Sone ki chidiya, pure gold does not fear the smelter

Publié le 3 Juin 2018

Watching Sone ki chidiya (the golden bird, Shaheed Latif, 1958) has been a bit of an adventure, because even though I knew it was good, it doesn’t exist with subtitles, and some time has passed before I could get round to understanding everything. And here I need to thank Madhulika Liddle of Dusted off fame, whom I appealed to in search for explanations, and who very helpfully answered my questions and gave me lengthy explanations. I am also indebted to this book: Take 2 by Deepa Gahlot (published in 2015), who lists “50 films that deserve a new audience” in which Sone ki chidiya is filmed and evaluated. Maybe I’ll speak about it soon. Those of you who haven’t seen the film can watch it on Youtube here. And the story can be found here (thanks IMDb user!).

The film’s important for a fan of Nutan because it’s placed almost at the beginning of her career (even if it’s already her 16th movie!) and tackles some essential things in terms of cinematography. We owe this to the perceptiveness of its author, Ismat Chugtai, the feminist urdu writer and educator who wrote the screenplay. She became Shaheed Latif’s wife in 1943 and was repeatedly sued in court for her progressive views on womanhood, motherhood and sexuality. In the film she is questioning the role of actresses, the way they’re used, and the values of the cinema as an art and social instrument. Nutan being the lead role for this critical story meant that she endorsed some of its ideas and struggles, and her career can be better understood thanks to the movie (check the comments for a discussion of this statement).

Basically one can say that Sone ki chidiya tries to make sense of what cinema means in terms of social improvement, and naturally it’s very critical of the drifts which the exploitation of artists and the financial profits to be drawn from the silver screen meant for it as an art. And as actresses are one of the most important cinematographic commodities, it’s logical that Chugtai’s screenplay focusses on a young woman’s place in the business. The title of the film says it: new young girls are an immediate potential source of income (a golden bird - does the word in Hindi carry the same double-entendre?) and clearly this commodification was one of the main reasons why actresses had a bad rap in the past. How could they perform on the stage and still maintain that their bodies and faces are not for sale? On the other hand, such heavy questions are made lighter by the film’s humour, which also serves to alleviate its (melo)drama.

So it all revolves around Lakshmi, played by a fine Nutan. Lakshmi is an orphan who’s first dumped from place to place by relatives who don’t want the burden she represents. Soon enough though, the ironic opposite will take place, and everybody will want her! How? Well, she’s an artist, she likes poetry, singing, art and luck has it that one day she’s noticed by people involved in pictures. And here’s the first trait of humour: photographers come to the home where she’s kept by greedy “bhaion” because she provides them with her contract money. As soon as the photographers appear, everybody in this hare-brain family want their picture taken, and they crowd in front of the camera, actually hiding Lakshmi behind them and obliging the photographer to look for his model!

