Kaala Patthar, Yash Chopra's Heart of Darkness

Publié le 11 Mars 2008

Kaala Patthar (“Black stone”) is a grandiose epic movie by Yash Chopra which is at the same time a political and social weapon against reckless capitalism and the exploitation of workers, a story of redemption and sacrifice, and a suspense-full entertainer, with action, love and fighting. There is in Kaala Patthar a power which comes from the outstanding performances of the great number of star-level actors. Amitabh is leading the list, but Shashi Kapoor, Parveen Babi, Shatrughan Sinha, Neetu Singh, Rakhee Gulzar, Prem Chopra, all have good roles to defend. But I’d say they would be less interesting if it wasn’t for another actor which transcends individual roles, and that’s the community of miners. Indeed, a lot of the power of the film comes from this ever-present “band of brothers”, this proletariat who lives together, grieves together, rejoices together, and dies together. As soon as an incident happens in the mine, and the siren sounds its distressful wail, everybody runs to the wells, in one single body. This unanimity is one of the most beautiful messages the film has to share.

Of course there are some exceptions to this general solidarity, and among them Mangal (Shatrughan Sinha, excellent performance) the escaped prisoner is at first sight the most obvious.

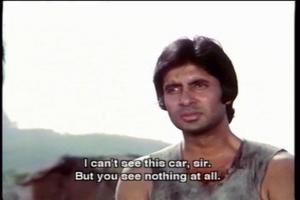

He arrives at the mine one day, looking for a good hiding-place, and his independent and fearless personality asserts itself quickly, creating enemies and friends as he strides past. Soon he has to measure up to Vijay (Amitabh Bachchan) who is like the soul of the mine, always devoting himself to the rescuing of endangered lives, and defending the workers’ rights, in spite of shocking working conditions. By the way, the mine-owner, a big bad capitalist, is a weak point in the film. I can’t see how any person in his position would be as short-sighted as not to combine his own interests to that of his workers. Perhaps I’m an idealist who doesn’t know much about Indian industrial history, but a minimal economic flair understands the necessity of some humanitarian concern. Of course, one could say the story needed such a villain!

In this very violent and dirty environment, there are women, and the three figures of the young doctor, the bangle peddler and the educated journalist bring both a breeze of freshness and a sense of completeness to the society of the mine workers. In their own way, these women are their indispensable companions, their defenders, and the proof that the community, in spite of all its suffering and degradation, remains human. The doctor (Rakhee Gulzar) has dedicated herself to that community because of her powerlessness, when she was a little girl, at watching her father die away from all medical help (we see her confess this painful memory as she stands behind the bars of her window, and in the same way, we will hear Vijay’s confession as he stands behind a trellis – two symbols of imprisoned hearts who have accepted to remain behind the bars to partake the lives of fellow-prisoners). Then Channo, the sprightful peddler (Neetu Singh) is a helper too. As Vijay says, she doesn’t just sell bangles and rings, she sells dreams, the dreams which are an indispensable element of equilibrium in that inhuman miners’ life, the dreams that prevents them from becoming crazy with grief and loss. That she falls in love with Mangal, and plays her part in redeeming him, is no little feat. Last but not least, Parveen Babi plays the dashing young journalist who will not trade her ideas and principles in spite of the threats and risks of being so near the jaws of the greedy and ruthless Moloch.

At the centre of Kaala Patthar, there is Vijay’s moral ordeal. First presented as an element of suspense, his mysterious presence at the mine is that of an improbable righter of wrongs who displays as much anger to defend virtue and fight against oppression, as Mangal the murderer will display in order to assert his own selfish and brutal rule. The confrontation between the two men is one of the film’s great assets (even if it is underlined and made cheap by an exaggerated musical accompaniment). One realises that “something” is happening in this confrontation which will have a connection with the director’s intentions. So when we learn Vijay’s story, his naval officer’s demotion for cowardice (he has abandoned his vessel during a storm at sea), we understand that he is at the mine to atone for his sin, and as he says: “I saved my life once, now I have to save my soul”. He has chosen to work in this human pit because he himself has fallen in an abyss of self-debasement. He is inflicting on himself the punishment which he believes corresponds to his crime. And so he counts his life and his suffering for nothing, and can only find peace by saving lives today that he hasn’t been able to save yesterday.

