Sagina: a freedom beyond politics

Publié le 7 Décembre 2009

Sagina (1974), a hindi remake of the bengali Sagina Mahato, shot by the same director (Tapan Sinha) four years before, is a reflexion on work exploitation, oppression and revolution. The story is set in the “tea gardens” of North-East India, in the forties, and centres around the charismatic figure of a local worker, Sagina Mahato (Dilip Kumar), who is the acknowledged leader of the exploited bunch of mountain villagers toiling away for the benefit of the British. As expected, the capitalistic manager is a ruthless heartless racist, whereas Sagina, who has the guts to confront the boss, manages to make him understand that the coolies are human and cannot be simply beaten and used like cattle.

Sagina’s fiery character is doubled by that of Lalita (Saira Banu), a mountain Bengal tigress ready to slit whoever approaches her, and whose faithfulness to Sagina is one of the movie’s great wonders. Because Saira Banu isn’t a the movie’s pretty face: that title is reserved to Vishaka, the socialist secretary we shall speak about in a minute, played by beauty Aparna Sen. But to have cast Saira Banu as Sagina’s companion (we don’t know if they’re married, but it can be supposed) shows a sure flair. The movie’s realism and authenticity certainly gains from it.

Sagina’s fiery character is doubled by that of Lalita (Saira Banu), a mountain Bengal tigress ready to slit whoever approaches her, and whose faithfulness to Sagina is one of the movie’s great wonders. Because Saira Banu isn’t a the movie’s pretty face: that title is reserved to Vishaka, the socialist secretary we shall speak about in a minute, played by beauty Aparna Sen. But to have cast Saira Banu as Sagina’s companion (we don’t know if they’re married, but it can be supposed) shows a sure flair. The movie’s realism and authenticity certainly gains from it.

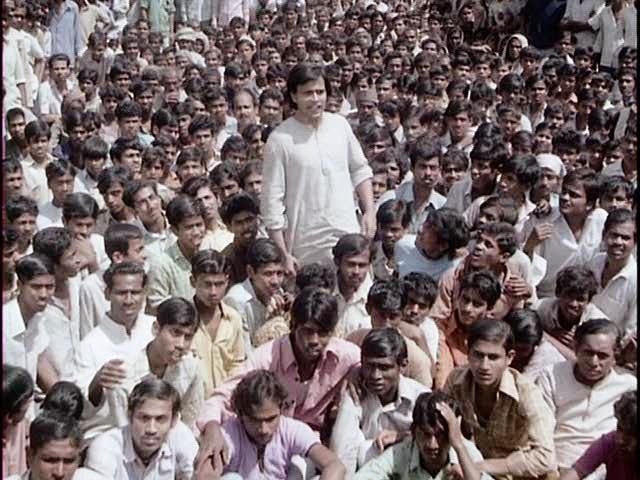

To say the truth, it also gains from Dilip Kumar’s personality. The “king of tragedy” cuts a fine role as a cunning country labourer, alternatively as peculiar and unsexy as possible, and then just as hilarious and witty. He manages his pathos with consummate art, knows when to play the fool to avoid hero-worship, and when to stop for the spectator to grasp the tragedy of the cause. His antics with Lalita are really what befriends him to us: together they’re a great couple, full of temper and pride, and these are based not on a selfish desire to ensnare the other into a private relationship, but their love builds the community, and testifies to its lively spirit. For instance in the scene where a young Indian girl has been raped by a white employee from the company, who gets caught and Sagina declares revenge, at the window Lalita watches him go, and, as she holds the frightened girl in her arms, she breathes in the fantastic breath of victory and confidence in the man who is such a naturally fearless leader.

