Jalsaghar, the music-room of a monomaniac

Publié le 4 Mai 2009

This 1958 film, Satyajit Ray’s fourth, might seem to us, 50 years away from it, a strange and slow vestige of a time when the cinema was sadly deprived of the wizardry we now love so much in it. The narration seems clumsy; the lighting is handicapped by too much or too little contrast; the characters have very little to say or do; even the story seems hackneyed and ordinary: an ageing zamindar, Huzur Biswambhar Roy (Chhabi Biswas), reminiscing about his past glorious life as he used to entertain the classy neighbourhood with quality concerts in his mansion’s Music Room (the Jalsaghar), thus squandering the estate money to the point that he loses all, including wife and child (some of you might like to go to oggsmoggs for a more detailed description of the action, and Upperstall.com has a nice presentation of Ray’s artistry).The historical point is clear too: the landed gentry at the time of the Raj was doomed to give way to a wiser bourgeois class of businessmen who felt which way the wind was blowing, whereas the former remained stuck in their preconception that their decaying privileges were going to last forever. The film tells not only of the passage of time and the attack the new generation carried out on the older one, but of the democratic and technological progress of the XXth century, when vested interests based on gentility and lineage had to give way to a more individualistic society based on work and economic exchange. India passed very quickly from a feudal society to the Industrial era, and the transition has been brutal.

One could focus on the moral dimension of the movie: on the vanity and pride of this selfish, idle profiteer, for whom “money has to be spent”, when it isn’t even his, but his wife’s, and who neglects the duties of protecting his estate against the floods of the nearby river to the extent that, little by little, his lands are dilapidated and become dangerous. The whirlpool, into which his wife and child drown, one stormy night when he and his guests are busy listening to a choice concert, is probably indirectly his own doing (or rather, his own doing nothing). When we see the flat barrenness of the riverbanks outside the huge mansion, a ridiculously large palace compared to the means its owner is finally left with, we understand that they represent the burning emptiness his passion has left in his heart (and what is this shadow on the wall, between Roy and hiswife's portait?)

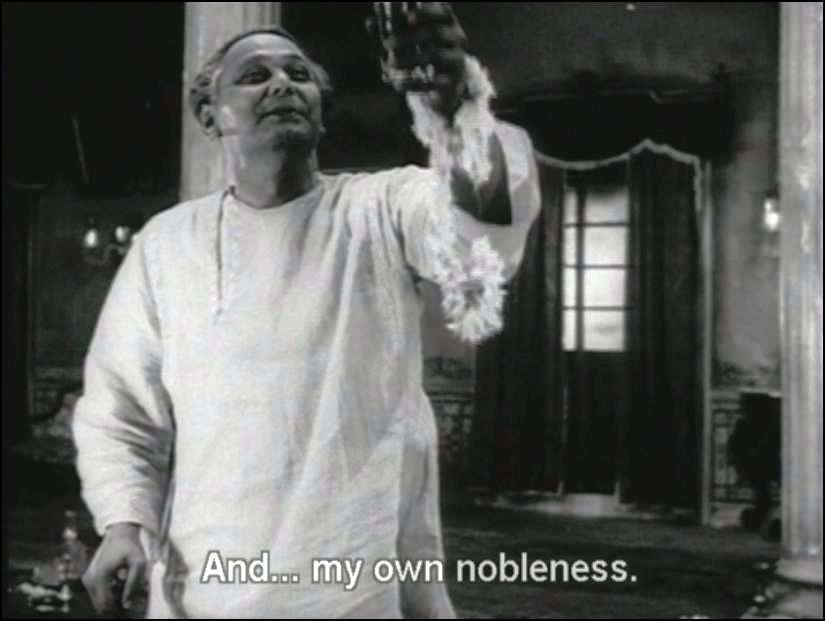

So there we are: Jalsaghar depicts a passion, a spiritual illness, as much as the passing of a social class of landed aristocrats. What we attend to (much like the house’s servants, who see everything, unlike the guests who are fooled by the façade of this grandeur) is the workings of vanity and rivalry. Roy’s place in life, what life means for him, centres around a form of big-heartedness which, up to a certain extent could be called generosity (money is there to be spent, not to be hoarded), but which, manipulated by his passion for superiority and glory (even at this local level), becomes destructive and crazy. After all, what evil does he do? All he does is spend his money to stage concerts in his stately music-room, and have genteel company enjoy them with him. Even if this can be judged as decadent or alienating, one might say that Power has, throughout history, employed its time in far worse ways. Didn’t someone say that beauty will redeem the world?

