Shatranj ke Khilari, ode to a lost kingdom

Publié le 28 Décembre 2009

Shatranj ke Khilari (1977, The chess players) shows how close Satyajit Ray has come to Shakespearian inspiration. In this story of two gentlemen of Lucknow we have the dilemma of the good king, made powerless by a power stronger than his own; we have the Realpolitik of History and Conquest magnified to the dimension of lyrical drama, we have - on the backdrop of a nostalgic XIXth century society of servants and breathtaking outdoor scenery - the subplot of loud-spoken and often clownish compeers who bring their conventional comic relief. The two stories intertwine superbly, and create a rich pattern of symbolical and psychological truth which deserves the greatest praise. I think only Satyajit Ray could pull this off, in Indian cinema.

There have been a number of “chess films” and books, too – Ray’s film is in fact based on a story by Munshi Premchand – notably Stefan Zweig’s Schachnovelle, and the game’s inspirational symmetrical structure contains a sort of magnetism which is easily used visually and dramatically. But Satyajit Ray isn’t a victim of that influence; the game’s charm, or its curse, doesn’t interest him: he plays with its evocative tradition of confrontation and isolated pair of opponents, and is as much interested in the players as in the game. Chess is only an image for the main subject of the film, the conflict of power opposing the various protagonists. It is thus possible to decide that the main characters are the title-bearers, i.e., the two noblemen with their quirkiness and their aloofness from outside events, or the king, his prime minister and General Outram, the British Resident in Lucknow (Richard Attenborough). Depending on whether you think the first are Ray’s target, you have the perspective according to which the film criticises the moral futility of the gentility, its indifference to the real world. Or your point of view would be a more political and historical one, and you would say that the film dissects the weakness of Indian resistance to British imperialism.

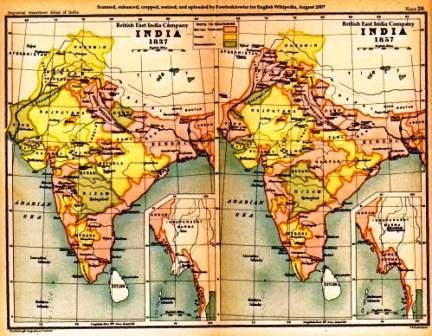

I have decided to choose the second one, for several reasons. I realize that the film isn’t called “The powerless king”, or “How Britain ate the last cherry on the Indian cake”. But I’ll explain this later. First there is Satyajit Ray’s choice of language. Shatranj ki khilari is his only film in urdu. We know that otherwise he writes and directs his film in Bengali. Choosing urdu means that he is placing himself in the centre of the political and historical chessboard, where the roots of modern India are to be found. How did England become a colonial Empire? What were its moves to achieve that aim? Everything started in Bengal, around Calcutta. But things really became serious when the imperialist power began conquering the subcontinent in a pincers-like movement, South towards Madras and North towards Delhi, thus preparing for the moment when the two claws would meet in Bombay, as you can see on this double map of India.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/6/61/India1837to1857.jpg

The encircling is done in 1857, one year after the annexation of the kingdom of Awadh (or Oudh) which occurred in 1856. And 1857 is the year of the famous Indian Rebellion, which marks the end of any Indian claim to supremacy. The Sepoy mutiny takes place in Lucknow, and if Ray chooses to film the event of the dethronement of the king of Awadh in 1856, it is in natural reference to the events of a year later. The strategic moves which would enable Britain (through its commercial cover-up, the East Indian Company) to rule all of India as from 1857, were prepared by the careful planning of the 1856 coup.

So making the characters speak Urdu emphasizes for Ray the centrality of Awadh as an essential square on the political and military chessboard. Just as Lucknow was the centre for refinement and culture at the time (and Urdu its linguistic medium), Awadh was the central and remaining link in Britain’s conquest of the Northern states. It had to be subjugated, and even if the move provoked the Sepoy rebellion of 1857 (which showed the importance of the tactical decision), the British had already gained too much power for a divided and multiple resistance to come back to the old Mughal Empire. The Government of India Act, voted in Parliament in 1858, instituted the new era of the British Raj which would last until 1947.

(A slice of Oudh, your Excellency?)

So “the chess players” are really Lord Dalhousie and General Outram on the one hand, and king Walid and his ministers on the other. The trouble is that the Indians play in their “Indian” way whereas the English have adopted a “faster” variation of the game. On the English chessboard the Queen has all the power (that’s Queen Victoria of course), whereas the Indian version has only a “minister”. The soldier pawns move at double speed too: two squares instead of one! Finally, the rule of promotion of the pawn into a queen, once it reaches the eighth square is a clear reference to the “conquer and rule” policy. These details of the chess game, explained in the film by the delightful character of Nandlal Sahab, only serve to underline the British expansionist superiority that India could do nothing against at the time. The film also carefully presents General Outram’s conflict of duties, forced as he was to implement the Governor’s decision to annex Oudh, and this gives us a fine psychological insight into the understanding of the broader historical picture.

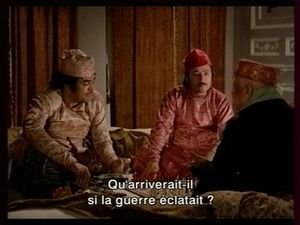

("Do they find our game too slow?")