To say the truth, it also gains from Dilip Kumar’s personality. The “king of tragedy” cuts a fine role as a cunning country labourer, alternatively as peculiar and unsexy as possible, and then just as hilarious and witty. He manages his pathos with consummate art, knows when to play the fool to avoid hero-worship, and when to stop for the spectator to grasp the tragedy of the cause. His antics with Lalita are really what befriends him to us: together they’re a great couple, full of temper and pride, and these are based not on a selfish desire to ensnare the other into a private relationship, but their love builds the community, and testifies to its lively spirit. For instance in the scene where a young Indian girl has been raped by a white employee from the company, who gets caught and Sagina declares revenge, at the window Lalita watches him go, and, as she holds the frightened girl in her arms, she breathes in the fantastic breath of victory and confidence in the man who is such a naturally fearless leader.

Things start deteriorating nevertheless when revolutionaries from the city (nearby Calcutta) start becoming interested in the particular worker resistance that has coalesced around Sagina. Such a feat cannot remain unexploited: the communist party who probably is also trying to federate some reaction against the colonial power, comes to the company in the form of Amal, who ventures to put some socialist ideas about rules and legality in Sagina’s mind. Act legal, become a recognised party: that is Amal’s creed. But Sagina, even if he tries to do his best, remains a political yokel, and when a crisis comes, will follow nothing but his instinct. The workers he leads remain unruled and wild, as the Bengal tiger who leads them.

Things start deteriorating nevertheless when revolutionaries from the city (nearby Calcutta) start becoming interested in the particular worker resistance that has coalesced around Sagina. Such a feat cannot remain unexploited: the communist party who probably is also trying to federate some reaction against the colonial power, comes to the company in the form of Amal, who ventures to put some socialist ideas about rules and legality in Sagina’s mind. Act legal, become a recognised party: that is Amal’s creed. But Sagina, even if he tries to do his best, remains a political yokel, and when a crisis comes, will follow nothing but his instinct. The workers he leads remain unruled and wild, as the Bengal tiger who leads them.

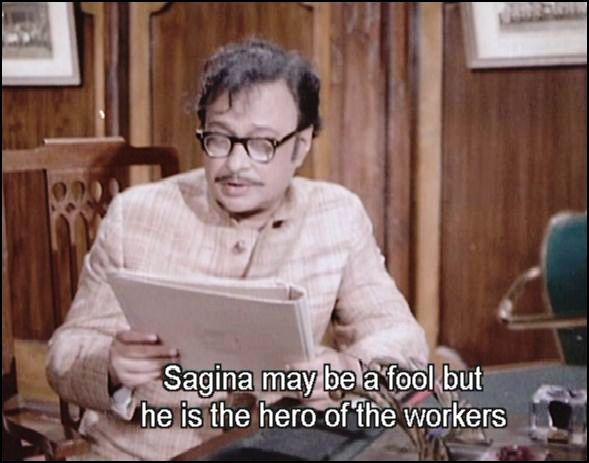

This prompts a second step, and Amal’s party superiors arrive, together with the apparatchika, the party secretary, Vishaka, who incidentally is the daughter of the Calcutta-based owner of the whole industry of which our little mountain unit if only a regional branch. Vishaka is the archetype of the idealist, and we see her father ponder the fact that she has preferred the communist party to her own family. But according to her, it’s because her parents have been absent from her life, the father working, the mother partying. So in a way, she’s the embodiment of criticism against a certain form of Indian colonial profiteering, where the rich upper classes took advantage of what the British needed, a superior-minded class of collaborationists who would help them maintain their stronghold on the dominion.

This prompts a second step, and Amal’s party superiors arrive, together with the apparatchika, the party secretary, Vishaka, who incidentally is the daughter of the Calcutta-based owner of the whole industry of which our little mountain unit if only a regional branch. Vishaka is the archetype of the idealist, and we see her father ponder the fact that she has preferred the communist party to her own family. But according to her, it’s because her parents have been absent from her life, the father working, the mother partying. So in a way, she’s the embodiment of criticism against a certain form of Indian colonial profiteering, where the rich upper classes took advantage of what the British needed, a superior-minded class of collaborationists who would help them maintain their stronghold on the dominion.

