Teesri kasam, melancholic delight!

Publié le 2 Décembre 2008

The critical fame of Teesri Kasam, the 1966 film by Basu Bhattacharya, starring Raj Kapoor and Waheeda Rehman, is absolutely justified; it’s a tale of love and sadness, of beauty and melancholy; it enchants you, it pulls you along, it arrests you: in short it’s a little jewel. The blend of simplicity, poignancy and musicality is unparalleled, I think. It has a charm only equalled by the best Indian movies, such as Shri 420.

The story is rather simple: Hiraman, a cart-driver who is involved in black-marketing is almost caught by the police, and, upon escaping, vows he’ll never trade smuggled goods any more. He then reverts to bamboo trafficking, but that’s also a failure, and similarly he vows not to deal with it: what will be his third vow (teesri kasam)? We learn about it as he sets off on a journey, loaded this time with a rightful cargo, even if the lawfulness of this consignment will have to be reconsidered along the way, and will in effect lead to that fateful third vow.

But for the moment, he leaves his village, and we are left to wonder who it is exactly that he is transporting (we have been granted nothing but a calf climbing in the carriage, whose curtains are drawn). The slight suspense enables us to follow the driver (an already middling Raj Kapoor, very convincing nevertheless) through villages and woods, as night sets on and serves to highlight his rusticity. It isn’t until the morning that we catch a glimpse of his charge, the “fairy” Hirabai (as he calls her) who immediately casts a spell on him. They exchange names, and are surprised to see them similar-sounding (Hira means diamond, as Philip points out, and indeed they are both gems in their own way). So they become meetas, dear friends, as a result. She discovers his straightforward nature, his joyfulness (he’s always singing), and he is fascinated by her accomplishments: not only can she sing too, but she knows scriptures, and her face “looks absolutely…”

At the fair, she would have liked to stay with him, but they soon have to go separate ways, he with his fellow carting friends, and she with the troupe who has arrived in town, ready for the next day’s “nautanki”, or traditional show, in which she is the main dancer. Hiraman is filled with the importance of having had her attention and more perhaps, and brags about it among his pals. There’s lots of nicely felt companionship here. Soon she calls him in her tent, and asks him to stay for the few days of the fair, in spite of his strict sister-in-law’s advice. “Just be quiet, says Hirabai, she won’t know of it”: and he buys his fellow admirers’ silence with the passes she gives him to attend the shows.

Soon nevertheless, trouble is at hand: Hiraman has to face a first disillusionment; his beloved Hirabai is slandered in public, called a prostitute, and he causes a scandal by fighting with the impudent slanderer during a show. We understand she has trapped herself, by hiding her identity. She’s stuck in a “goddess” persona: he just thinks too high of her! The second problem is even more serious: the local thakur (zamindar) comes to the show and decides to buy her for one night. But she refuses, filled as she is with her new love for her “guru”. This will be her downfall, alas, because the lustful landowner has far more power than Hiraman: if she says no to him, the worst consequences will fall on her clan. The scene where she is surrounded by all her family, young and old, is really terrible, for she is given all the zamindar’s reasons through their mouths. She has to give in, and relinquish her poet and friend. Love is not for her in this world.

The songs of the movie perfectly match the action, in a way that only movies of that era knew how to, it seems to me. They is always a profound justification for them, they always comment upon the action in a true and meaningful way. More about this in a minute. Here is an excellent paragraph written by Upperstall about the musical dimension of Teesri Kasam:

Rarely does one see a film where music is so well integrated into the film. Shankar-Jaikishen have given an outstanding musical score in the film - simple melodies rooted in folk music. The music is much enhanced with the use of flutes, traditional string and percussion instruments. Sajanre Jhoot Mat Bolo, Sajanwa Bairi Ho Gaye Hamar, Duniya Bananewale all rendered by Mukesh and Pan Khaye Saiyan Humaro sung by Asha Bhosle stand out. It is interesting to see that in keeping with the realistic and human look of the film, Hiraman is just one of the revellers in the song Chalat Musafir and not the lead singer as is the case normally in our films.

