Roja: how can we love and live apart?

Publié le 26 Juin 2009

Roja is an excellent little movie made by Mani Ratnam back in 1992, starring Arvind Swami and Madhoo (Raghunath); it was a real pleasure to watch another of Mani Ratnam’s works. His intelligence, his realism, his careful balance of private and public issues which are typical of his works, all this provides a cinematographic pleasure that makes you feel clever and informed.

This is the story: After an opening scene where soldiers, in the misty half-light of a mountainous forest, encircle and catch a man whom we later come to recognize as a Kashmiri separatist, the scene changes to the Indian countryside, full of splendour and worthy of Yann Arthus-Bertrand’s shots in his film “Home”. We then follow the arrival of an educated young man, Rishi Kumar, who comes to visit a family where he hopes to find a wife (he's no less than as a local hero - very funny and touching scenes of welcome). He wishes to marry a “village belle”, he says, even though he’s always lived in the city. But when he arrives in front of her, she has a secret: she cannot marry him, could he please choose another girl? But, guess what? Upon arriving in the village, the visitor had been spotted by the younger sister, Roja.

The spectator has already noticed her, this fiery, brown-eyed beauty, during the bucolic opening. And while the young man was coming, she had spied on him, they had exchanged looks (those knowing looks that lovers the world over recognize immediately, but know as well how to reject because of social realities). But when Rishi Kumar’s decision has to be made public, when they all ask him whether he’s made up his mind, he points to Roja: “she’s the one I want”. Of course this is a minor scandal, and for Roja most of all, but she doesn’t have the choice, and must marry the nice-looking stranger. During the wedding ceremonies and the song Rukmani rukmani which captures its joy and expresses its social meaning, Mani Ratnam uses a remarkable background: a rushing floodlit waterfall, symbol of the impetuousness of love perhaps, and makes old women dance with the young, in a vibrant celebration of life. But Roja leaves her home without her sister having explained the quandary she put her in. This is nevertheless only momentary, and the valiant little sister will soon have her heart filled beyond her dreams.

Then drama occurs; this newly found treasure of a hubbie is kidnapped, and taken into hiding; the horrid battle of waiting, hoping, doubting, despairing takes place, all too familiar in our modern world. Those who know Mani Ratnam know he’s capable of great and efficient suspense there. But I won’t tell you how the film’s story continues, only that it’s packed with action and feeling, against a backdrop of breathtaking natural beauty.

That is what the film will be, in fact, a magnificent celebration of beauty, life and love, in the best Bollywoodian tradition, the one that doesn’t base its appeal on the star-system. Of course it’s Mani Ratnam, so there’s the political purpose (see below), but first the film is simply a classic and perfect Bollywood production, with all the necessary and well-balanced, well seasoned ingredients: we have the intense love affair, the danger-filled and malevolent obstacles to love, the charming and witty humour, which comes from the situations themselves, and does not require a comedian’s antiques; the superb songs (AR Rahman, needless to say), which emerge from the intensity of the action, or the passion; and there are all the great emotions: generosity, hatred, courage, determination, indignation, resistance, pity, silent love, and the magical climax where the two lovers reunite and tears gush out.

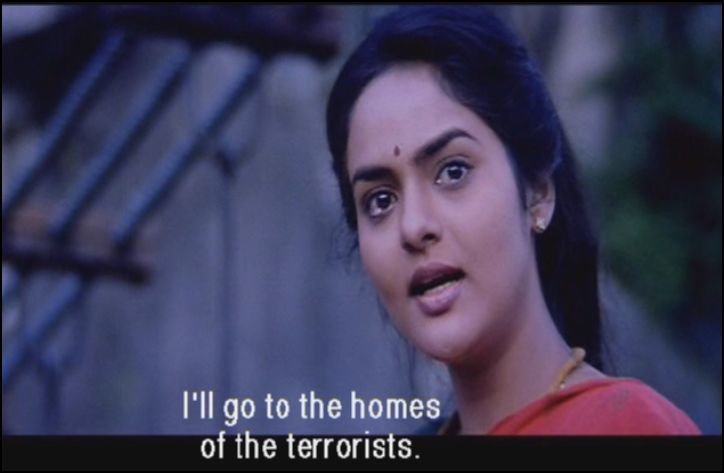

Madhoo/Roja is the soul of the movie: her willpower, fuelled by a love which never fails, her faith that Rishi Kumar, her adored husband, is alive in spite of all odds: these feelings are so poignantly presented that it works, we forget the little inconsistencies and the exaggerated story elements. She appears to have forgotten herself, and becomes the fighting wife, the astoundingly daring lover, whose youth serves as experience and aplomb. Her self-confidence sweeps aside, not only all resistance, but all disbelief that we are watching a movie. We are absorbed in the anguish of her quest, in the fearlessness of her pursuit, and we fear with her, we hope with her, we cry with her. Such is the strength of acting!

Arvind Swami’s character and personality touches also, because of his restraint and solidity. He doesn’t emote a lot, perhaps, but I found I liked his acting, which is at times almost expressionless: this lack of intensity struck me in fact as a kind of strength, and the sign of a maturity which complements Roja’s youthful and domineering character. Reviews on Imdb have noted the patriotism of the scene where beaten and humiliated, Rishi Kumar manages to repeat his “jai hind” to the face of the separatists, knowing full well he will incur the consequence of their rage, and one of the movie’s weaknesses is apparent there, in this vibrant and somewhat naïve nationalism. But then again, perhaps this is a westerner’s view. Or it’s because the film was done back in 1992, when certain illusions about the resolution of the Kashmir conflict could still be nurtured.

So: what is Roja, then? A brilliantly made entertainer? A political movie using the swallow-down virtue of boy meets girl? If we notice the two aspects deal with separation and reunion, perhaps we could call it a hymn rooted in the love of the land: its overall purpose is the refusal of separation, and the assertion that love must and will reunite those who are separated. Separatists are wrong, violent, and counter-nature. Roja fights for reunification with her husband, just as Mani Ratnam films for Kashmir to remain united to India. Two reunifications, and this, even if Roja is repeatedly criticised in the film for her naïve and selfish intentions: doesn’t she know, the general tells her, that the exchange of her husband against the terrorist Wasim Khan has cost the lives of many soldiers, who were certainly husbands and fathers too? How dare she demand her husband to be exchanged, when so many mothers and wives have silently accepted their sacrifices? But the fact that the minister accepts her request shows that these two apparently antagonistic realities can combine, and that unification should be also inspired by human values such as love, and not only through the hard facts of negotiation and politics.

One last word from imdb reviewer Reachrajdream, who I think has a good point: This movie is inspired from Italian movie De Sica's I Girasoli (1970), neverthless no complaints because I don't believe in originality. The movie is worth watching because of good story and flow of the story. (…) Even Vittoria De Sica might have been happy watching this movie because such a solid, positive enhancement of his work

/image%2F1489169%2F20200220%2Fob_9722d6_banner-11.JPG)