Silsila, the spiciness of exposure

Publié le 25 Juin 2018

So much has already been said about this Yash Chopra 1981 movie… And here I am adding to the pileup! Well, I hope it won’t be too long and too boring to read. In fact what I want to say can be quickly summed up: I’m perplexed at actors accepting to stage publicly an embarrassing intimate relationship, and wondering what’s “behind” it. The rumors concerning the Amitabh-Rekha affair seem too insistent to be false, and Jaya Bachchan must have known about it of course, so how could the trio manage to play the roles they played in the film without feeling even more embarrassed? There. I’ve voiced one of my concerns, but there are other levels to the questioning. For example: how much do (or did) actors - in India at that - accept to use their intimate feelings and potential moral wrongdoings in order to ensure revenue or reputation or both? What amount of trapping by directors or producers would their contract have included ? Or: would there have been a possible (implicit? explicit?) way for a director such as Yash Chopra to convince people like the Bachchans and Rekha to transform their life relationships into film material in order to transmute them somehow, or give realism to the film? Or even: is it possible all these people might have taken part in the film as an exercise without any “real” connection with life outside the studios? And finally : could it be that some of them wanted (needed?) to deny the rumors so much that they took the risk of playing the rumor-filled roles so as to give the public the impression that nothing had in fact happened? (and could some of the public have bought this?)

Here and there on the blogosphere I have read a lot of things like this: “The scenes between Chandini & Shobha when they confront one another are subtle yet incredibly powerful. It is at that moment that it hits you - that these 2 women aren't really acting anymore - they are just saying things to each other on the screen that they could not say off.” (here) – But does this happen?! Can one “speak” to another person on the screen as one would have done in real life and was stopped from doing so? Can the screen be a possible confession-booth where secrets can be voiced because real-life situations/conventions forbid it?? Until somebody like Jaya Bachchan herself comes to tell me yes, I’ll never believe it. The screen is a 90% calculated effect zone where almost everything that takes place there is geared towards the effect on spectators (there can be some unforeseen elements which escape the editing team’s attention, of course). I think Yash Chopra has realized that with this “secret” he had a dimension for his film which must be rather rare to possess to such an extent: Silsila becomes a paheli, a puzzle in which one can try and find gossip-like trivia about a situation which everybody can guess and imagine to the best of his knowledge and that even now, almost 40 years later, continues to tickle the brain.

So that for me, much of the film’s interest lies in these unanswered questions and how the movie plays with our expectations. There’s a tantalizing “HOW?” in each of the scenes, and I must say, especially in the scenes where Jaya Bachchan is present because she’s the one who ran the greatest social and moral risk in the business. I could never cease to wonder how she managed to pull it off. Of course, there is the story’s own answer: like Shobha, her character, she knows she is the one which the whole of the Indian traditions backs; and that, provided she keeps her cool, all these conventions are in favour of mending her wronged wife status. Could this have weighed enough for her to accept to play the role of the betrayed spouse? On the surface, especially thanks to the (rushed-up) ending, she’s made to embody the victorious force of the socially acceptable Indian marriage norms. But so many other forces in the film are working in the opposite direction! Agreed, the fact that the film was a flop when it came out seems to say that these opposite forces weren’t strong enough then, and that Chopra’s gamble (modify the public’s feeling about infidelity to the extent that it became “humanized”) was a failure. But who knows if the old fox wasn’t gambling on a plane which reached further than 1981, all the way to the future of India’s stilted social norms (they would enter the history of cinema as brave forerunners)? Because I’ve read that the movie’s reruns refunded it rather well.

So in fact the film could well be doing two things at the same time : reminding (reassuring) its audience of the morally and socially acceptable marriage ideals, and at the same time examining the complexities of feelings and their implications in the face of the said ideals. And in doing so, it gives credit to these feelings, it gives them sufficient exposure for everyone to understand and possibly accept the necessity of certain situations of infidelity. It could be said that Chopra doesn’t choose between these two options, but given the situation in 1981 India, his lack of choice is in fact a clear choice for the exceptions to the rule: his stance must be that there are cases when infidelity does have a justification. And so perhaps, if this was the director’s stance, he might have interested the actors in nailing this in for the Indian audiences of the day? They might have felt it their duty to uphold this daring position: given the circumstances, some infidelity is acceptable.