The tragic irony of the following scenes is that the communist party boss, Aniruddha, is going to team up with the capitalistic British manager against the untameable Sagina. They jointly organise his election as “welfare officer”, an honour which in effect sends him away to the city where he will be out of the way for the party to set up its own rule with the supposedly prepared workers. Strike is soon declared against the company owners, and the workers, headless, obey their new masters. What happens next is the normal consequence: when Sagina comes back to the village, having understood he’s been trapped into leaving, his departure is thrown into his face as a betrayal: nobody wants to see him any more. The workers are starving and nobody is helping them; the commies are as ruthless as the company manager! Sagina, their chief, their tiger, is back too late: they have lost trust in him. He can go back where he comes from, his former fellowmen are blinded by grief and oppression. Only Lalita, who at first escapes him too (she has not completely groundless reasons to believe her lion has succumbed to the cool charm of the fair apparatchika!), finally falls in his arms and sides by him, explaining everything to him. He then tries to speak to the assembly of workers, but they boo him and, rushing to wards him, trample him mercilessly.

The tragic irony of the following scenes is that the communist party boss, Aniruddha, is going to team up with the capitalistic British manager against the untameable Sagina. They jointly organise his election as “welfare officer”, an honour which in effect sends him away to the city where he will be out of the way for the party to set up its own rule with the supposedly prepared workers. Strike is soon declared against the company owners, and the workers, headless, obey their new masters. What happens next is the normal consequence: when Sagina comes back to the village, having understood he’s been trapped into leaving, his departure is thrown into his face as a betrayal: nobody wants to see him any more. The workers are starving and nobody is helping them; the commies are as ruthless as the company manager! Sagina, their chief, their tiger, is back too late: they have lost trust in him. He can go back where he comes from, his former fellowmen are blinded by grief and oppression. Only Lalita, who at first escapes him too (she has not completely groundless reasons to believe her lion has succumbed to the cool charm of the fair apparatchika!), finally falls in his arms and sides by him, explaining everything to him. He then tries to speak to the assembly of workers, but they boo him and, rushing to wards him, trample him mercilessly.

The last step is Sagina’s arrest at night. The communists have staged an emergency trial in the forest in order to trap him and continue their totalitarian application of their revolutionary theory. All the inhabitants are summoned in the woods, and the revolutionary leader hopes to stage a swift and efficient condemnation. Doesn’t everybody hate Sagina now? Doesn’t every single former friend look upon him as a damned traitor, who has sided with the oppressor? Well, the trial begins and the protagonists start remembering… And this is where the film’s structure comes in, because in fact it opens with the trial, and the flashbacks, which tell all the story, are individual recollections of each of the main actors of the drama: we relive the beginning of Sagina’s epic through their eyes, so to speak, and this all forms the complete story which comes to an end in the woods that night.

The last step is Sagina’s arrest at night. The communists have staged an emergency trial in the forest in order to trap him and continue their totalitarian application of their revolutionary theory. All the inhabitants are summoned in the woods, and the revolutionary leader hopes to stage a swift and efficient condemnation. Doesn’t everybody hate Sagina now? Doesn’t every single former friend look upon him as a damned traitor, who has sided with the oppressor? Well, the trial begins and the protagonists start remembering… And this is where the film’s structure comes in, because in fact it opens with the trial, and the flashbacks, which tell all the story, are individual recollections of each of the main actors of the drama: we relive the beginning of Sagina’s epic through their eyes, so to speak, and this all forms the complete story which comes to an end in the woods that night.

And in fact, slowly, one by one, they refuse to play Aniruddha’s hunting game: at first they’re struck by the scene, but recovering their senses, they realize that Sagina has also been trapped, as they have been trapped. He hasn’t betrayed them, nor is he all-powerful, he’s just one of them. Darker forces had tried to hypnotize all of them into believing Sagina was a double-dealer. Now even Amal loyally recognizes that Sagina cannot be the monster Aniruddha portrays and, cornered, tries to judge all on his own, declaring him guilty and that he should be killed straight away. He has a gun, and is going to execute his crazy justice, but Amal intervenes, and takes the shot. Aniruddha tries to escape, is caught by a vengeful Sagina, who throws away the gun: his hands are enough. But then another executioner enters the scene and ends the madman’s life.

