Yash Chopra, the power of Passion

Publié le 25 Octobre 2012

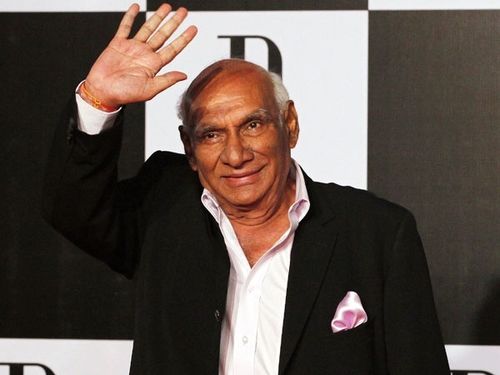

Yash Chopra passed today; because of the importance of the guy, I decided to post this eulogy of him written some time ago, but which I still feel is appropriate.

Yash Chopra… Say this name and immediately vast landscapes appear, green slopes where lovers mirror their gaze in the other’s eyes, enchanting music lifts up a crowd of spring birds, dark men march towards their destiny, violence smoulders in the heart, suffering mothers obey their dharma, and love reigns supreme in spite of all odds. Mr Chopra’s reputation as an incurable romantic is so ingrained that it’s difficult to start with something very different! You might as well adore him or hate him, in fact. YC is Bollywood at its best, or at its worst. And love, melodrama… with so banal a theme, such a typically Bollywoodian feature, why does the man stand out? Where does the legend (and the money) come from?

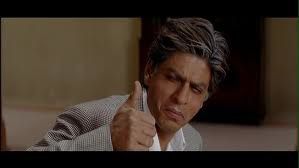

What’s interesting in his profile is the relatively limited number of films, and the stupendous number of blockbusters. This Indian director, born in 1932, has done only 21 movies? How come such a sparse output – yet over such a long timespan - has been so successful? I know of a few other such directors, Stanley Kubrick, for example. But Indian film directors? In the prolific Bollywood culture, there can’t be that many. Yash Chopra has the rare gift of making a landmark film out of every opus he directs, or nearly. One might say he’s managed to find the mix of story and spectacle his audience was ready for. One might add he’s got that skill to be as true and evocative with social-political films as well as with love movies. He’s also associated with the greatest actors of the moment, mainly Amitabh Bachchan and Shahrukh Khan for the men; and Sridevi, Rekha, Waheeda Rehman, Madhuri Dixit, among others, for the ladies. I would also add that he’s associated with the greatest musicians, Sanjeev Kholi, Hariprasad Chaurasia and ShivKumar Sharma, notably.

All this would be true. But I think it’s basically a knack for passionate stories. Stories that work. Yash Chopra knows how to exploit and tell stories in such a way that he meets the public that’s here to appreciate them. Good stories that are going to be successful need to deal with people’s main interests in life: the passions and desires which everybody feels or wants to feel. Rebellion and courage, virtue and sacrifice, love and duty. And the romantic dimension is perhaps not so much in the privileged choice of love – even though one can’t deny the place of that type of story – but in the intensity of the passions shown to transform the protagonists’ lives. Passion: does that word summarise Yash Chopra? Idlebain.com (here) says that “tradition” is a very important determination with Yash Chopra. Passion can of course be traditional, and dealt with in a traditional way. The author of that review contends that Lamhe (1991) was his only iconoclastic film. Having not seen all YC’s movies, I couldn’t say he’s wrong, but somehow tradition carries a certain conservatism which doesn’t exactly fit with passion. There is a violence and a revolutionary spirit in passion which doesn’t care about tradition. Yash Chopra has successfully innovated in ways that might have helped define tradition (that’s his classicism), but certainly he’s recreated this tradition to the point of challenging it.

He’s not a total inventor. No artist ever is, in fact. In order to be judged innovative (hip and trendy are qualifications you often read concerning YC), you have to understand the traditions, and depart from them: do something sufficiently powerful that will redefine them and set a style which others will in turn take as a basis. So if for example, Deewar takes up the “angry young man” theme from Prakash Mehra’s Zanjeer (1973), Yash Chopra has created a trendsetter which critics don’t attribute to his forerunner. I haven’t seen any other Bollywood mine-films, but certainly Kaala Patthar has the depth and guts of any competitor.