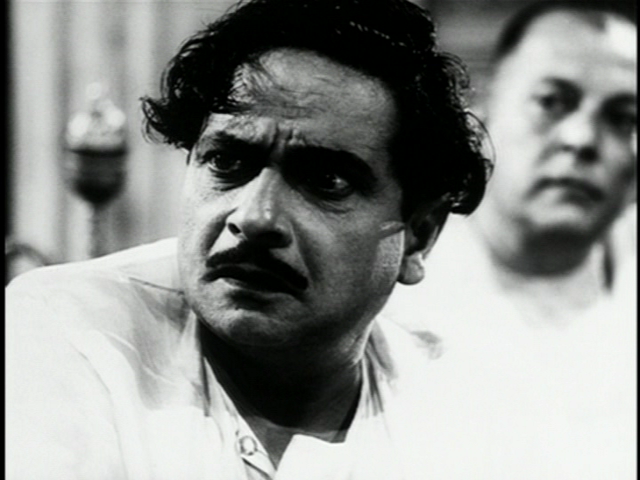

What lies at the core of the zamindar’s passion (and what makes the film the masterpiece people so often say it is, without really explaining why) is the rivalry he feels for his neighbour, the son of the local usurer. Naturally this upstart is first slighted into submission, but he doesn’t seem to resent it, he finds it normal, in fact. At no time do we see Mahim Ganguli (the rival) complain or rebel against his revered neighbour. Instead, the usurer’s son copies him, and, with his slowly mounting fortune, builds a big house, like Roy’s; then he organises the same type of party for his own son’s coming of age; then, later, when he has managed to find space in his house for a music-room, he comes, as he has done for each of the previous events, to invite the old zamindar to witness his growing status and honour. But each time, the same thing happens: Roy turns down the invitation and to the dismay of his butler (who knows where all this is leading) he steals his neighbour’s idea, and pretends that he too has a concert on the same day. Which he then rushes to organise, going as far as paying a higher price for the artists than Ganguli.

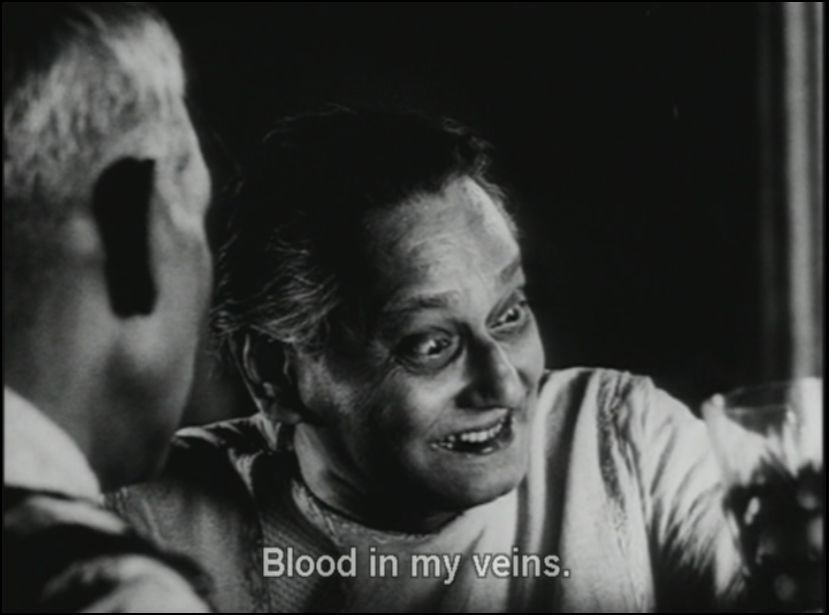

When he is thus engaged in his mimetic competition, he gets a kick, like a shot of adrenaline which can only be explained by the fact that he satisfying a great passion: we see him contentedly walk to and fro on the straightened carpet, under the brightly-lit chandelier, where every candle must have cost a pretty penny, eagerly imagining in his mind’s eye the looks he will be given that night, when, all his guests having arrived, he makes his lordly entrance and is applauded as the prince he has always been. And, when the show is over and they have all gone home, when he is left alone with the dwindling lights and his bottle of liquor, he experiences the withdrawal of a drug addict, and panics, not even noticing that day has come…

What is interesting is the double nature of this rivalry: to experience his high, Roy needs his rival’s mimetic copying of his own behaviour; but he also needs to fight him, to better him and crush him in order to prove to himself that he is the greater. So his rival affirms his delusion by wanting to be like him, and acting that way, and Roy confirms it by refusing the equality which his rival seeks. In other words, Roy acts the grand aristocrat by organising his life according to the envied patterns of nobility, and when this nobility is recognised and flattered, he refuses to share it, all the better to have it envied even more. Of course this spiral of rivalry entraps him and finally kills him. It the end, he is precipitated as much from his horse’s back as from his tiny perilous peak of selfishness where he has absurdly climbed, to be out of the rabble’s reach.

One element which Ray has used to a great purpose, even if it a classic instrument, is that big mirror in the music-room. First its doubling function tells the film’s mimetic story, and, as Roy gazes at his own image, it serves as a multiplying agent, squaring Roy’s equation as his rival’s double. But all around the mirror, the portraits are like multiplied self-visions which, mirror-like, as revealing agents, show the reality he has hidden to himself, a reality which the appearance of the spider shockingly underlines. For when Roy was trying to reinvest his failing grandeur in the wealth of his ancestors’ glory, what he sees on their offspring’s surface is that symbol of splayed out horror: the spider has cracked the picture as much as it has infected it. This spider is his passion.

Passion is destructive, we all know it; at least in theory. But how many people declare that for them passion is all that counts in life? That they cannot do anything if it isn’t out of passion, implying that passion contains a virtue which it is needless to question? (see A suitable boy) Well, Satyajit Ray attacks this myth - as do all moralists of course – but the simplicity of his film, its unity of purpose (one could argue there is only one real character, Roy, in the whole film), its depth of analysis, have a strength which few have equalled perhaps. Art or beauty are never an end in themselves, they never justify a course of action; they can hide a profoundly selfish and ultimately destructive pursuit. After all, who knows whether (with this blog and passion for Indian movies) I’m not a victim of this very symptom I’m describing?!

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)