Also delicate and bristling with life is the realistic filming: the lake water lapping the grass-studded banks, the undercover of branches as the cart moves away in the distance, the dusty roads filled with peasants of – it seemed – age-old Indian countryside, and the feeling of community shared by everyone. The photography is a treat too, viz those tricks with the lighting, which have been put to the best of their symbolical value: the oil-lamp inside the night confinement of the cart, lending its shadows to Hirabai’s thoughts; the backlighting when Hiraman crosses the village with the drunkard on the roof; and most magical of all, the sun-specked canvas behind Hirabai’s lovely head, imbedding it with sparkling diamonds as she smiles and listens to her friend the cart-driver.

But let’s now come to the core of the movie: why does Hirabai fall in love with Hiraman? Everything derives from there. Falling in love with her isn’t an issue, it must happen every minute, one would say. But the action of the movie is determined by her falling in love. The reasons usually given for Hirabai’s attraction towards Hiraman are “his innocence and simplicity” (Upperstall's review), or that “she is charmed by her driver’s blend of shyness, humility, and impassioned opinions” (Philip's fil-ums). PPCC declares that “Hiraman's naïveté and good nature charms Hira Bai”. All this is true, up to a certain extent, but I would like to indicate a more important reason, which has something to do with the meaning of the film, and will introduce its interpretation. Because the movie is not just a charmingly sad fable: it contains a message on attraction and destiny, even if it is perhaps banal, but the way it is blended with the story certainly isn’t.

What, indeed, happens during that cart-trip? True, the two discover the other one’s personality: Hiraman is refreshingly direct and simple; and the lady is a marvel of attention and delicacy. But the important is elsewhere: During the ride, Hirabai is reading her role for the next day, and the way she is shown pausing at the words indicates they have a special significance for her:

“There’s no one my own in this whole world; when separation is written in my destiny, why should I blame you?

There’s no one my own in this whole world, neither in my garden nor outside it…”

These words trigger a song on Hiraman’s lips, which she comes out to listen, musing deeply:

“My lover has become a foe, my deeds have become my enemies

If it is a letter, one can read it easily, but no one can read destiny.”

The way the young woman listens to these words indicates that she is listening to something else than just a song: she sees meaning in them, a meaning which clearly refers to herself.

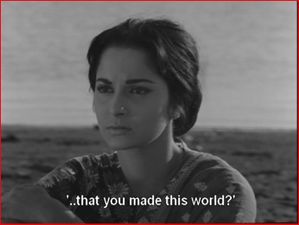

A little later, they stop near the river, and Hiraman, singing, tells her Mahua Ghatwaran’s story, a beautiful virgin “who looked just like a fairy” (like Hirabai had appeared to him at first), and who had an unhappy life - “no one to call her own in the whole world” says the story-teller. She had fallen in love with a thirsty traveller, but her step-mother refused that union, and sold her to a trader: the pair was broken. The melancholy song is built along these questions:

“O maker of this world, what came into your mind, that you made this world?

Why have you made this play called life?”

You created love, and told us to live,

You made us to meet friends on the path of life

And awakened dreams…

After awakening dreams, why did you give us separation?”

After this song, Hirabai announces to her fellow-traveller that he’s her teacher, her guru. From him she has learnt a secret, and this secret is contained in the song she’s just heard. We understand Hiraman is now a sort of prophet for her, a sort of visionary; he has sung about her and her sad destiny, and has transmuted her intimate drama and longing into a song, a thing of beauty. He has taught her the words to express her interrogations and her desires. He has perhaps even lifted the guilt she was feeling about her profession, and turned it into an existential Question asked to the Creator. So there is the reason for the feeling of gratitude and wonder that overcomes her, as she sits next to her meeta: he’s worded her pain and desire, he’s reordered it within the wider perspective of the cosmos; he’s deflected that suffering thanks to his story, and included himself in it: because naturally, he has become the traveller, and she is now that young virgin girl who was prevented from living with her true love. Her new love is a passionate desire to start anew life’s journey, to protect and cherish the awakener of her dreams, and live next to him far from the defiling brutality of her profession’s beastly side.

