Their hands can see: Sparsh

Publié le 2 Février 2012

In the Mahābhārata, Gandhari voluntarily blindfolded herself throughout her married life. Her husband Dhritarashtra was born blind, and on meeting him and realizing this, she decided to protest silently by blindfolding herself. (source: Wikipedia – Jatland.com has a slightly different version “she decided to deny herself the pleasure of sight that her husband could never relish.”) Another website says that her protest was in keeping with her devotion to her husband, and as a result “she was hailed as a Sati for her sacrifice”.

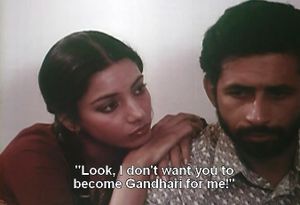

In Sai Paranjpe’s movie, Sparsh (Touch, 1980), the character played by Shabana Azmi, Kavita, similarly becomes engaged to a blind headmaster (Naseeruddin Shah), and because she seems too devoted to him, gets called by that name. This puts the movie in the context of the movements for woman’s emancipation, but with a twist, since in the sacrifice of Sati, the widow who joins her husband on the funeral pyre obviously doesn’t remarry. In Sparsh, not only is the context a remarriage, but Anirudh, the blind headmaster of an institution for blind children, warns Kavita against turning into a new Gandhari. He wants no such devotional sacrifice. And yet, this denial doesn’t seem to carry the weight of the film’s message: clearly Kavita’s sacrificial attitude is justified by the director. So could it be that Sparsh is more traditional than what it seems at first sight?

Several first-rate reviews of this little jewel exist on the web: for Carla the film, in spite of its slight defects, is sweet and touching, whereas Banno is more attentive to the educational dimension and A2line declares her enthusiasm at Naseeruddin’s acting skill. You can go and read the story first if you haven’t seen the film. But I’ll still have to say a few things about it, because some of its minor events carry an important significance. And we’ll come back to Gandhari bye and bye. You probably know that the drama at the centre of the story is Anirudh’s decision to break the engagement that he had started with the demure Kavita: having met by accident, the two notice each other at a party, and the teacher asks her if she might come and join the team of child-minders in his Institution. After some hesitation, the young widow decides to join, and quickly becomes very successful, both with the children and the staff. Until then lost in a withdrawn, nostalgic past, she finds a new present, and the promise of an undreamt-of future.

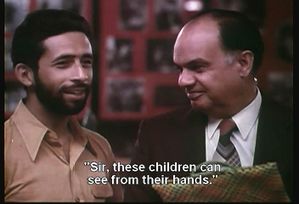

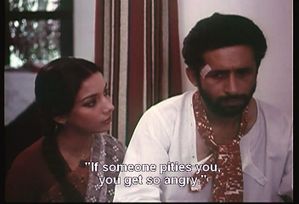

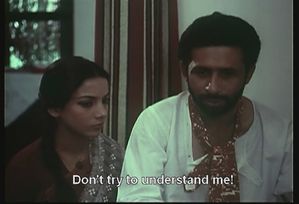

Even if Anirudh is a proud, demanding person, she senses this must hide a soft spot and soon enough she finds it. It means accepting a reorganisation of her values, first: she mustn’t consider the children or anyone at the Institution as “poor souls”, or handicapped victims, but as persons who need some help. No compassion please. Anirudh explains:

She is very much in need of involvement, and soon the pleasure and life-lines coming from the children win her over. Her personality blooms, and quite naturally she becomes closer to the man responsible for this. Anirudh cannot refrain from noticing her engaging character, her natural and warm nature. The way their budding attraction for one other is filmed makes it very interesting to watch, because one constantly wonders about the unusualness of the match. Everything seems to be going perfectly at first, and then little hitches occur, triggered by remarks overheard by the blind man. Kavita’s a real goddess, she’s sacrificing herself for him, how lucky for him, she will be able to do everything he can’t… Unwittingly, she’s rubbing in what he’s been trying to evade all his adult life: dependence and pity.