And in fact, slowly, one by one, they refuse to play Aniruddha’s hunting game: at first they’re struck by the scene, but recovering their senses, they realize that Sagina has also been trapped, as they have been trapped. He hasn’t betrayed them, nor is he all-powerful, he’s just one of them. Darker forces had tried to hypnotize all of them into believing Sagina was a double-dealer. Now even Amal loyally recognizes that Sagina cannot be the monster Aniruddha portrays and, cornered, tries to judge all on his own, declaring him guilty and that he should be killed straight away. He has a gun, and is going to execute his crazy justice, but Amal intervenes, and takes the shot. Aniruddha tries to escape, is caught by a vengeful Sagina, who throws away the gun: his hands are enough. But then another executioner enters the scene and ends the madman’s life.

What is very original in this movie is its complex treatment of the forces of good and evil, when an overwhelming number of movies simplify the opposition to a pitifully weak antagonism. Okay, the communist leader is a caricature. But he’s the only one. All the actors in the drama have virtues and merits, alongside with shortcomings and prejudices. Sagina for example isn’t the hero whom everybody loves at first sight. If you identify with him, it is because you understand precisely that he’s limited and ridiculous, and that this is his nature. And this works also for his attitude concerning political action. This attitude has nothing you can tie it down to. It isn’t revolutionary; it isn’t theoretical, it isn’t even political. He fights with his instinct, his courage and his magnanimity. When he senses his community is wronged, he displays a formidable flair for the right words to say to the right person, the right thing to do and when to do it, and this opportunism is his strength. His keen sense of justice and human dignity works miracles among the people he knows, and of course his enemies understand that, who send him away in order to cut him away from his zone of influence.

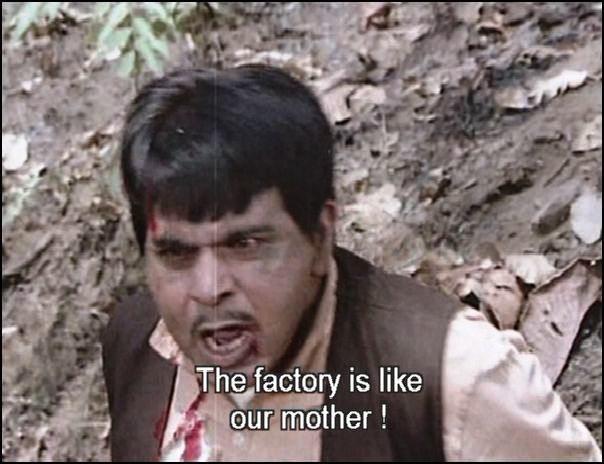

Sagina therefore demonstrates the limits of political science, which is commonly based on the opposition of binary systems: rightists vs. leftists, conservatives vs. revolutionaries, capitalism vs. communism, etc. Both the company bosses, who ruthlessly exploit the workers, and the communist revolutionaries, who come to the Tea Gardens to organise their revolt, are formatted by these antagonistic pairs of opposites. Both believe in imposing their rigid frame of understanding to human labour, and both fail because they don’t understand the human factor, which is made of need, hope and self-respect. Workers are human beings who suffer when exploited (that’s the communist perspective), but also recognize the company as their “mother” (that’s the patriarchal industrialist’s model, which communists will deride as oppressive). Sagina Mahato represents a political force that theorists cannot place in their rigid grid; his freedom represents a third type of interpretation, more complex, more human too. At one moment, the communist leader tells him that orders oblige him to do something. But says Sagina, I don’t obey orders. If you request, on the other hand, it’s another matter. His political practice bases itself on confidence and respect.