In Teesri Kasam, there is a belief in the power of poetry and music to transform life and purify it: Hirabai’s bath or cleansing (at the riverside scene) is symbolical of her desire to be renewed and reborn thanks to love and purity. Yet as she sings Hiraman’s song, we cannot but wander at the words too: they speak of a separation, of a destiny that cannot be changed. Even if it might be a consolation to know that God is the one answerable for our fate, and not us, still fate is fate, and the freedom to change it will not be granted. Hiraman has been singing to her like the Greek Chorus, foreseeing things which have not yet happened, but which in their unchangeable logic belong to the necessity of fatality. The transformation which Hirabai dreams of is doomed to remain a dream, and that wistful reality is one of the film’s magical charms.

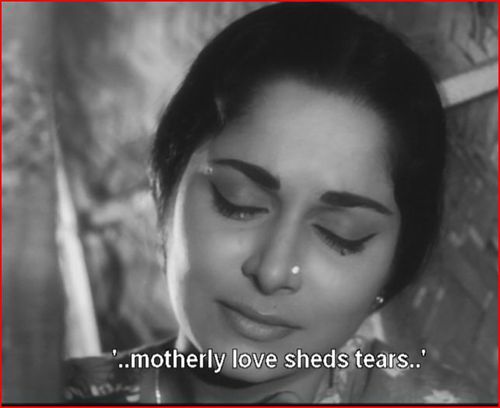

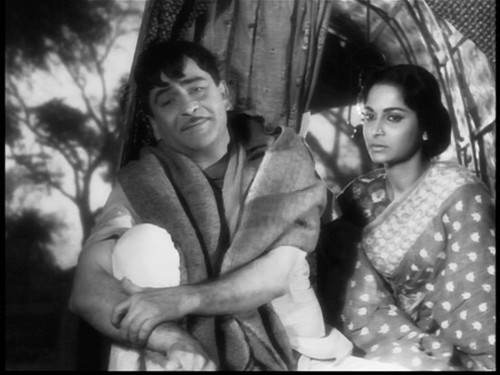

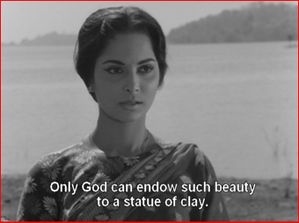

Waheeda Rehman’s beauty has never been more stupendous and breathtaking than it is here. Her striking softness, her incredible grace and tenderness, the perfect mould of her face makes watching her a sort of ecstasy. The way her caressing eyes look at Raj Kapoor, how she smiles at him, and searches his face for a confirmation of her love is like a baptism: she has been purified and awakened, as the song says, and her face radiates the morning sun, its warmth, its security. It’s almost embarrassing to watch her so much in love, so attentive and happy. The smiles the smiles, the eyes she shuts, the chin she lifts: all reveal so much more than what an ordinary actress might do, it’s amazing. I think she and Guru Dutt had been life companions (he committed suicide in 1964): well it’s a good thing he didn’t see her in this film: jealousy would have killed him again! I cannot thank enough Indian cinema for stopping actors and actresses from throwing themselves into one another’s arms. The kind of distilled eroticism that exudes from the couple’s calculated closeness is worth a hundred embraces. And B&W suits her perfectly too, it brings out the contrast of her dark hair and eyebrows in a way colour movies have forgotten all about (e.g. in Guide, a year before).

Raj Kapoor as has been said pleases the eyes, even if his latter-year chubbiness is showing a lot. Somebody has suggested on Bollywhat (link) that he was a miscast, being that old already. But he isn’t supposed to be a young man; and what we have said about the importance of Hirabai’s recognition of him as her guru makes him on the contrary a very good choice. We still enjoy that highly expressive face, his wide range of emotions, joyfulness, shame, fear, anger, as well as his pensive moments when he is beaten by events too great for him. His perpetual “Iss” is a great invention; I don’t know if it is a local word (probably for “come on!”), but it touches our hearts with its sincere-sounding simplicity.

All in all, Teesri Kasam is a delightful tale, full of many little and big treasures. It charms thanks to its original sadness, thus going against the facile shift of happy endings, and remains in the memory all the more.

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)