Manzil (1979): do you mind lying and deceit?

Publié le 23 Septembre 2018

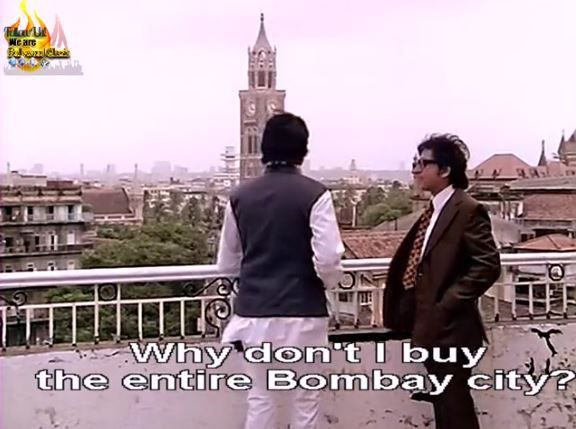

Have you ever wondered why you were born poor and not rich ? (if it’s the other way round, you often don’t wonder) Have you asked yourself why this injustice continues in today’s developed world? And if you are a victim of this injustice, have you never felt that, up to a certain extent, you should be entitled to take (or be given) what you need instead of working hard to earn it when others just enjoy it without doing nothing ? And finally, up to a certain extent also, don’t you condone the underdog who lies and frauds because society’s so made that it’s the solution he’s found in order to reach the satisfaction he believes he’s entitled to? These question are perhaps - or perhaps not - the ones we could ask ourselves after having seen Basu Chatterjee’s 1979 Manzil. I think the movie’s trying to make us pity Ajay (Amitabh) who’s in more or less in this position, and we, because it’s a feelgood movie tend to go along with the answers it gives to the problem. We let him lie and shirk work because he belongs to the numerous poor.

(Doesn't he look like Patrick MacNee from The Avengers?!)

This Ajay, the only son (it seems) of a lower-middle-class woman who’s been saving all her life, has reached a certain educational level (BA) but doesn’t look ready to give the professional world a real go, and because there’s a packet to be made, is content with accepting the offer of a suspiciously optimistic middleman, a mechanic, of investing into the business of electronic meters. He’s being swindled, but doesn’t realize it and opens a tiny office where he grandly answers the phone and directs the business. Meanwhile, he begins a love-affair with Aruna, the daughter (Moushumi Chatterjee) of a rich Bombay lawyer, who’s noticed him singing at a wedding. She’s also single, it appears, which I believe says something about the film’s simplifications. He happens to be singing RD Burman’s Rim Jhim gire sawan, so of course she is mesmerized. Who wouldn’t? Even I have been in love with this song for years before actually watching the film.

But I must say that I was pleased to see it, because this first rendition introduces us to Aruna’s ravishing friend:

Alas, she’s only there to enhance the enchanting song, and then disappears from the story… Could this mean the film-maker is using pretty faces to seduce his spectator and put them in a good mood, thanks to which he’ll make them swallow the film’s shifty morality? Anyway, what happens next is morally very worrying: Ajay feels he needs to lie about who he is, and pretend he’s somebody else, otherwise (we suppose he thinks) she wouldn’t reciprocate. Why on Earth, if the movie was the little jewel some people suggest it is (here), doesn’t Ajay say the truth about himself? Why does he immediately start a fraud about himself, when he falls in love? Was Indian society so skewed in those days that an aspiring young man of limited means needed to falsify himself to hope to court a rich girl? Were girls fools who could be thus manipulated? How come a film-maker could put up this sham? Was it because he knew a sufficient amount of his spectators would buy it?

