Dilli ka thug: a gallery of masks

Publié le 28 Mars 2009

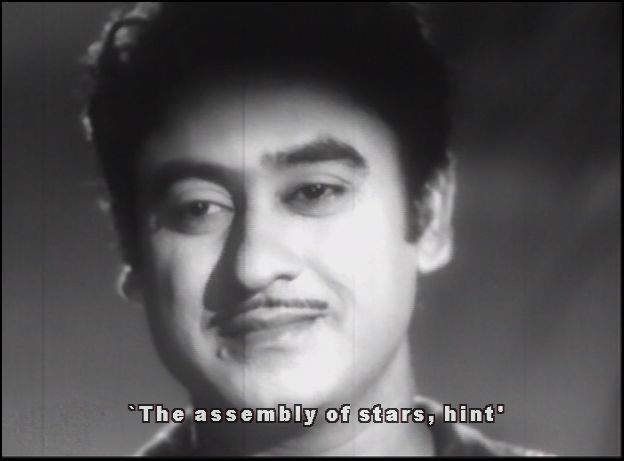

Dilli ka thug (1958) might be tossed aside as a jumble of loosely connected narrative titbits that have been put together for two main purposes: Kishore Kumar’s clowning, and Nutan’s youthful charm. A messy God seems to have been presiding over this movie, viz the DVD box received from Nehaflix, where the title reads “Dilli ka thag, starring Kishore Kumar and Mala Sinha”… It tells the story of a petty “Dilli” thief who falls in love with the girl he was supposed to be engaged with but whose family rejected him for some obscure reason, and this takes place in the context of a fabricated medicine scandal. Kishore the apprentice thug will become the hero who will expose the real thugs, those who kill ill people with their doctored drugs. Now, how on earth is this strand connected with Asha, his love interest? Let me try and remember… Oh yes, she’s the niece – or supposed to be – to Amarnath, a novelist who really is Anantram, the false drug tycoon, who killed Kishore’s father for not wanting to collaborate with him. Get it?

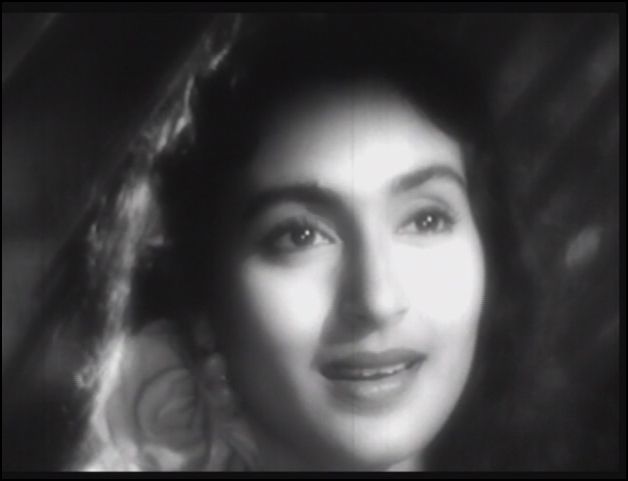

So coming closer to Asha, Kishore gets involved in the police chase for Anantram, and of course ends unmasking him, hurray! On the other hand, Asha is a swimmer in the film (no this isn’t a pretext to show her in bathing suit) who will rescue her drowning Kishore, that is, when she has decided he’s lovable enough. Well! Those of you that need a solid story to guide them along will have to just leave. Unless… unless precisely you’re also interested in the pleasure of just being entertained and follow a charmingly old fashioned manhunt filled with improbable twists and turns.

The film is a comedy, but also a carnival, a game of hide and seek. Everybody wears a mask: Kishore to cheat without being spotted, and to woo his maiden (she sometimes sees through him) ; Anantram to hide a horrid face-burn who would reveal his identity and his undercover dealings; even the innocent Asha at one stage assumes a borrowed voice to trick Anantram’s girl on the phone. Kishore also passes from one garb to another to fool a bunch of puppet-like corrupt industrialists who will oblige and notice nothing!!