Sagina therefore demonstrates the limits of political science, which is commonly based on the opposition of binary systems: rightists vs. leftists, conservatives vs. revolutionaries, capitalism vs. communism, etc. Both the company bosses, who ruthlessly exploit the workers, and the communist revolutionaries, who come to the Tea Gardens to organise their revolt, are formatted by these antagonistic pairs of opposites. Both believe in imposing their rigid frame of understanding to human labour, and both fail because they don’t understand the human factor, which is made of need, hope and self-respect. Workers are human beings who suffer when exploited (that’s the communist perspective), but also recognize the company as their “mother” (that’s the patriarchal industrialist’s model, which communists will deride as oppressive). Sagina Mahato represents a political force that theorists cannot place in their rigid grid; his freedom represents a third type of interpretation, more complex, more human too. At one moment, the communist leader tells him that orders oblige him to do something. But says Sagina, I don’t obey orders. If you request, on the other hand, it’s another matter. His political practice bases itself on confidence and respect.

Of course, you might say that such a political attitude is limited in scope and efficiency. If you want to make things move on a greater scale, that of a country, for example, or that of nations, you have to revert to party discipline and follow orders. Outside the community where he is known and appreciated, what is Sagina’s stance worth? Well, perhaps this isn’t true: Gandhi has shown the world that the dualist politics based on the violence of conflicting interests might not always be the rule; alternating right and left parties are not necessarily the only way to practice politics. A great deal of strength is surely needed to go beyond commonly accepted practices, but they aren’t necessarily doomed. The trouble is that people come to public affairs with these structures in their minds: which party shall I join, which party will give me the best chances to fulfil my interests? Even idealists opt for one side, and believe that if you want to win elections, you have to control a party. Saginas are rare today. But the film’s lesson is that they can and must exist, that politics shouldn’t be left to politicians only. We know it, but how do we act in order to make this change?

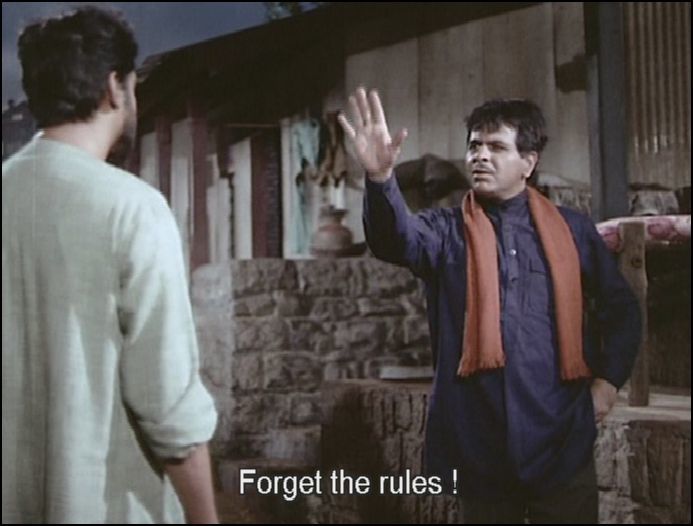

One other theme in the movie, which is connected to the preceding one, is the questioning of rules as the media through which human relations must be established. Amal tells Sagina to act legally, and the latter tells him to “forget the rules”! (top photo)It isn’t enough to say that rules are made for men and not men for the rules; some rules can be changed, some rules are bad, but the concept of rules itself must also sometimes be questioned. The law guarantees that people will live in peace, normally. But sometimes is creates war, because the law has become the expression of the oppressive power of the rich and the great. They uphold the law as a means to continue their rule and protect their interests. So the law must regularly be re-evaluated by another law, that of “humanity” (whatever that is – it depends partly on which human community is concerned), the law which is inside all of us, and serves as the ultimate standard. Sagina represents also that final recourse, a fragile one, as the movie shows, because it can be manipulated (hence the need for education – Sagina is illiterate), but an indispensable stay against the perversion of the law.

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)