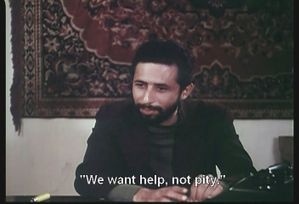

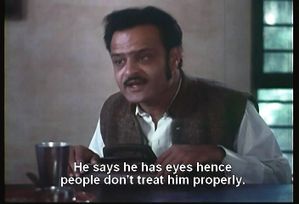

And that’s where he balks. Pity: for him pity is an attitude he will not harbour; pity makes him feel how much he’s been fighting against himself to be self-reliant and grown. If other people feel pity for him, the conclusion is that he’s not been successful in projecting an autonomous persona for himself. If people pity him, then he’s still the child he suffered to be all those years. Pity means inferiority, inadequacy and failure. How dare these people feel pity for him who has, so much more than able people, fought successfully to the top and reached the position of headmaster of an educational institution?

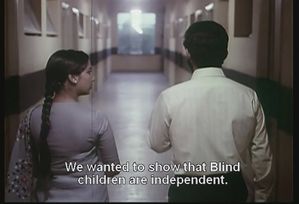

Anirudh’s refusal of pity and sympathy shows he doesn’t see the reasons why others might pity him, and also indicates how far he still is from real independence. He doesn’t see that love contains pity, essentially. Love needs to give itself, to pour itself on wounds and complete what is incomplete. Love is so soul-searching that it can accept to maim itself in order to be accepted and loved in return. This is what happens to little Paplu: this young boy, who isn’t blind, is a pupil at the Institution and helps his blind friends to read. He therefore has an advantage which he sometimes uses for his personal ends. But when Kavita comes to the school, and makes the blind children less dependent, he’s less used, and less loved, and this is what his father comes to the headmaster to complain about:

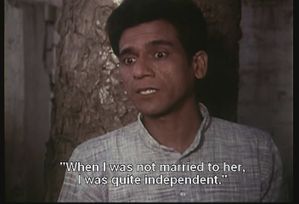

And as a result we have the very funny and touching story of the lovely princess in her devilish Castle who one day sees her Prince rush in with his Chariot and fly to her rescue. Such is the power of love that it provokes sacrifice, because it contains it. Loving means sacrificing one’s ego on the altar of the beloved. But if this ego isn’t yet built, how can one sacrifice it? It becomes suicide. Anirudh has a colleague, Dubey (played by a young Om Puri), whose wife is ill, then dies, and whose grief we witness:

When Anirudh puts together his growing feeling of unease because of Kavita’s insisting presence, (which he can’t understand as her attraction to himself), and Dubey’s realization that now he’s going to have to become independent again, as he had been before his marriage, something clicks inside his darkness: “she’s trying to “understand” me, she’s doing what I have set to do for myself, because nobody else can do it: make sense out of my suffering, find meaning in the pain and humiliation. She wants to educate me, I am a child once again”:

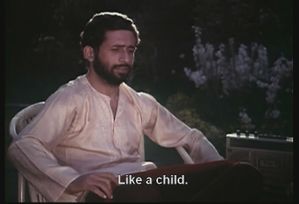

Anirudh’s drama is that he cannot “see” like a child sees, through love. He hasn’t yet reached the point where he can “change and become as little children” (Matthew 18,3). Indeed, such a change requires one to have gone through a process of abandonment; to reach this state where you can see the Others around you as divine images and become their child, so to speak, you must accept who you are, you must even forget who you are, forget your indulging quest for yourself, and extract yourself from yourself. He hasn’t yet suffered enough, perhaps, or conversely, he has suffered too much and isn’t healed yet. He cannot see that Kavita’s love is this healing. He believes he can heal himself on his own, through his own efforts. Conversion is precisely that: accept to be healed by another. “Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.” Healing comes when one recognises that efforts alone, no matter how in earnest, cannot save us.

Now Kavita too has suffered: but what makes the difference between the two of them? How come she’s the one who “sees”, whereas he’s “blind”? She’s also been shut up in herself, and has had to reconstruct a broken ego. Why can she love authentically, and not him? The answer is in the film’s title: Sparsh, touch. Kavita’s change (her conversion) has come about through a touch: she’s been touched, that’s how children have converted her and brought her to the school, where she’s sloughed off that old nostalgic self. We often see Kavita’s hands, they’re the physical and at the same time spiritual means which has saved her, and why she will be able to save Anirudh: she’ll touch him, and cure his sickness, she’ll finally be able do that miracle. (Well, in fact the last move will be operated through Manju, Kavita’s friend, but in essence, everything Kavita has done before has enabled Anirudh to finally open his ears to what Manju tells him, and let go of himself).