As a result, the two noblemen Mir (Saeed Jaffrey) and Mirza (Sanjeev Kumar) engrossed in their “stupid” game (as Khurshid, Mirza’s wife – a fiery Shabana Azmi -, says) serve as an comical illustration of the tragic History that engulfs them. They play chess, but mainly they play, while others are involved in the serious job of designing the future of their country above their heads. They are children who do not understand what is happening in the adult’s world. Their “order” is based on the simple rules established by their ancestors long ago, and they have not learned to observe the changing times. And the catastrophe is that the king Wajid Ali Shah (Amjad Khan) is one of these children too! He is shown as a pensive introvert who realises he’s not up to the task of governing, but cannot change that. His character is beautiful and poignant at the same time.

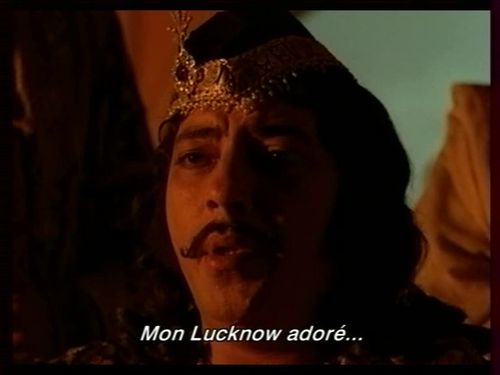

When he is asked to give his order for an army and artillery to be summoned to retaliate the Company’s advances, we see him heave a sigh, as if he was going to cry, look away ahead of him – a view of the palace rooftops appears for a moment in the sunset - and, to the dismay of his ministers, he starts a song about his beloved Lucknow that he doesn’t know how he will be able to leave: “You can take away my crown, but you cannot take away my dignity…” We know that King Walid is known to be a revivalist of the classical arts: “He is hailed as one of the most prodigious promoters of Thumri (A form of classical music) and Kathak (A popular form of classical dance from northern India). In this paradoxical character, Amjad portrays the masculinity of a King and effeminacy of a man dedicated to dance, poetry and music, with equal conviction. Music of the movie is also a plus. In most of the scenes, one can listen to melodious thumris or other compositions of Indian classical music being played in the background.” (Kandarp Mehta from IMdB)

This reviewer has an axe to grind, by the way. He criticises Ray for not being faithful to Premchand’s story. Here is his main criticism: “the biggest alteration has been made in the climax of the story and this destroys the very patriotic essence of the story. In the original story, both the characters, Mirza and Mir, end up killing each other. Munshi Premchand very categorically mentions twice that they did not lack 'personal valor' but didn't want to use qualities of courage and bravery for their nation. Munshi Premchand was a patriotic writer. He wanted to show that prosperity made the Indian elite lazy, myopic and lackadaisical, and fated India with foreign rule. On the other hand, Ray kept them alive, and actually portrays them as impotent people, who accept their cowardice as a fact of life. New York Times Review of the movie (DT: May 17, 1978) wrote Ray Satirizes Indian Nobility: Civilized Impotency. This is definitely not how Munshi meant it to be. In order to have a greater universal appeal, and fetch more awards, Ray killed the very patriotic soul of the story.”

I’m not sure that there is such a difference, notwithstanding the “personal valor” which Premchand might have wanted to bestow on the two noblemen, reduced to “impotency” by Satyajit Ray. Did making them kill each other show their valour more than having them fight, and after having reconciled, start to play once again? I wouldn’t say they are cowards; they are simply ignorant of reality. They are never faced with a decision which could have, if taken, saved the fate of India. Ray points out on the contrary that it is too late, that India in 1856 was doomed. 1857 was at hand, and even if a battle (and its uncertainties) had to be won by the British, in retrospect, this date marked only one thing: India’s subjection. On the other hand, Ray also shows that the culture which Mir and Mirza stand for, and which the King promoted, was exquisite and elaborate, and this isn’t downplayed by the film. Certainly he is saying that today’s culture might gain from revisiting the sources which King Walid revived. Globalization represents a threat which can be fought against. And if some believe that, like the fate of the Indian empire in the movie, Indian culture is equally doomed to be eaten up by the global trends, they may be right, but that history has still to be written.

One last remark, concerning the cinematographic pleasure experienced in Shatranj ke Khilari: the game metaphor is an apt one for any movie, where actors move on the board as directed by the master; but the depth and intelligence of the game also receives added brilliancy from the contrast of scenes, inside and outside, the close-ups and the wide-angle shots, the rich and colourful evocations of a luxury where time seemed to have stopped. In short, the film is a song, a swan-song maybe, filled with tedium perhaps, but the song whose variegated accents – now grave, now joyful, ominous or ludicrous, mingle to recreate a world of refinement and beauty, eternal in its fleetingness.

For other reviews, do not miss upperstall.com who puts the movie in a perhaps more decadent perspective than the one upheld here. But his commentaries of some of the scenes are a real pleasure. On satyajitray.org there is the remark that the film was made during the “Emergency” period of Indian Politics, and he suggestion that Indira Gandhi acted in a similar way to that of Mir and Mirza. Minai has a rather pleasant take on the film, and Rameshram's comments make an interesting counterpoint! And at culturecartel.com John Nesbit holds the view that the film suffers from “excessive narration and overly staged acting”, so it’s interesting to read their point of view in the perspective of Ray’s “wonderful canon”. Finally, this page has some interesting things on Wajid Ali Shah and Ray's treatment of the historic figure.

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)