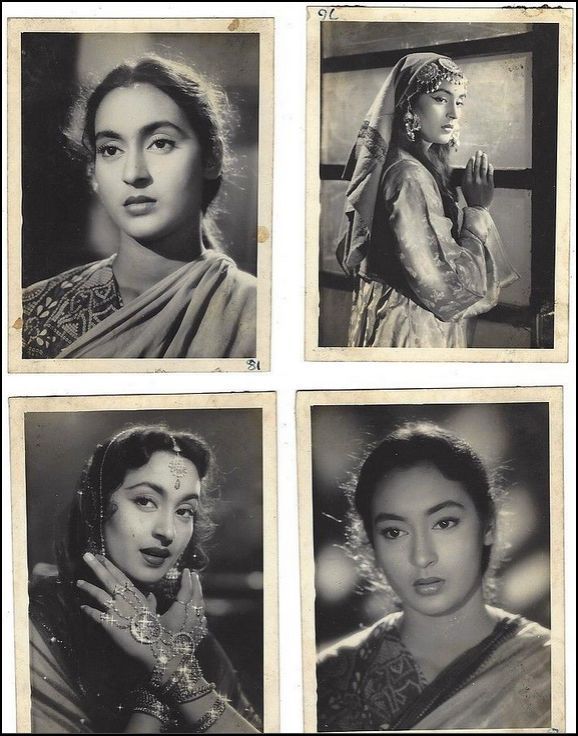

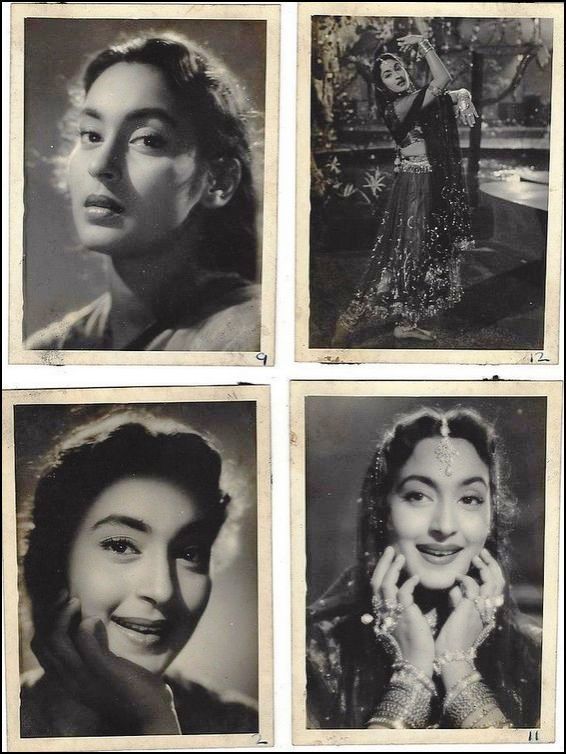

Can you spot Lakshmi on this picture?? Yes! Precisely, she’s in the frame on the wall! That is, the real person is obliterated and only her cinematographic two-dimensional picture is important! (and in case you haven’t seen her, Lakshmi is that little quarter of a head behind the ecstatic woman in glasses…) I don’t know if it’s sheer chance, but very surprisingly, there are several sets of stills from Sone ki chidiya which you can find on the web, in numbers which I have never seen for any other of her movies!.. Makes one wonder, doesn’t it??!! Here are a few, which of course are very pleasant to look at, but eerily apt to illustrate the film’s paradox.

Some other hilarious scenes show people wanting to appropriate her in a pathetic effort to keep her and they display the best comedic false emotions, hoping the opposite parties will believe them! These emotions, which normally are what connect us to our truthful selves, are here mocked and falsified in the most shameful way:

The only gentle person in this zany household is an uncle, who tries to soften Lakshmi’s plight by dampening the clash between her and the vultures ready to eat her alive, but he’s also a gold seeker! Indeed, the story makes him into an alchemist and he’s seen running away at the beginning of the film from an explosion threatening to blow up the whole building!

Otherwise, Lakshmi is a darling, I’m thinking especially of the moments when she’s shown looking after children, or hoping to look after them, anticipating her life as a mother and family entertainer… She displays an affection and a tenderness which is quite touching:

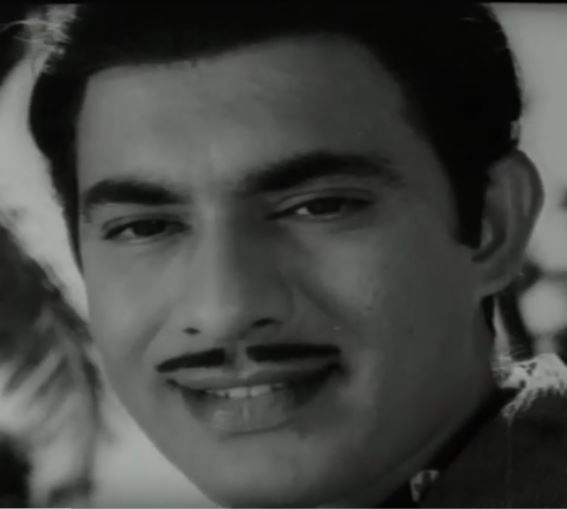

Above is a picture of her face when she hears children being mentioned! Now of course all this is all the more meaningful as Lakshmi is going to be bullied and manipulated in so many insensitive ways. First there’s her adoptive family, as we’ve already said, then the filmi people, who pressurize and utilize her, then there’s her first love (played by Talat* Mehmood, said to be one of the best-looking beaux of the day…):

Unfortunately, he’s not after her, but after her money, and so when he learns that she’s destitute, because all her earnings are in the hands of her “guardians”, he leaves her and the fall is all the more painful. I have managed to capture this picture, below, in which the prince charming is seen fitted with tiger teeth, just visible behind a prim and proper smile :

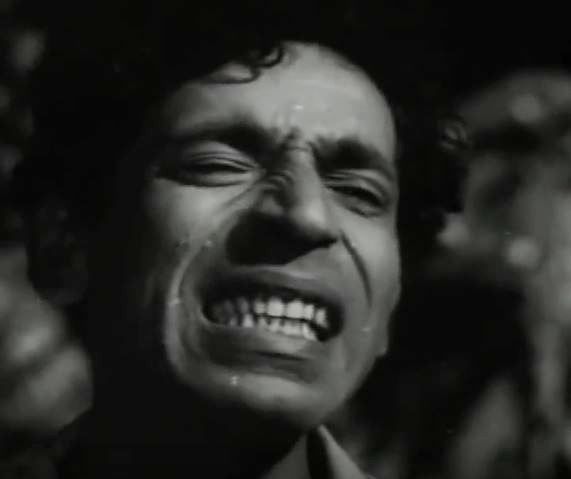

While I’m it, I might as well show you the rest of the gallery of hyenas, jackals and other carrion birds:

(above, the director’s grimace as he tries to understand why he has to redo his scene so many times, and why Lakshmi can’t simply “perform”, whereas she can only act well if she feels well)...