The theme of touching has been the subject of other “meditations” on this blog (Sujata, for example, or Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable). Blind people operate with hearing, smell and touch. Hearing is of course the primary sense for them, but touching is much developed too. What’s therefore surprising is that Anirudh’s sense of touch isn’t as sensitive as Kavita’s, who normally doesn’t need it so much and, according to the Darwinian law of need creating the function, shouldn’t have developed it all that much. One clue is the conversation which they have around the theme of darkness, at Kavita’s house one day. “Please leave me alone in my city of darkness”, says Anirudh, hurt because he cannot make her understand he isn’t ready for her love. “I too am living in the dark”, she answers. And then she suggests:

A beautiful passage indeed, which demonstrates Sai Paranjpe’s art as a writer, but which also explains the two different uses of touch exemplified by the two characters. Anirudh’s blindness has made him develop a certain sense of touch, of course, but he’s been blind to realities which have also stunted it. Kavita, on the other hand, has felt her way out of her darkness thanks to the light of love, and now she knows the way out. If only he’d let her, she could teach him how to feel his way out from the sombre pit of anger and self-pity. Anirudh is locked in the cave of his own making, and it’s all the more poignant as he’s so keenly in need of her touch:

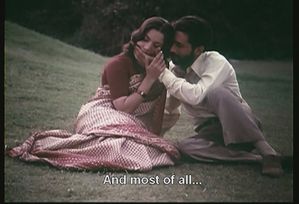

For me, the photo on the right shows a very distressing moment, when Anirudh tries to make the miracle happen. In the gospel, the divine healer also had put his hand on the blind man’s eyes, mixing it with dirt, and this had healed him. It seems here that Anirudh is trying to reproduce that moment, and wanting love to perform the same miracle. Out there on the lawn, in the famous scene when the pair evoke Kavita’s beauty, everything was so right: Anirudh had perfectly understood (= his blindness had wonderfully prepared him to understand) that real beauty belongs to the invisible realm of the person’s inner sanctum. Even if the film-maker makes us at that moment contemplate Shabana Azmi’s flamboyant physical beauty, even if the scene, as somebody says somewhere, is full of erotic magic, nevertheless it opens onto the silent world of touch, where we are all equal, all children of one Creator of velvety softness.

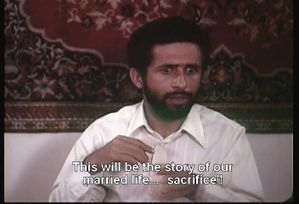

One last discovery in Sparsh: at one point, Kavita declares something which is misunderstood by Anirudh. For her “love isn’t everything in life”, and she explains that she has a “duty” to perform: she has remained too long pent-up in herself. Now is the time for opening up, doing something no longer for herself alone, but for “everybody”, as she puts it, and Anirudh is part of that plan. She will no longer think about herself anymore. But he sees that as nothing more than a sacrifice; in fact he has a simplistic understanding of sacrifice. He cannot perceive its transformative process, how it enables somebody to merge into a vast and infinite dimension. Kavita for him is only involved in a pact with herself. And so logically he refuses that. He refuses her to become Gandhari, who, according to the myth, was said to have had one hundred children! 100! I think the incredible record for a single woman is 68, astounding as it sounds. But one hundred, this figure clearly means that Kavita is going to love and nurture as many children as she can, she is going to multiply her attention to reach out and help as many as it takes. Perhaps Anirudh confusedly feels this “sacrifice” in fact sacrifices him!

To round off this long review, I just want to say that the two leads are excellent, perhaps Shabana Azmi even greater than Naseer, who pulls off a superb performance. We can actually see in him Anirudh the blind headmaster, and he’s very convincing. But Shabanaji, ah, she’s perfect, there a dedication, an effortlessness in her acting which distinguishes her as one of the magnificent actresses of her age. Her Kavita is a constant delight to watch and one falls in love with her promptly: anyway, she’s said it: she’s going to love everybody!

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)