Sometimes his stories are artificial to the point of straining the belief of his spectators: Darr deals with such an obsessive lover that one wonders if they really exist in real life. And In Lamhe, the basis of the plot is very thin: you have to accept that a daughter can look exactly like her mother to make the story credible: a very rare situation, I’d say. Coincidences occur rather frequently in YC’s cinema, and I’d say, they’re often romantic coincidences, which are only one type of coincidence. A coincidence is in itself rare (otherwise it wouldn’t attract attention to itself that much), so a romantic one… But I think the director couldn’t car less. What he’s doing is using a plot, perhaps artificially created to work under the circumstances, and draw on the potential created by that plot. He doesn’t hesitate to add meaning thanks to coincidences which elevate the story to the level of myth, or legend. Veer’s prisoner number (786) in Veer-Zaara (it’s also Vijay’s dockworker plate number In Deewar) is an example everyone has noticed. It’s Allah’s holy number, and the film is about the need to unite Muslims and Hindus.

In stories of passion, says the director, anything can happen. It’s like tragedy, or mythology: we are no longer really in the everyday reality (movie-goers don’t mind suspending their disbelief we know that): passion justifies a level of experience which has its own uniqueness. Symbols flare up in such stories, whereas in realty, you’d probably have to draw other people’s attention to them, and to you, the decipherer. On this blog I’ve developed the symbol of water in Kaala Patthar: making a film enables you to weave together bits and pieces of experience and occurrences in such a way that the meaning it displays will depend on that assortment. Yash Chopra knows how to do that task with particular skill. His choice of characters, drawing from world myths and legends give his best films an interest and a lasting effect. So if he forgets that dimension, he quickly becomes manipulated by the fickleness of passing taste. For me, that’s what happened with Dil to pagal hai.

There is another structural element which YC implements in his best movies. Let’s let him explain:

"Relationships interest me because man is one creature who is capable of sane as well as insane behaviour. It's this nature of human beings that inspires and gives room for innumerable plots. Like in Daag (1973), Raakhee, who played the other woman, created all the drama, as did Rekha in Silsila (1981). In Aaina (1993) it was the jealous sister while in Darr (1993) it was the obsessive lover. So unlike other movies where a villain is added to create the problems, in my films villainy is substituted by a third angle." (reference)

Ah, here’s something Bollywood has to learn from the master: “a third angle”. I have in effect rarely seen mainstream Bollywood movies adopt that technique. Of course many Indian films have, but they were often socially oriented, fringe-type movies. Yash Chopra has succeeded in bringing this third angle into commercial hits. What’s a third angle? It’s a pole of interest which is neither good or evil, black or white, and is sufficiently developed to tilt the standard Manichaeism towards or more all-encompassing rendition of human experience. In Deewar, for instance, the third angle is Vijay’s swerving (and therefore very human) fight to reach self-justification. In Darr, it’s the unclassifiable obsession of the crazy lover. In Kaala Patthar, it could be Mangal’s course from utter villainy to sacrifice. All these diversions from easily identifiable Good & Evil create a third angle which adds the depth and the richness to the best of YC’s movies. And this notwithstanding a hero structure which is more three-polar and dual. Veer-Zaara gives us perhaps the best example of this structure. Not only do we really have three essential characters (Veer, Zaara, and Saamiya), but these characters are themselves included in a wider generational structure where elders shape the role and life of their “descendants”. The third angle, brilliantly personified by Rani Mukherjee’s woman lawyer character introduces a last item of reflection which Yash Chopra’s films have been recognised for.

Indeed, despite the formidable stature which YC possesses today, he has not always seemed recommendable and acceptable to all publics. We’ve already alluded to that commentator who declared Lamhe iconoclastic, because of the supposedly incestual nature of the main love concern. But that commentator has forgotten that Deewar was deemed as scandalous when it came out. The famous scenes including Amitabh and Parveen Babi in bed, for example. But Vijay’s character itself must have been difficult to deal with: he’s a vindicator of rights who turns bad, a victim as well as a perverted hero. And seen from a certain westernised angle, Yash Chopra’s stance in Veer-Zaara to reconcile India and Pakistan is politically-correct; but I wonder if all Indians agree. Finally, his decision to impersonate in Pooja (from Lamhe) a free woman who does not care about the possible incestuous undertones of her love interest was brave indeed given the financial costs of a YC film. So Tradition is not that welcome in his films, as we can see. Yash Chopra is more a maker of traditions than a follower. And yet he remains mainstream, he is recognised as one of the reigning kings of the masala type. No little feat.

And here's the ever-favourite song from Veer-Zaara, dedicated "to you" Yash Chopra:

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)