Those of you who have seen the film’s poster have no doubt been struck by that picture of a gorilla-like Amitabh, his coal-covered face distorted by a scream which is at the same time a yell of pain and a shout of revolt. This “scream”, vaguely reminiscent of Edvard Munch’s 1893 canvas, with which it shares an element of anguish and tormented pain, is (according to me) the visual expression of Man’s rebellion against oppression and exploitation. When Albert Camus wrote L’homme révolté (The Rebel) in 1951, he had in mind the justification of the revolutionary forces which can guarantee human dignity and social justice. Camus was an atheist and a humanist, and his call for man to rebel against forces of oppression was a call for meaning in a world fraught with the absurdity of violence and suicidal emptiness. Like Marx, he believes in man’s own resources, and he wishes to prick his fellowman into a form of action which will give meaning to life in spite of life’s absurdity. Let us say this is the film’s Marxist, or revolutionary dimension. But I’m going to develop the Christian interpretation.

The symbol of water in the film is a powerful one. From the beginning, we are made aware that there is a risk factor in the mine, because of the presence of a nearby lake which threatens to flood the galleries if digging is carried out too far. Shashi Kapoor is the young engineer who embodies the voice of reason and warns the mine owner of the existence of this risk. But of course the latter foolishly doesn’t give a hoot in Hell about such a risk. And as Vijay discloses his own story, his cowardly escape of his ship during a violent storm, the flooding of the mine comes to represent both his former crime and a chance for redemption. Water is an ambiguous symbol in art. It can mean either life, or death; purity, or treachery. Here it means both, and the strength of the film rests on this type of symbolism. Vijay’s is purified from his sin, and he fulfils his expiation because he saves the lives of his fellow-sufferers, having sacrificed his own. He doesn’t die, but his alter ego Mangal does. After having been saved himself (after an accident, one among the many which form the basis of the political denunciation of the workers’ conditions), and made peace with his enemy, he realises the value of sacrifice and offers his life as atonement for his former sins. So the water is Kaala Patthar can be both read as symbolical of the Deluge and baptism: it drowns the evil and cleanses the souls.

One final comment about the imagery of the mine. Writers Javed Akhtar and Salim Khan, together with director Yash Chopra have used the mine, its blackness, its depth and its danger to great effect. If there is a symbolism of water in the movie, there is also a symbolism of the mine. I am sure one doesn’t betray the film’s intentions when one sees it as a metaphor of fallen humanity, of humanity under the rule of violence and sinfulness. Deprived of divine grace, man has fallen into a bottomless pit of his own making, where there is no light, no guidance, but where murderous violence lurks to punish him of his folly. In that respect, the mine is our human condition, our common ground, and what can free us from its darkness and its violence is nothing less than sacrifice and disinterestedness. Vijay is no less a Christic figure than Mangal: both have tainted souls, of course, but let us remember the teaching of Paul in 2 Cor 5,21: “For he hath made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him”. Christ has been identified to sin so that he could save us from our sins. Christ is also believed to have visited Hell on Holy Saturday (as it is proclaimed in the Apostles' Creed), a “place” which has is traditionally associated with the Nether World. The resurrected Christ visiting Hell has always been understood as God’s desire to make himself known to all humanity waiting for its own rising from the dead.

So I’d say that the mine has an anthropological dimension: it represents the human heart. It is Yash Chopra’s Heart of Darkness (cf. Conrad's novel). When he entitles his film “Black stone”, this of course refers to coal, but also to this blackened and hardened object in every man’s breast, which Ezekiel had prophesied would one day be changed to a “heart of flesh” (Ez 11,19). The heart is as deep and dark and murderous when it is deprived of the light of love and self-sacrifice. It needs the waters of baptism and the works of charity and solidarity to be brought back to its former godliness. And no matter how deep and dark it is, it can always be filled with love and joy. These exist in greater quantity than violence and evil, such is the film’s hopeful message. One might think that I am reading too much Christian symbolism in this Indian film; I am the first one to be conscious of it. But I also believe that it is the privilege of great works of art to lend themselves to a variety of interpretations, and it seems to me that there is a great coherence in what the film has to offer in terms of this Christian reading. And that Kaala Patthar is also a plea for social justice only reinforces this opinion. Masterpieces coming from all over the world are understandable by other systems of thinking precisely because they are masterpieces.

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)