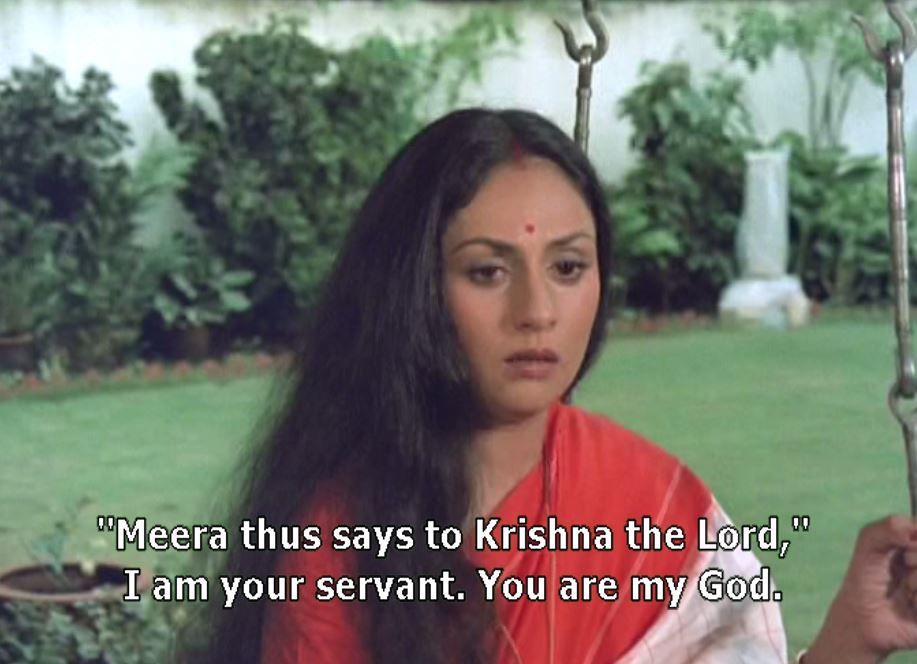

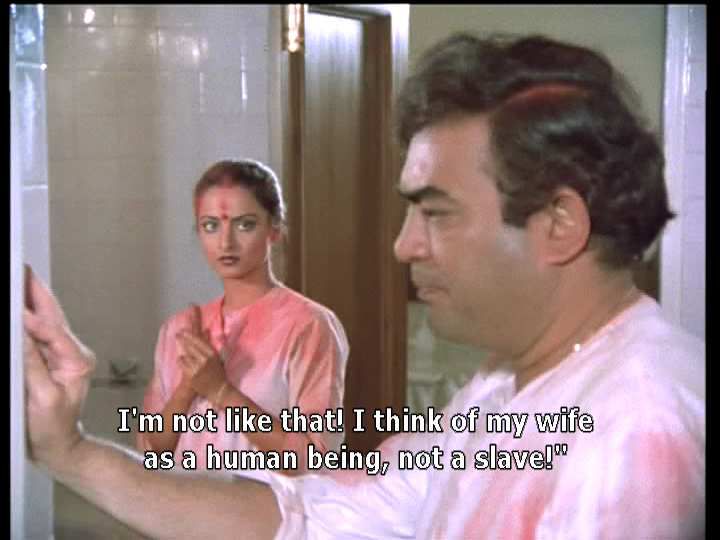

And clearly, the circumstances in Silsila are more than acceptable: they’re purposefully designed to make infidelity seem logical. This logic takes the form of “human” as opposed to godlike, in the sense that marriage can and perhaps should remain at the level of a human affair, an affair between human beings, not godlike ones:

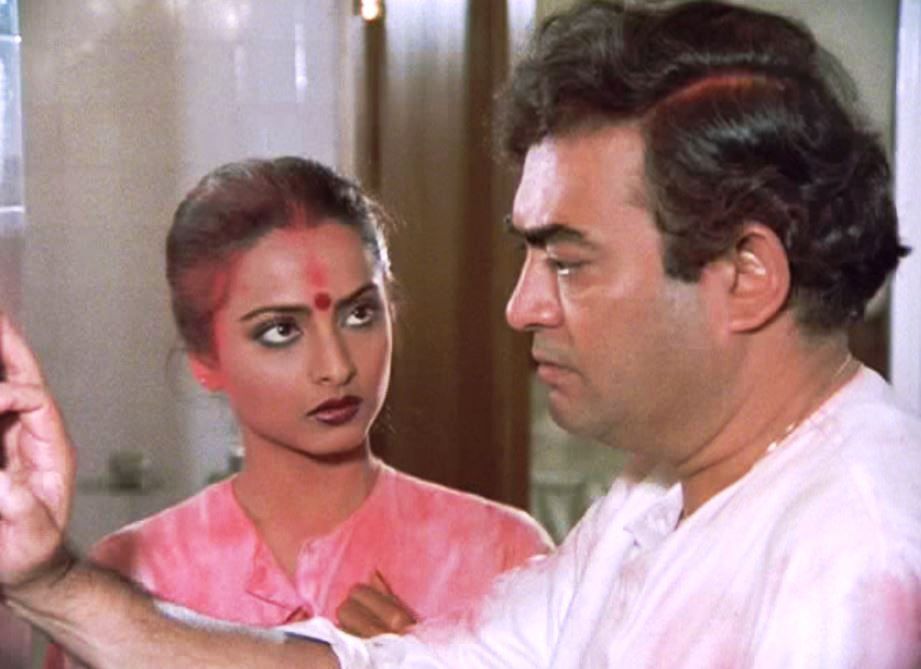

This requisite is nothing more, in India (and perhaps more in 1981 than today, because things must have changed a little), than tilting the balance upside down: if marriage is only a human business, if a husband is no longer his wife’s godhead, well then it’s quite acceptable that one should part if one can’t stand one another anymore. Unlike gods, human beings make mistakes. This position in fact is upheld in the film where one would not have expected it to be upheld: in the conception voiced by the betrayed Dr Anand himself. You will remember that he’s the deceived husband (played by a fine Sanjeev Kumar) who quickly notices something fishy in his wife’s (Rekha) attitude, and whereas one might expect him to insist on the husband’s prerogatives that his wife stop playing with another man (Amitabh, who plays Amit the aspiring writer – he’s actually given his real name), instead he pleads for a relationship in which his wife is treated as a human being, not as her husband’s slave:

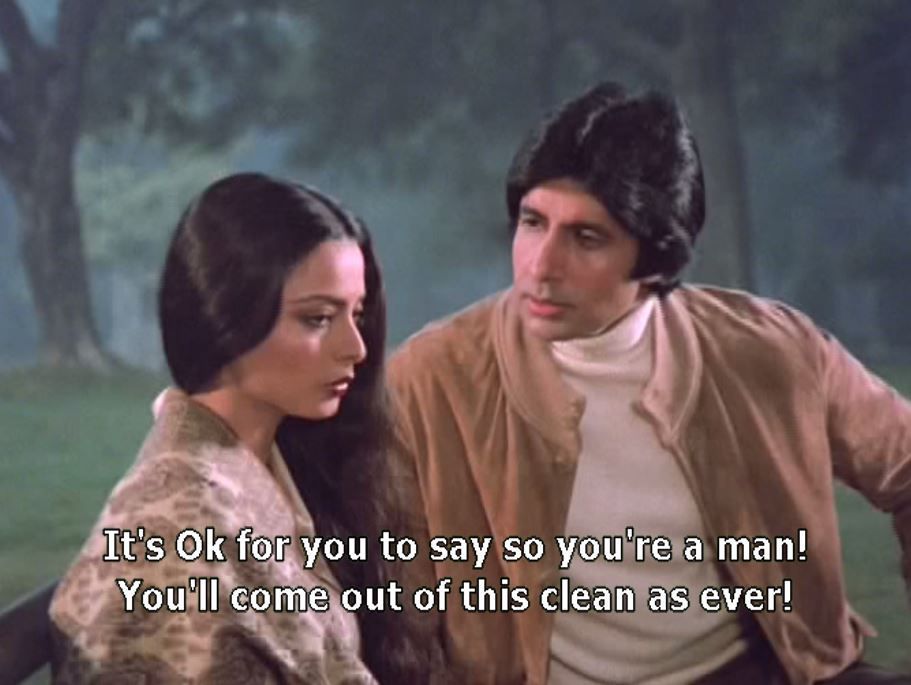

And the implication of this is that she’s entitled to her feelings, her aspirations, her decision-taking, etc. This runs against much of the traditional strictures which the movie is questioning:

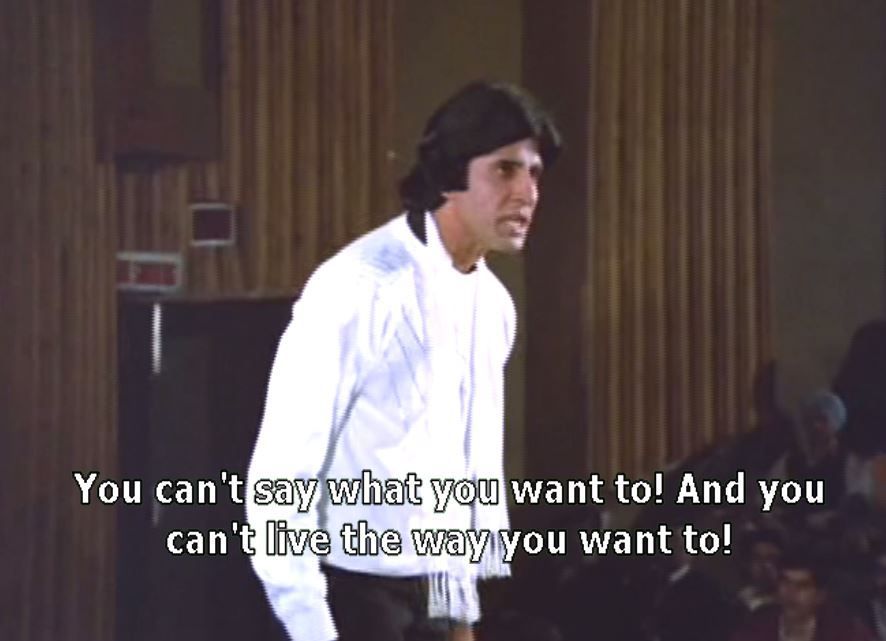

And this also corresponds to Amit’s plea for liberation, staged by himself at the beginning of the film:

Now I think a special treatment has to be given to that famous Rang barse song scene. Many viewers consider it one of the movie’s best. Probably because of its provocative nature, because Amit is seen courting Chandni in a very free and clear fashion, and the other two, Dr Anand and Shobha are seen staring and understanding at what’s happening but unwilling or incapable of stopping it because there’s the pretext of the holi dance and Amit’s (transparent) sharabi.

For me, everything is calculated in this scene to provoke the kind of ambiguity which has been alluded to already: on the one hand, the outrage at being obliged to undergo a scandalous public display of infidelity, and on the other the realization that love and desire is stronger than the any social norms and if it plays like this in the open, fearlessly, then DDLJ! There’s no dulhaniya here, but the feeling is as strong, I believe. Love carries its own justification, up to an extent: it transgresses barriers and frontiers, it can be wrong morally, but somehow it’s always right if it’s genuine. Many films and stories work on this principle. The subtlety here is that we can interpret the scene both ways, and I’m pretty sure M. Chopra wanted it that way.