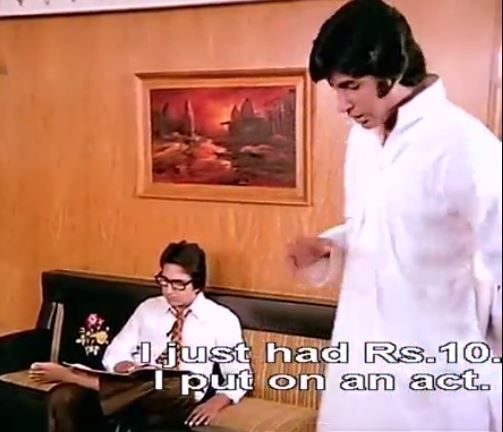

Because imagine: Ajay then uses his college buddy, Prakash (Rakesh Pandey) as nothing more than a means to an end. Almost without explaining anything, he tells Prakash he needs cash, then his flat, his car, his suit, in order to put up his deception of Aruna…And Prakash limply agrees! How realistic is that? At one later stage, when he’s caught red-handed, Ajay admits to Prakash, who knows it full well, that he’s faked it all, and so even if it’s in the name of love - love, which should mean truthfulness and sincerity -, he can get away with it and continue to count on his friend, and not even harm his friendship either… I suppose the spectator feels he can accept all this because Ajay’s been deceived too (he’s been duped in the business deal he’s contracted with Anokhelal the mechanic). But he doesn’t stop at his friend; he isn’t ashamed of wringing money away from his mother, and tells her a long pathetic tale about a golden future which will be hers when he succeeds in business…

But…It’s true that we have the 2nd rendition of Rim Jhim, that magical scene of a rain-drenched Nariman point, where Amitabh pulls a makeup-free Moushumi (it would be hard for her to have kept it! – but she looks lovely) through the puddles and deserted rain-swept streets, and her natural charm operates like never. But can this scene pull the film across the line of shabby double-dealing? That’s where we have to examine the initial questions: does Ajay’s attitude make sense because he’s been dealt a socially bad deck of cards? He knows the social divides are uncompromising, and if he wants to have any chance with the gorgeous Aruna, he has to show a profile she can allow herself to dream about. He just has to play the role, and we’ll admire him for daring. And when he gets caught by her righteously furious father, we’ll continue to be awed by his silence, his restraint, his poise… It’s once again the old DDLJ syndrome. Then comes that funniest of cinematographic inventions: Ajay’s seen learning the physics of meters, the same meters which had been botched to cost nothing to buy by the mechanic who used them to trick him into a fake bargain. He’s all of a sudden in a sort of lab where he’s fitting what we understand is a part of one of these electronic mechanisms on a vice, and correcting them, so to speak. And the message is (I suppose): guilt has shamed him into using his hands, those “good” instruments of success, as opposed to … words? Words which can lie and hide? Or otherwise what?

And so, because he’s begun using his hands, instead of his tongue, we glide along the path towards self-justification, which will culminate in the trial. All will end well, but I will continue to feel that in spite of the morally right tilt of Ajay’s morally wrong actions, Basu Chatterjee’s double-dealing isn’t quite right. Is it because he’s made to perform it with perfect ease, perfect cynicism? Perhaps… It’s also because we spectators are supposed to buy all this without demurring – yes it’s unjust that the poorer must work harder and that the richer have it all laid out. Yet, there’s a dignity in accepting your fate which is greater than lying in order to fake another one. Such a dignity should be vindicated and left where it is. Ajay made to capture it when he reverts to manual work is like stealing it. (I didn’t know I was such a Marxist!)

I realize that I’m rather severe about Manzil. Some readers will prefer, perhaps, Anu’s take. I must say I can't really agree with her, much as I would like it. Sharmi thinks somewhat like me, but I repeat my grudge: it isn't because Ajay's such a liar and a shameful deceiver that I have trouble with him. As Anu says rightly: "And you haven't met charming ne'er-do-wells who want to get ahead by hook or crook? No one says he is a nice guy; all I'm saying is that it is not completely black and white.” What I begrudge the film with is Chatterjee’s simplified use of flashy shortcuts as if everything was okay with that. I think there should be more consideration for the simple guys who are stuck in dire straits where no easy and cheesy escape for them is possible. BTW, Mrinal Sen’s Akash Kusum is the source for Manzil. But unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to exist with subtitles. So, until some kind soul lets me know when it is…I rather think it would be a little more sophisticated.

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)