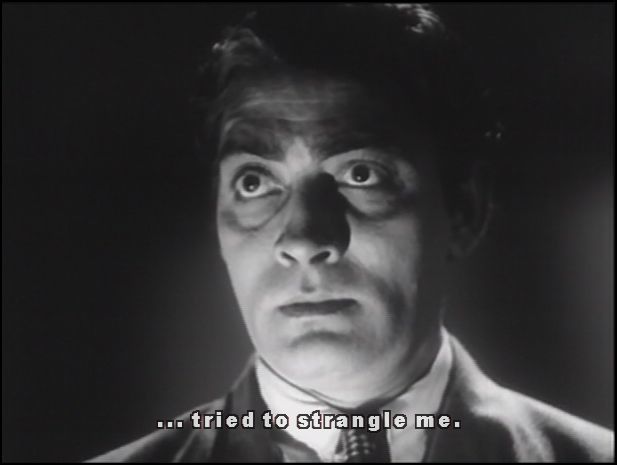

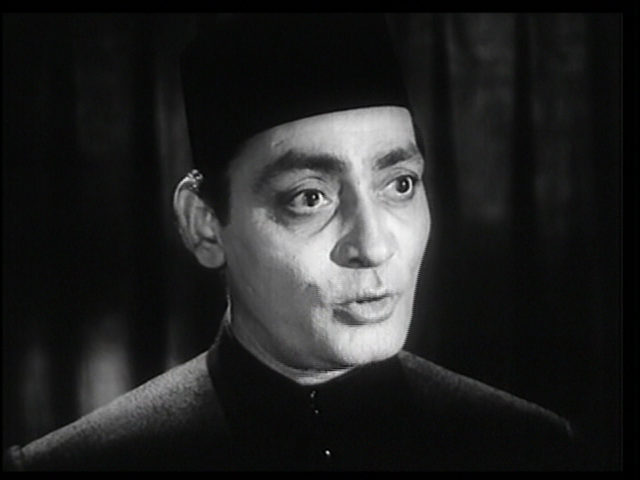

Our face is our main identity card: if we play with it too much, if we crumple it, we risk losing the social link that binds us to the rest of society. This is what happens to Amarnath: the accident in which he burns his face is the symbol of his departure from the code of morals which structures society. And hiding that face under several masks only underlines the criminal falsehood of his attitude. But the film-maker has been keen to draw our attention to this ambiguity of modifying our essential nature: his masks have an ominous and disturbing appearance, as if what is underneath was modifying the surface somehow. The novelist’s impeccability is almost monstrous.

If this is so with Amarnath, how come we don’t feel the same with Kishore’s masks? Basically because his face is always discernable through them. His truthfulness is always visible, even when he hides himself with a fake beard. In fact he doesn’t hide as much as he disguises himself: he’s a clown, wearing several carnival outfits, and playing his tricks. That’s what cinema is for, by the way: the masks we see on the screen are now good, now bad: our role is to discern which are which. I don’t know if you remember the change of face that occurs when Kishore sings that moving song “Ye raatein yeh mausam” with Nutan: I really felt at that moment that he abandoned all pretences, and that his face shows it. We see his solid, serious profoundly good-natured face, and he presents this fundamental goodness to his beloved one. A certain bashfulness otherwise forbids him from being too direct with her, and he is constantly fooling around with his face and general appearance in front of her, so much so that she doesn’t like him at first.

Asha (Nutan) represents Beauty: a beautiful face can be seen as another mask, whose power is opposite to that of the beast’s mask, or the clown’s. Many women (some men too) tend to hide that power by using devices which will protect them against exerting too much of that power, or too often. Sunglasses are the best known of such devices, but there are others, like a stern face, or averted eyes. A religious scarf fulfils the same function, by the way. It can be imposed from outside, or self-imposed, even if the face isn’t beautiful, but it does show that as such, faces are where seduction is concentrated. Naturally seduction means power: one might refuse to wield it, or on the contrary decide to increase it! All masks have that ambiguity. What is the holder doing with his mask? Does it represent the person behind? Is it truthful or not? When Kishore unmasks Anantram in the plane at the end, he clearly faces the thug’s truth, and obliges him to confront others truthfully, because they see him now as he really is. Similarly, when, during the song we mentioned, Kishore looks at Asha with his grown-up, mature face (as opposed to that clownish, playful one he constantly changes during all the film) he is showing her his truth, and she is letting him admire the beauty of her truth too.

In Dilli ka thug, there is an expressionist exploration of the effects of emotionality on people’s faces: this refers to the characters we have mentioned, but it also affects Kishore’s mother, when she is led to believe her son is a fraud and a murderer; Kishore’s face itself is transformed by the revelation of Anantram’s real nature. Love is I believe a powerful revealer of the inner self; it makes one’s truth come out and display itself on our “interface”.

You can find some additional comments by bloggers here: Memsaab and Maja.

And to finish, the haunting love song Ye raate yeh mausam:

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)