Parched - Righting women's wrongs

Publié le 2 Mai 2016

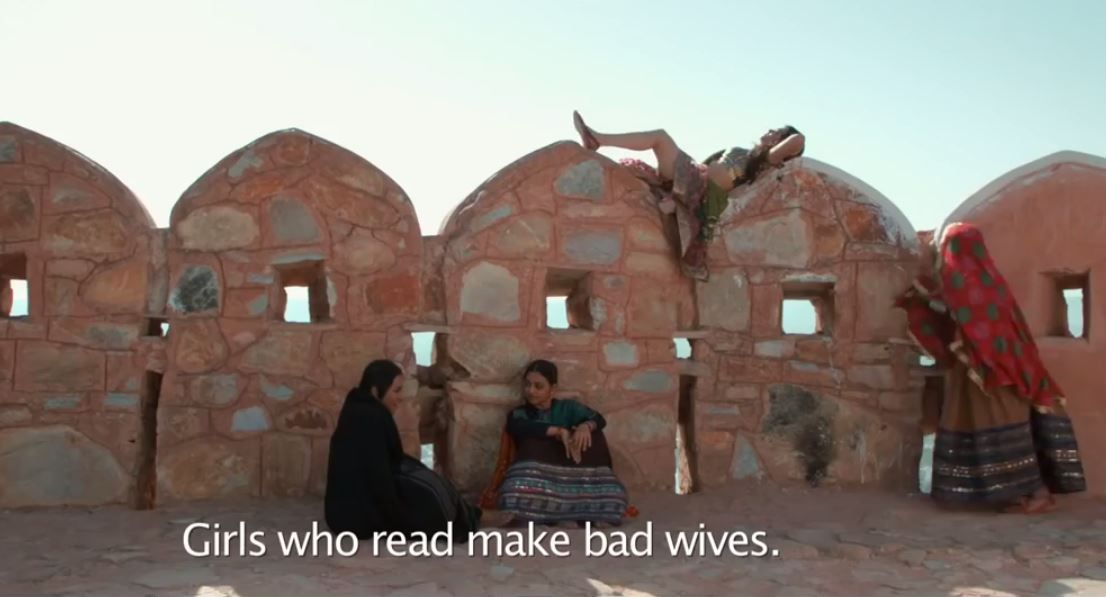

Went to see Parched (2015), by Leena Yadav, of (not good) Shabd fame. So I was a bit wary of what was to come. What came was a rather pleasant surprise, I’m happy to say. Parched is the story of four gujarati women, stuck all four of them in male-dominated prisons of traditions and practices, and they are the film-maker’s chosen figures to denounce the plight of women in rural India, still today. First there’s Bijli (Surveen Chawla, who looks strikingly like Aishwarya Rai), the travelling dancer and prostitute: she’s the only girl to have left the village and in spite of her spunkiness, is as dominated and manipulated as the others. Then Rani (Tannishtha Chatterjee, so great in Brick Lane), a 15 year widow left alone with her 17 year old son, Gulab (Riddhi Sen), more about him soon. Lajjo (Radhika Apte) is another, younger villager who’s married to Manoj (Mahesh Balraj) but cannot have a child and anyway, child or not, is beaten as soon as he sets her eyes on her. Finally there’s Janaki (Lehar Khan), with whom the film begins. She’s fresh out of her village, and has been sold to become Gulab’s wife.

I was interested to read that Leena Yadav actually toured Gujarat in search of people to listen to, and women’s lives to portray. She explains in her interviews that she was the target of macho slurs according to which women like her arriving to film in the villages would do nothing but corrupt the women. She took time to listen to these women, and from their stories, built a film which, if it isn’t totally free of good feelings and some spectator-oriented scenes, certainly does its political and social job. It will remain to be seen how many people in India will see it, though. Let’s get done with the tacky bits first. Number one in the list of compromises, the actresses are all of them beauties: this is fine of course, if one likes beautiful actresses (and one does, doesn’t one?) but highly unrealistic. One can’t help wondering how Lajjo’s mindlessly brutal and drunk husband can see nothing of his amazingly pretty wife, and hits her blindly all day long. Okay, he’s upset because she’s got herself a job with the village entrepreneur, Kishan, who employs women to stitch those beautiful wall hangings. It will make him look like a fool. And supposedly he’s angry at her for not having given him a boy. Of course the assumption is that she’s sterile, and when she learns he might be, instead of her, and finds a way to get pregnant, he’s infuriated by the news.

