideways at him:

The razor moment comes soon enough. Not getting the assurance he needs about that chemical contract, Somnath calls Mitter, and he asks him to meet him at the barber. He’s now going to shave off any scruples the young man might still harbour:

From then on it’s all downhill. The sad moment when Somnath pulls the curtain between his father and himself, the frightening dinner where Mitter’s focus on his prey is so palpable it sends shivers down your spine:

There’s a glimmer of hope as Somnath, when presented with the arrangement organized by Mitter for him – bring a prostitute to the hotel where his chemical deal client is spending his evenings away from his wife – realizes the depth he’s swimming in, and hesitates: “Nobody in my family has ever…” Mitter finishes his sentence: “done anything wrong?” And then like a matador around a wounded bull, he plants dart after dart in his back until Somnath, his glasses off and uncovered (he’s rubbing his eyes as if in a nightmare he can’t shake off), is defeated. The last scenes of the movie are a masterful exploration of his Hell, where he walks like a dead man in the night, condemned to do what he should have seen he was preparing all along. Having flitted too close to the flame, his innocent wings have got burnt:

I’ll stop here this already too long review (and avoid giving away the end, if you don't know it), but there would be many other things to say, and not the least would be to study in more detail what Ray says of women through the film. His fight against misplaced virility shows quite strongly (but nevertheless in his usual carefully non-judgmental way) in Jana Aranya; certainly the latter part of the film would deserve a longer comment, with its careful examination of Mitter as a family man, the meeting with the woman whose drunken husband, this time, won’t let her go, then the depressingly trivial moment in the primly organized home of a mother who also organizes the meetings of her two daughters for the benefit of visiting gentlemen, the night car rides in between each of these failures, with Somnath flinching at each of them whereas Mitter whips on and finally finds the good horse… but he lets Somnath ride it. Sorry for not being more specific, the end is really good and I don’t want to spoil it. The movie can be watched here.

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)