All these faces underline the opposition that exists between the world of purity and truthfulness and the world of shadiness and duplicity. Evil is shown thanks to scowling faces, as it was done in medieval sculptures, along with bored or “worldly-wise” expressions which all serve to show the sadness and disillusion which goes hand in hand with the loss of innocence. Nutan’s expressions, on the other hand, introduce us to the realm of benevolence and grace, which radiates charm and beauty when it is filled with positive feelings:

… but also shows how much beauty and truth can suffer and pale when confronted to harm and injustice:

The moment of truth comes in the end, when Lakshmi is faced with the problem coming from the principle she has been evading until then. After she has been saved from suicide (because of despair at being jilted by Talat) by the handsome and decent Shreekant (Balraj Sahni), the poet she loved in silence, she is tested by him on the very grounds that support her: her love of art, music and beauty. Here, a twist in the scenario is used in order to achieve the test: Shreekant doesn’t know who she is, and what business she’s involved in. For him, even though he acknowledges the necessity of the film industry, women who show themselves on the screen are despicable persons who risk their morality. When he discovers he has been romancing an actress, he recoils from her, and at the same time almost, he’s approached by Lakshmi’s “protectors” who give him money first to work for them as a lyricist and (when he refuses), an even bigger sum to let go of her. Being a socialist (like Ismat Chugtai!), he gives the money towards the foundation of a cinema school, because for him the industry ill-treats impoverished workers who suffer from our spectacle-thirsty society. Now of course, when Lakshmi comes to hear of the deal, she believes he has accepted to be bought away from her, and she starts to swoon at being once again deceived in her affections. All ends well nevertheless because she realizes he’s taken the contract money for the well-being of the poor workers (who will now have the chance to be trained, perhaps, thanks to the cinema school, and earn more), and not for himself.

A pic of the handsome socialist!

But such a (rather complicated) twist is only interesting because its sheds a light on the (also complicated) problem of involvement in the potential duplicity of feelings as shown on the screen. Shreekant represents the position according to which the cinema and other performing arts use the feelings of performers to mimic true ones, and manipulate the spectators’ feelings all the better to pocket their money. Lakshmi represents the more mundane position according to which such a compromise is morally acceptable, and here I think we must connect to Nutan as an actress. It seems to me Nutan represents precisely what the solution to this problem should be. Her career as an actress has been to play her roles to the utmost of her possibilities without forgetting two things:

- the feelings expressed on screen have got to be truthful, and therefore reach the soul of the actor and not just his (or her) surface power of mimicry;

- the spectators should value such shows as exemplify this truthfulness, and reject manipulative or mechanical feelings.

Needless to say that these attitudes have not had much influence on how spectators on the whole have behaved in cinema history! But what it does show is that Nutan had set an example, and Sone ki chidiya dramatizes it: it is possible for women (and for men, naturally) to appear on the screen, emote and still preserve a form of purity and truthfulness which the cinema industry doesn’t really uphold. The trouble is that it does need actors to be truthful, but truthful to their roles as film-directors and producers define them. The difficulty is for actors to recognize when they are being used for roles that steal away their integrity, and this is certainly something Nutan felt keenly. Abandoning this integrity bit by bit often happens because a career is a long process, and the needs for cash always greater… And also it’s just so easy for everyone around those fabulously gorgeous individuals to convince them they are acting well when they fit into the role-models which satisfy producers.

Because Nutan was indeed a fabulously good looking star, and so she corresponded to what producers wanted most: a need to see, and a willingness to pay in order to do so. Nutan provided them with just that. But where she made a difference was how she obliged the viewers to accept that stardom stops at a limit, and that actors must be as transparent as possible for their roles to come out through them, and not screen these roles with their appearances. What was extraordinary with her is that this appearance was precisely what led spectators to go beyond it, towards what was behind it, her soul perhaps, or at any rate her character, the person who was struggling to make the role life-like. Here are some final views of such an effort:

Happy birthday Nutan! (she would've been 82)

* Thanks Madhu for the correction of the name!

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)