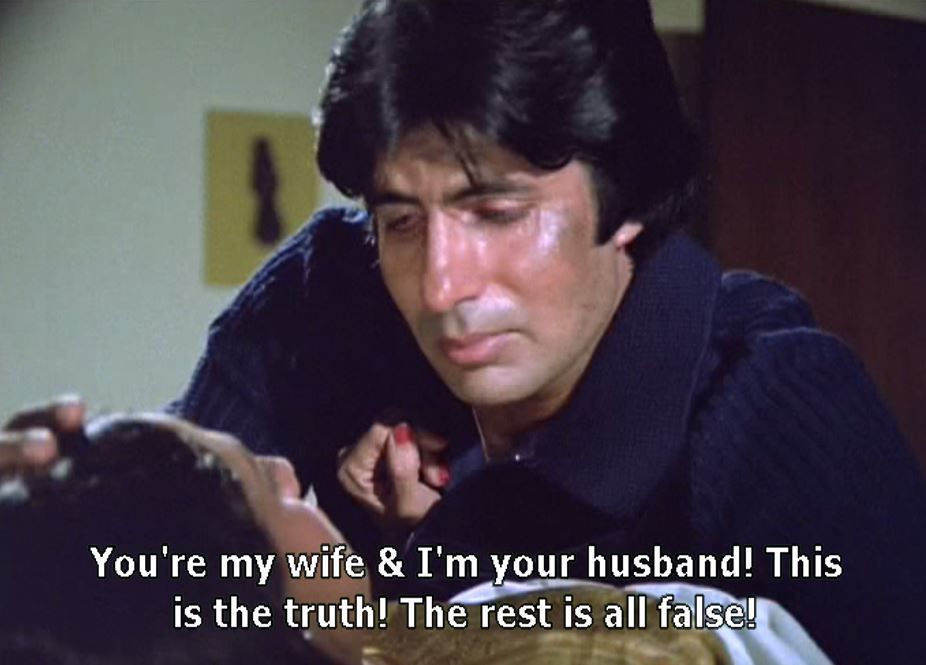

There have been other Indian films about unfaithfulness, notably Kabhi alvida na kehna, which struck me as more contrived (but it’s a long time since I watched it): so what value should one give to Silsila? Does it have intrinsic qualities which justify its reputation apart from the fact that it’s a landmark movie based on some well-known people’s love-affairs? I’d say yes, in spite of all the flaws which it’s afflicted with. First there’s Amitabh’s acting, helped by Sanjeev Kumar and Jaya Bachchan. All three strike me as believable and complex, notwithstanding the added depth coming from their private-public dimension (this doesn’t concern Sanjeev). I admire how Amitabh manages his big frame and even uses it to express his strength and presence. He captures Amit’s duality rather well, a man who strives at being at once a friend and a lover, and he expresses the difficulties of the situation rather poignantly:

Jaya Bachchan deserves a special mention, because as I said before her role is the hardest. I was sensitive to how she purses herself, how she suppresses her suffering, and how she sometimes gives way to it, making it all the more palpable; her whole persona is a well-balanced mixture of resignation and spirit. She has a mother India inside her, and at the same time she’s frail and exposed. She holds her ground in front of her rival, even though she knows that certain emotional odds are against her – but she’s certainly made a statement about herself:

There is something (a strength? a vulnerability?) which she manages to suggest in her acting and at the same time to hide, almost as if she was still a child or a young girl; it’s a subtle dignity, a certain presence which comes from her innocence, I think. And she has this slightly askance head position which reveals how this something inside her is right in spite of the circumstances outside which wrong her :

Rekha as Chandni is unfortunately the weak point of the characterization (and of the real-life trio?) Trouble is, both Amit, her tall dark partner, and her sprightly and astute husband Dr Anand (Sanjeev) overshadow her at every turn. Her looks are “lovely, dark and deep”, as Kali-like as possible, but they can’t make up for a rather uncertain acting; she’s opted for a low-key, submissive attitude which works partly, but somehow doesn’t erupt when it could have: if she had really loved her man, then why can’t she fight and tear out for him as the tigress she ought to have been? There was room for that. There’s something lacking in her just as they’re something present in Jaya/Shobha. So, question once again: did the actress not believe she had the right to assert herself, knowing that the woman didn’t have this right in real life?...

Whatever the truth or lies contained in this story’s background, it still provides the pleasant thrill of watching Bollywood’s greatest stars screening their lives in a tantalizing cinematic formula (or maybe, having it screened, who knows – so I hope their investment paid well!)…

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)