The sex scenes are another minus, not that there’s much of them, but if the film really was 100% in earnest about social issues, what would be the use of this pandering to the pseudo-aesthetic needs of a voyeuristic spectator? I’ll suppose the film-maker thought they would increase the number of concerned people… But at the same time they do reduce the sharpness of her message. It’s all right that we see the pandemonium scenes where Bijli lights her fire in that male-filled tent of hers: her shows mean a lot in terms of what goes on in the minds of the male population. But this extraordinary meeting in a cave of a desperate Lajjo with a middle-aged stubbled guru… rather cheap, I’d say. Same goes for that moment of “intimacy” between the two lead girls, Rani and Lajjo: it’s understood that men are nothing but aggressive and drunk brutes, find it normal that women are slaves only meant for their service and can be told so. But then why underline that women are the human opposite to such men? Isn’t it only too obvious? I don’t think the movie gains from us viewers (guys or girls) being made to lower our looks to Lajjo’s chest.

It’s a relief there are a number of powerful points in Parched. First Yadav’s courage: it certainly needed pluck to start from nothing but visits to villages and women’s stories and from there write a story which perhaps people will spit on because it’s against the interests of established macho conventions, or even look down on as one more feminist rant. Then there’s the girls’ energetic friendship, which works a little like a feel-good family, but it’s pleasant to watch and it lifts your spirits : we come out of the film feeling that not everything is lost, that they’re strong enough to resist this blocked society, and flee. To say the truth, I’m not sure how realistic this is, even today. Could a married girl run away from her village and hope to get lost in Delhi without, sooner or later, being found out by some brother or cousin, on a mission from the family or the panchayat, and ruthlessly brought back where she belongs? What real chance does she have? Can this film be anything else but a feelgood story? Can it contribute to changing dowry practices? Can it make more village girls learn how to read and continue to higher education before getting married against their will? Let’s hope Leena Yadav has chosen the right mix.

Another good point is Gulab, Rani’s boy who gets married at the beginning of the movie to Janaki, bought as we said by the widow on borrowed money. He seems such a sickening jerk that I believe his point will be made, or at least I hope. If only a few guys watching the film learnt enough from his moronic arrogance to change a few things in how they educate their boys, well then it would be a victory. What’s particularly well done with Gulab is that he’s exactly in the middle of boyhood and manhood, or rather he’s monstrously a male in a boy’s body. This rural society declares young boys married men at 17 when they should be at school busy about history and maths. And by declaring them men at that age, by buying them a high-cost teenager which the whole community has been busy about for months, they give them the right to lord it around as if they were the conquerors of the world. Whereas it all boils down to them being helplessly enslaved to their sexual and drug-enhanced clan conventionality. Sickening and frighteningly effective.

I should add to the list of trumps the presence of a foreign-looking woman in the village (not sure if she’s Sayani Gupta), the wife of the entrepreneur mentioned earlier who by the way gets absurdly attacked by the bunch of moronic bored youths (led by Gulab) for being successful. Anyway what’s good about her is that she represents first educated women and the fact that such closed-up communities are in dire need of opening up to other influences than themselves. Her slightly different features (Asian) are a source of rude comments from the elders, by the way, whereas the film heroines appreciate her and love her fairer skin. But this phenomenon of the half-stranger raises the question of the importance for groups to welcome elements which will enable them to look at themselves and their practices with a less self-indulgent eye, or at any rate with a less culturally satisfied judgement. Because the argument can always be: if we’d been left alone, no crisis would have occurred. We know this is a sham.

So yes, watch the film; Gujarat’s old stones and prettified desert look great on screen, the rajasthani colors flash as bright as they used to do in Paheli, and women’s jewels shine and mesmerize. It’s not completely activist cinema in the sense that Yadav has here and there given us more to see than to think, or at least, has thought that what people see might be shaped not only by reality but by the spectators’ needs. Her message to women and men alike, to village elders, and to educators, most importantly, needs to be heard irrespective of these failings.

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)